By Richard Reep

Published: February 27, 2013

African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond

Mennello Museum of American Art

900 E. Princeton St.

407-246-4278

mennellomuseum.com

$4

Unlike its big sister across the Loch Haven lawn, the Mennello Museum of American Art is no uptight white box. Its richly hued walls and galleries shine warmly in sunlight and are the perfect place for the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s touring exhibit Harlem Renaissance. One of seven venues nationwide chosen to host this show, the Mennello has this African-American art during Black History Month, and it will shake you to the core as you drink in the American experience through black artists’ eyes.

Superbly curated by the Smithsonian’s Virginia Mecklenburg, the exhibit presents about three dozen artists working in all types of media. Themed groupings in four galleries pulse with the sublime, the protest, the joyous and the ethereal, all commingling to reveal black spirituality and struggle.

John Scott’s “Thornbush Blues Totem,” an 8-foot-tall, brightly colored metal sculpture practically radiating jazz music, greets visitors at the entry. Resembling blues bands at different angles, the sculpture beckons the viewer inside. Once past it, however, Thornton Dial’s “Top of the Line (Steel)” halts the viewer in his tracks. Dial’s political work, inspired by the 1992 Los Angeles race riots, confronts the viewer with savage black-and-white brushwork, ropes, angry faces and chaotic power. If art, as Dial says, is for understanding, this piece cannot fail to impart the point of view of the street.

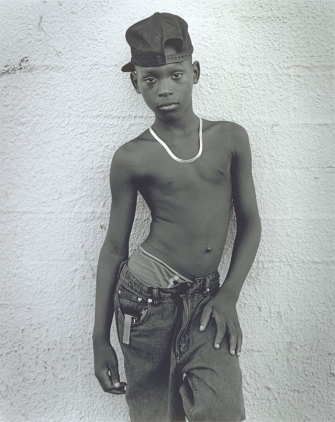

In dim, church-like light, the far right gallery offers photography, painting, sculpture and installation. Masters like Gordon Parks, Roy DeCarava and Earlie Hudnall Jr. make equality happen. Photography gives souls and lives and personal character to people otherwise invisible to mainstream art in the 1930s and onward; here they work, play and shine with dignity. Hudnall’s “Lady in Black Hat With Feathers” is so incredible – the subject’s hat, face and dress blend monolithically into a single sculpted form of beauty and strength. His “Miss Bow From Laurel” is even more electrifying; Miss Bow’s profiled face and hands tell of labor and toughness we can only imagine.

Most haunting in this gallery is “The Colonel’s Cabinet,” by Renee Stout. This curio cabinet filled with Native American and African artifacts collected from the world travels of fictitious black character Col. Frank reveals a desperate attempt to discover lost identity, using the favorite method of white world travelers who display souvenirs in their homes (probably dusted by black housekeepers).

In the front right gallery, several large pieces are grouped, and some hint at the contradictory status of the African in America. In William H. Johnson’s two paintings about farm life, look for subversive symbols suggesting dreams of revolt within the bright scenes. Frederick Brown’s “John Henry” is more overt, fast-forwarding the mythic, unsmiling, vaguely hostile John Henry into a modern steelworker’s union. Here, bleak subject matter interweaves with bright surfaces in masterful hands.

In the far left gallery, abstract expressionist artists challenge viewers’ perceptions of color and light. Emilio Cruz’s “Angola’s Dreams Grasp Fingertips” is a gigantic diamond mandala, with delicious, wiggling ropes of blue in a primal soup of magenta and yellow. Felrath Hines’ crisp, flat color fields contrast this with austere geometric patterns, yet have a jazz tempo to them. The abstracts explore powerful themes unrelated to race and struggle, yet are informed by their makers’ perspectives.

Black historian W.E.B. DuBois cautioned that “herein lie buried many things” about the African-American experience, and his statement is true of this exhibit as well. This is art at its best, a means to communicate, document and especially transmit understanding. This show, as deeply powerful a communication vehicle as any, does not hold back. Uncover what lies buried here and emerge stronger, having tasted a rich cocktail of beauty, pain and sorrow; you’ll never be the same again.