Barkley L. Hendricks remembers when he and other fellow artists, all prize- winning graduates of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, were hanging their paintings for the school’s final exhibition.

A professor at the school approached Hendricks’ work. “This is certainly a black wall,” the teacher told Hendricks. “Don’t you ever paint portraits of white people?”

Barkley is black.

The incident happened more than 20 years ago, but Hendricks contends that black artists continue to be victims of racism.

“It is one of the reasons that I left Philadelphia,” says Hendricks, who now lives in New London, Conn., where he paints and teaches art at Connecticut

College. “You find that this ignorance toward black artists continues in the galleries.”

Hendricks is one of many black artists who say they are discriminated against professionally because of their race. However, other minority artists contend they have never encountered racial prejudice in galleries; they say the role race plays in their art work has been overblown.

“Good art is good art,” notes Barbara Beatty, 48, a free-lance illustrator who paints landscapes with no black images and says she has encountered no prejudice from Philadelphia galleries. “A gallery owner looks at my slides and has no idea what color I am. This is simply not a problem.”

Ulrick Jean-Pierre, a Haitian artist who moved to Philadelphia 11 years ago, also contends gallery owners are colorblind. “They can relate to my work and its spiritual influences,” he says. “I can please myself and please everyone else.”

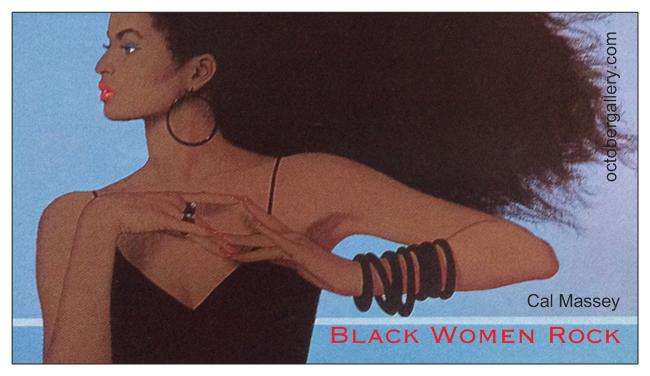

For others, the issue is not so simple. Cal Massey, a 63-year-old artist in Moorestown, N.J., who does portraits and drawings of black men and women, remembers when Art Expo – a huge annual exhibit of paintings and prints in New York – exhibited no black artists.

“No one thought they could sell black images,” says Massey. “No one thought blacks or whites would be interested . . . You have to blame galleries to a large degree for not exhibiting black art. For the assumption is made that blacks have no money and whites are not interested.”

“Black artists are not dealt with on the same level as white artists,” adds Hendricks, a nationally known realist painter whose work often focuses on young black people in urban settings. “And good black artists in this country are just not well known enough.”

For their part, gallery owners in Philadelphia contend there is no racism. ”I select my artists based on the slides I see,” says Benjamin Mangel of the Mangel Gallery in Rittenhouse Square. “Many times, I have no idea if the artist is black or white. You just want the art to be very good.

“I would like to exhibit more black artists,” adds Mangel, who has shown Hendricks’ paintings since 1980. “When I had a group showing of black

artists, I was accused of not showing any women artists.”

Like some artists, some art experts say the problem with gallery owners starts with education.

“Black art is not taught to future curators and critics in colleges. Only the latest edition of H.W. Janson’s standard text, ‘The History of Art,’ mentions a black artist. It’s not racism per se – it’s lack of familiarity,” says Liz Harris, who used to own two galleries in Boston and represents several black artists.

There are other issues to contend with when the topic of racism in the art world comes up. One concerns the subjects that black artists decide to paint.

“The notion of ‘black art’ is still confused. People think of it as political or protest art. That’s not all there is,” says Harris.

Some black artists are so reluctant to be categorized by race that they refuse to participate in shows like those tied to Black History Month, she says; she herself looks forward to the day when art won’t wear a racial label, ”when there will be just ‘art,’ period.”

“I don’t want to be viewed as an artist who paints the civil rights struggle,” adds Beatty, who is represented by a Washington, D.C., gallery. ”I am tired of hearing about it and would prefer to paint exactly what I want. That is the kind of freedom I enjoy.”

But can black art sell? And if it can’t, is that the reason why it is often rejected by some galleries?

Many gallery owners and artists believe that customers demand broad themes, that a painting of a ghetto scene will not appeal to everyone.

“Obviously, even a warm painting of a black family with black babies is not going to sit in a white family’s living room,” says John McDaniel, an abstract painter and exhibition coordinator at the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum.

Others say that the marketability issue is simply a smoke screen for discrimination.

“It all depends on the policy of the gallery owner,” says Massey. “If the gallery owner is prejudiced, then you’ll see no black artists exhibited. Good art will sell if it is shown. There are black and white customers out there who are interested in this kind of work.”

“Very often, as in many disciplines, the subject is misunderstood,” says Evelyn Redcross, who along with her husband, Mercer, runs the October Gallery at 3805 Lancaster Ave. in Powelton Village. “Some of the galleries don’t respond to black art because they don’t understand it, or they refuse to open their minds to what black artists are doing.”

Redcross and her husband, who had been avid art collectors for the last 12 years, opened the October Gallery in 1985 to give exposure to black artists who were ignored by the big Center City galleries.

“There were people out there who demanded the art,” says Evelyn Redcross.

The Lucien Crump Art Gallery, at Germantown Avenue and Johnson Street in Germantown, also carries original art, posters and lithographs, mostly by black artists.

Crump, a painter and former junior high school art teacher, opened the neighborhood gallery seven years ago.

“When I decided to open, I wanted this gallery to be a service to the community,” Crump says. “If I made money, that was fine, but at the time, it wasn’t important.” Today Crump is thriving on a block where few stores selling more practical goods and merchandise succeed.

“My message to the American art family,” says Hendricks, “comes from the mouth of Hobson Pittman: ‘You are too good not to be better.’ ”