DETROIT — Can an exhibition be informed by the place it visits? 30 Americans, a survey of works by African American artists in the Rubell Family Collection, which debuted in Miami, and has since visited places including the Milwaukee Art Museum, stands on its own as a remarkable assortment of contemporary voices — but in the context of Detroit and the Detroit Institute of Arts, these voices take on a whole new tenor. Though some have been critical of the collector-driven nature of the show, the Detroit Institute of Arts devoted substantial time and resources to researching the exhibit, in terms of its impact, interpretation, and reception among Detroiters, conducting focus groups with the interest of making the material accessible to museumgoers.

I happened to be a member of one such focus group, and some of the commentary and questions posed by participants regarding their comfort level with racially-charged (or just racially-focused) subject matter offered an eye-opening glimpse into the DIA’s struggle to expand perspectives and conversations in a city that has remained deeply divided along racial lines. Detroit is the city with the largest majority black population in the country, and it is significant to see a recent effort on the part of arts organizations to diversify their programming in a way that reflects these demographics. By the standards of the surrounding Metro Detroit communities, the work shown in 30 Americans is controversial.Kara Walker is a household name in most urban art centers; the DIA acquired one of her pieces in 1996 since 1996, but has never put it on public display. The piece itself is comparatively tame with respect to “Camptown Ladies,” which dominates two entire walls at the heart of 30 Americans.

This queasiness in dealing with some of the harsher realities of historic (and contemporary) race relations in the region has lately been addressed with projects like Nick Cave’s much-lauded citywide happening “Here Hear” sponsored by Cranbrook Art Museum (Cave is also one of the artists represented within 30 Americans). But while Cave’s work can be construed as whimsical despite its serious conceptual underpinnings, 30 Americans really tackles some of the hardest aspects of the brutal legacy of slavery in our country, and the suppression of the African American voice, in myriad forms.

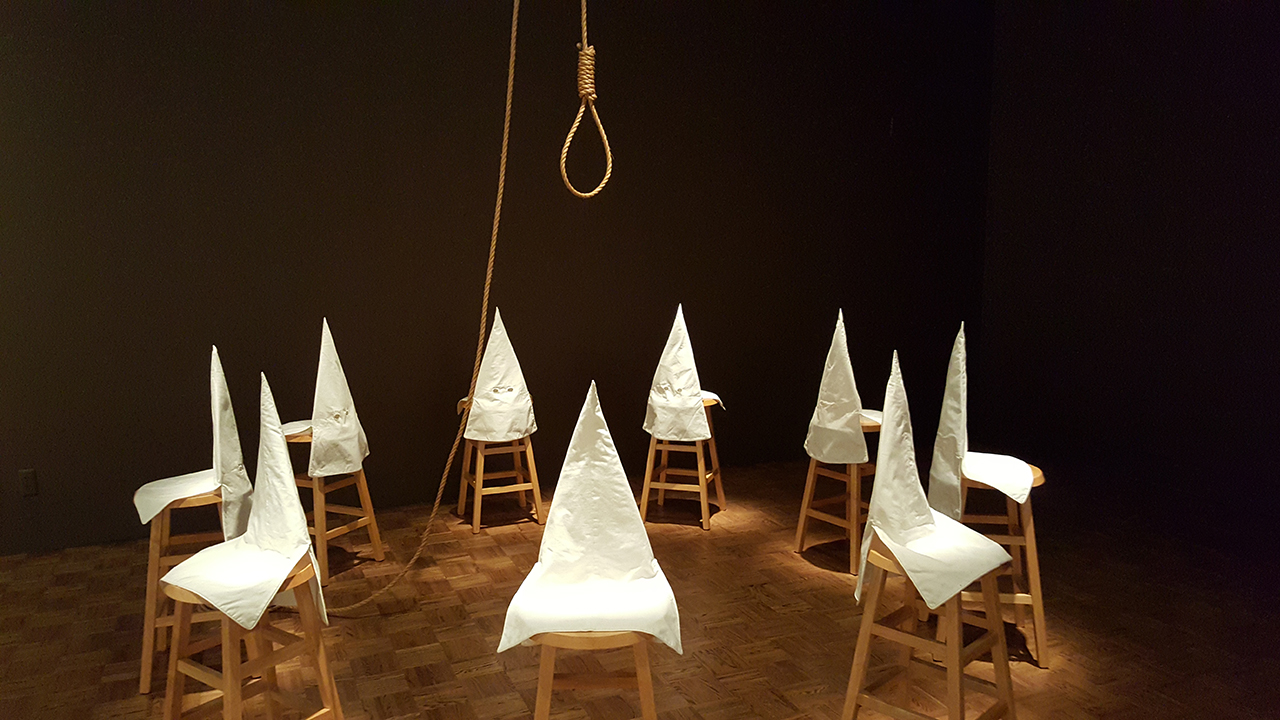

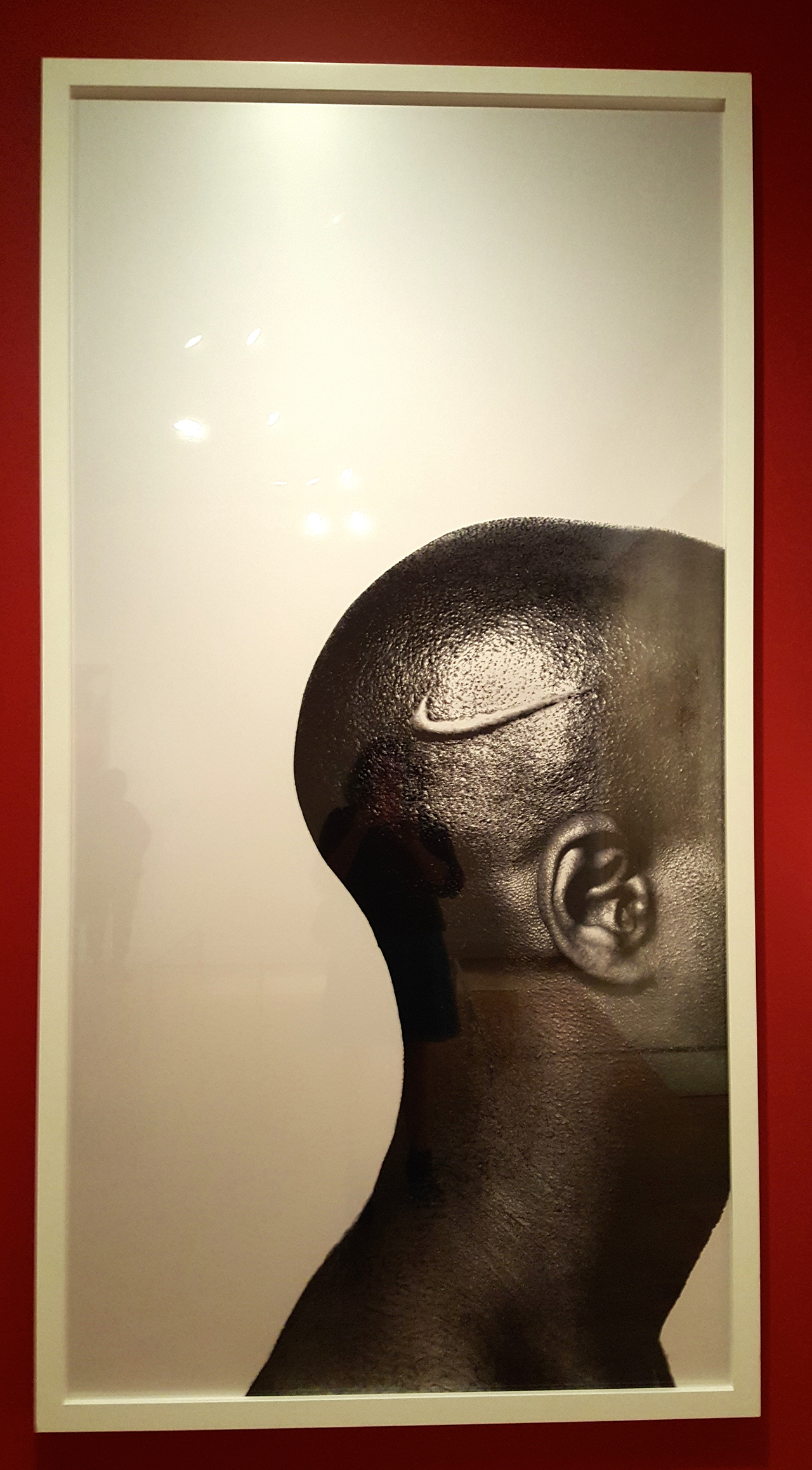

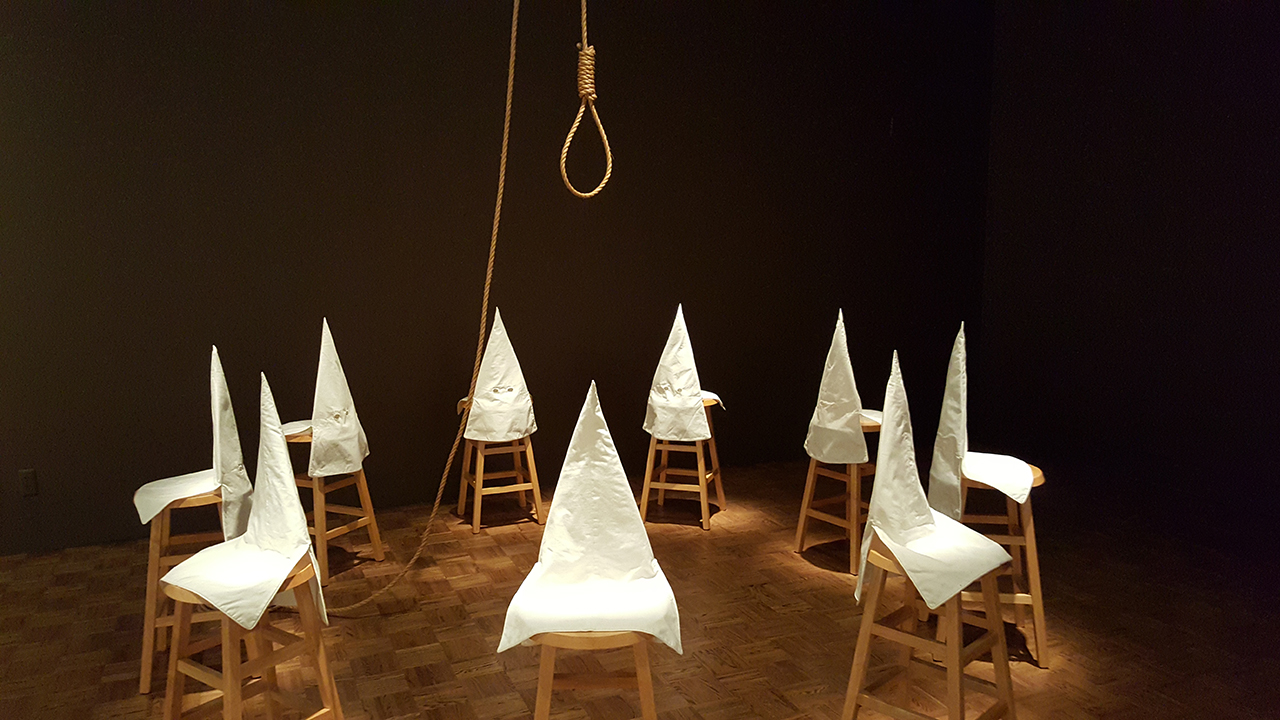

Works in 30 Americans include “Duck, Duck, Noose,” (1992) by Gary Simmons — where the children’s game is transformed into a circle of chairs topped with Klan hoods, the eponymous noose awaiting whoever ends up in the middle; “The Great White Way, 22 Miles, 9 Years, 1 Street” (2001–2002), a digital video process piece and statement on homelessness wherein artist William Pope.L, wearing a Superman costume, dragged himself on his stomach down the full length of Manhattan, incrementally over the course of nine years; and “Branded Head” (2003) by Hank Willis Thomas, which showcases the Nike swoosh — a symbol tied inextricably to the racially loaded world of professional sports — that both literally and figuratively brands the head of an unidentified black male subject. From a bundle of suspended feathers and clothing bearing Tupac’s face, as though hung upside-down, to a towering wall of cotton bales, 30 Americans is not pulling any punches, and in hosting this challenging assortment of works, the DIA is demonstrating a heretofore unseen level of willingness to bring these issues to light among the Detroit Metro populace.

More normative perspectives are also present in 30 Americans — as the show’s title would suggest, the point is not necessarily to emphasize the other-ness of African American people, but their identity as Americans. In terms of connecting with its immediate community, this may be the first time the DIA has featured a show wherein the racial demographics of the depicted subjects more or less accurately reflect the racial demographics of the city. Who you see on the walls sends a powerful message about who is welcome in the galleries, and 30 Americans stands as a clear appeal on the part of the DIA to court its city population as a desired base of attendance. This effort was reinforced by the opening night community celebration, which featured playful local touches like Faygo pop and a performance by rising local star Tunde Olanrian, whose dramatic showmanship and inspirational musical message have him poised to break atmosphere and take the country by storm (presumably accompanied, as always, by his two synchronized and utterly deadpan female backup dancers).

Was the DIA’s handling and interpretive treatment of 30 Americans executed flawlessly? It received mixed reviews, but to lambast the museum’s intentions — as did Tyler Green, in a series of tweets focused on the politics of allowing collectors such a large role in presenting works they own — is to miss the intended audience of 30 Americans, Detroiters who have never before set foot in the DIA. The loudest critics of the DIA’s exhibition design were, in the end, perhaps not those for whom it was intended.

Exhibitions like 30 Americans could have the potential to amplify conversations about race within Detroit, while helping to demonstrate a meeting between its communities and one of its longstanding institutions, and to write off that effort as a shell game on the part of the Rubells or a misstep by the DIA is giving it short shrift. Detroit is not the only city that has hosted 30 Americans, but it could be one of the most important.

30 Americans continues at the Detroit Institute of Arts (5200 Woodward Ave, Detroit) through January 18.