TENAFLY, N.J. — You can count the number of American public museums devoted entirely to African art on a few fingers.

Enlarge This Image

Ruby Washington/The New York Times

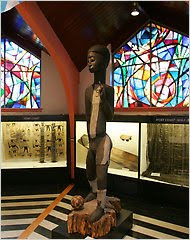

An installation view at the African Art Museum of the SMA Fathers, in Tenafly, N.J., showing a 10-foot-high carved figure of Salif Keita, the 1960s Malian soccer hero.

Blog

ArtsBeat

The latest on the arts, coverage of live events, critical reviews, multimedia extravaganzas and much more. Join the discussion.

More Arts News

Enlarge This Image

Ruby Washington/The New York Times

A Yoruba dance mask, with a mini-zoo on top, from Nigeria.

There’s the National Museum of African Art in Washington. And the Museum for African Art in New York, reopening in a new Fifth Avenue home next spring. And there’s a third you’ve probably never heard of, the African Art Museum of the SMA Fathers here.

This museum is small and unorthodox in its setting: a stained-glass-windowed hall attached to a Roman Catholic church. But it’s the real African deal, with a collection covering the continent, top to bottom, coast to coast, old to new.

If you’re in New York City, you’ll have to cross the George Washington Bridge to find it. But if you’re looking for visual magic — a Yoruba dance mask with a mini-zoo on top; a brocaded body-wrap from Ivory Coast that seems to float on air; or a 10-foot-high figure of the 1960s Malian soccer hero Salif Keita dressed in team colors and cut from a single tree — you’ll have come to the right place.

And a pretty place it is, the leafy residential campus of a religious order called the Society of African Missions, but better known as the SMA Fathers, with the initials being the order’s name in Latin, Societatis Missionum ad Afros.

The order was founded in Lyon, France, in 1856 by Melchior de Marion Brésillac. A precocious young cleric, he was made a bishop at 29 and set up a network of missions in India before traveling to Africa to do the same. His time there was brief: six weeks after arriving, he died of yellow fever.

But his order was long-lived. It set down roots in present-day Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia and Tanzania and maintained headquarters in Europe and the United States. The Tenafly seminary, which opened in 1921, was intended as a training center for African-American clergy. The racial politics of the time thwarted that plan, but two decades later, after an infusion of immigrant Irish priests, Tenafly became the SMA’s American home base.

Part of the order’s mandate was to embrace and preserve indigenous cultures. Among other things, this entailed acquiring art wherever it was found in Africa but also commissioning African artists to create new pieces based on Christian themes. One priest, Father Kevin Carroll (1920-1993), an anthropologist and photographer, requisitioned such work from some of the most celebrated Yoruba sculptors of the day.

During a century and a half, the SMA amassed some 50,000 items and built museums to hold them: two in France and one each in Italy and the Netherlands. The Tenafly branch, installed in its present setting in 1980, is now incorporated as a nonprofit institution technically independent of the order and has its own modest holdings of around 1,000 objects. Some came through missionaries, but many were donated by a generous group of local private collectors who have also backed a series of strong thematic exhibitions during the tenure of the museum’s director, Robert J. Koenig.

These donations account for much of what’s in the current show, the first of two year-long permanent-collection displays. They are defined by geography, one of several artificial categories used to package African art for consumption, others being tribes and traditions. But when you have holdings of limited examples of many different kinds of things, what other presentation can you use?

Anyway, geographic delineation is quite approximate here: “Guinea Coast and the Sudan” is really Chad to South Africa. The exhibition labels avoid hard-and-fast alignment of peoples, places and styles. And overarching themes, when introduced, are lightly applied. On the whole this is a show about object-by-object variety.

There are plenty of so-called classic sculptural types. Dan masks from Liberia have Valentine-heart faces exquisite and inscrutable enough to make sense on the streets of Goldoni’s 18th-century Venice. Equally familiar and enchanting are helmet masks carved for Mende women’s societies in Sierra Leone: petite of feature, high of forehead, demure of expression, each an ideal of feminine beauty.

Dogon dance masks depicting birds, antelopes, rabbits and people are the exact opposite of demure. With their paint-freckled surfaces, fiber wigs and movable parts, they’re a chorus of cawing, braying, snuffling, singing beings, visual art as visual noise. You can imagine what they would have looked like on costumed performers in constant motion, twirling, dipping and raising dust.

Enlarge This Image

Ruby Washington/The New York Times

An installation view at the African Art Museum of the SMA Fathers, in Tenafly, N.J., showing a 10-foot-high carved figure of Salif Keita, the 1960s Malian soccer hero.

Blog

ArtsBeat

The latest on the arts, coverage of live events, critical reviews, multimedia extravaganzas and much more. Join the discussion.

More Arts News

Enlarge This Image

Ruby Washington/The New York Times

A Yoruba dance mask, with a mini-zoo on top, from Nigeria.

There’s the National Museum of African Art in Washington. And the Museum for African Art in New York, reopening in a new Fifth Avenue home next spring. And there’s a third you’ve probably never heard of, the African Art Museum of the SMA Fathers here.

This museum is small and unorthodox in its setting: a stained-glass-windowed hall attached to a Roman Catholic church. But it’s the real African deal, with a collection covering the continent, top to bottom, coast to coast, old to new.

If you’re in New York City, you’ll have to cross the George Washington Bridge to find it. But if you’re looking for visual magic — a Yoruba dance mask with a mini-zoo on top; a brocaded body-wrap from Ivory Coast that seems to float on air; or a 10-foot-high figure of the 1960s Malian soccer hero Salif Keita dressed in team colors and cut from a single tree — you’ll have come to the right place.

And a pretty place it is, the leafy residential campus of a religious order called the Society of African Missions, but better known as the SMA Fathers, with the initials being the order’s name in Latin, Societatis Missionum ad Afros.

The order was founded in Lyon, France, in 1856 by Melchior de Marion Brésillac. A precocious young cleric, he was made a bishop at 29 and set up a network of missions in India before traveling to Africa to do the same. His time there was brief: six weeks after arriving, he died of yellow fever.

But his order was long-lived. It set down roots in present-day Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia and Tanzania and maintained headquarters in Europe and the United States. The Tenafly seminary, which opened in 1921, was intended as a training center for African-American clergy. The racial politics of the time thwarted that plan, but two decades later, after an infusion of immigrant Irish priests, Tenafly became the SMA’s American home base.

Part of the order’s mandate was to embrace and preserve indigenous cultures. Among other things, this entailed acquiring art wherever it was found in Africa but also commissioning African artists to create new pieces based on Christian themes. One priest, Father Kevin Carroll (1920-1993), an anthropologist and photographer, requisitioned such work from some of the most celebrated Yoruba sculptors of the day.

During a century and a half, the SMA amassed some 50,000 items and built museums to hold them: two in France and one each in Italy and the Netherlands. The Tenafly branch, installed in its present setting in 1980, is now incorporated as a nonprofit institution technically independent of the order and has its own modest holdings of around 1,000 objects. Some came through missionaries, but many were donated by a generous group of local private collectors who have also backed a series of strong thematic exhibitions during the tenure of the museum’s director, Robert J. Koenig.

These donations account for much of what’s in the current show, the first of two year-long permanent-collection displays. They are defined by geography, one of several artificial categories used to package African art for consumption, others being tribes and traditions. But when you have holdings of limited examples of many different kinds of things, what other presentation can you use?

Anyway, geographic delineation is quite approximate here: “Guinea Coast and the Sudan” is really Chad to South Africa. The exhibition labels avoid hard-and-fast alignment of peoples, places and styles. And overarching themes, when introduced, are lightly applied. On the whole this is a show about object-by-object variety.

There are plenty of so-called classic sculptural types. Dan masks from Liberia have Valentine-heart faces exquisite and inscrutable enough to make sense on the streets of Goldoni’s 18th-century Venice. Equally familiar and enchanting are helmet masks carved for Mende women’s societies in Sierra Leone: petite of feature, high of forehead, demure of expression, each an ideal of feminine beauty.

Dogon dance masks depicting birds, antelopes, rabbits and people are the exact opposite of demure. With their paint-freckled surfaces, fiber wigs and movable parts, they’re a chorus of cawing, braying, snuffling, singing beings, visual art as visual noise. You can imagine what they would have looked like on costumed performers in constant motion, twirling, dipping and raising dust.