Along the continuum of representational art, Simmie Knox takes the Hippocratic Oath to do no harm.

A nip here. A dissolved wrinkle there. In the end, a portrait is supposed to “make you look your best,” says the man who wields a tiny brush to encapsulate the spirits of Muhammad Ali, Bill and Hilary Clinton and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

And, at age 77, Knox is the unofficial portraitist for trailblazing African Americans.

He has painted baseball legend Hank Aaron; media magnate Oprah Winfrey; former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall; comedian Bill Cosby; Bishop Quintin Primo, the first black bishop elected in the dioceses of Delaware and Chicago; David Dinkins, the first and only black mayor of New York City; and Peter Spencer, founder of A.U.M.P. Church in Wilmington, the first independent black church in the nation.

Knox, himself, was the first African-American artist to create an official White House portrait, painting former President Bill Clinton and first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton in 2000.

“Sometimes it’s not always the size of your hammer or the size of the rock, but it’s how often you hit that rock,” he is fond of saying.

Training his eye

A childhood friend of Aaron, Knox practiced baseball with bottle caps and broomsticks until he got socked in the face with a real ball at the age of 13.

Doctors suggested that he retrain his eye by sketching. At the time, it wasn’t socially acceptable for young blacks in Alabama to study art, so the nuns at Knox’s school arranged for private drawing lessons with a postal carrier.

Practice made perfect. A selection of Knox’s portraits, along with his abstract landscapes and still-life drawings, are on display through March 21 in the lobby of the Citizens Bank Center in downtown Wilmington. The collection features portraits of all five current state Supreme Court justices, the first time the oil paintings have been assembled in one space.

Last month, the Delaware Humanities Forum premiered a short film about Knox’s life, “Strokes of Justice,” emphasizing his strong ties to the First State.

Knox lived in Delaware for 13 years, and received game-changing art training at the University of Delaware before moving on to Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia. He also taught art in high schools for four years in Wilmington.

“It’s a very tender and honest presentation,” says Marilyn Whittington, executive director for the humanities forum, which spent $20,000 on the film project.

Coming full circle

Born in 1935 to a family of poor sharecroppers in Aliceville, Ala., Knox moved to Milford more than two decades later on the heels of his parents, who were seeking work up north.

After a three-year stint in the Army, he enrolled in Delaware State College as a biology major, producing stellar drawings of microorganisms, before heading to UD.

As one of only a half-dozen black students at the school, Knox recalled feeling isolated in the dining hall, ignored by white students.

“Every now and then, some brave soul followed the courage of conviction,” he says.

While attending school and working at a textile factory in Milford, Del., he painted an 11-year-old Randy Holland at the request of Holland’s father, who worked with Knox at the factory. Nearly a half-century later, Holland returned the favor by asking Knox to paint his portrait when he was appointed to the Delaware Supreme Court.

In 1961, Knox completed his first notable portrait — a full-size self-portrait depicting a young man as an emerging force, his browstrong, his expression enigmatic.

“I wasn’t trying to communicate anything except looking in the mirror,” he explains.

Knox chose to pursue the current fad, abstract art, exhibiting alongside heavy hitters like Hans Hofmann and Roy Lichtenstein. He learned tricks that later influenced his portraits, such as manipulating warm colors to make objects pop and using cool colors to help them recede, creating a 3-D canvas.

In 1971, he was honored in the “Thirty-Second Biennial of Contemporary American Painting” at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

But he missed the challenge of painting the human face, each one different than the next. “If I talk to you for five minutes, I have you pretty much sized up,” he says.

Most difficult are the hands, he continues, simulating the blood flow around the joints. In his portrait of Darnell Dockett, defensive tackle for the Arizona Cardinals and father of Knox’s grandson, the hands are crossed on the player’s hulking chest with a prominent tattoo “Laugh now, cry later.”

Judges appear less imposing. Often, they are surrounded by objects that have shaped their lives, from family portraits to stuffed ducks.

In painting then-Justice Marshall, Knox manipulated a smile, narrowing the eyes and thinning out the lips.

“He gave me a serious look but I wanted to make him look pleasant,” remembers Knox.

Marshall kept the painting behind his desk and joked to Knox that he wanted to be known as the “hanging judge,” the artist recalls.

Plum assignment

Knox had his “personal Super Bowl” moment in 2000, when he was selected to paint the Clintons. The New York Times and a host of other publications came calling and the president praised Knox as “a part of America’s promise.”

Gone were the days when subjects would sit for two hours a day for weeks on end without changing clothes. For President Clinton, Knox made do with 45 minutes, snapping photos in a frenzy.

It took Knox several months to complete the presidential portrait, submitting five poses for Clinton to review. The two bonded over a shared passion for jazz.

In the end, Clinton chose a standing pose, one hand resting self-assuredly in his pocket, surrounded by an American flag and military medallions.

Initially, the first lady disliked the way her hand grazed a table, so Knox tweaked it.

“I didn’t get anything out of the Bush administration,” he notes. Indeed, the only Republicans Knox has painted were Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood and freed slave and famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass but, as Knox notes, “He had no choice.”

After earning his degrees, Knox moved to Washington to earn a living as an artist serving the capital coterie. Now, working from his home’s converted garage in Silver Spring, Md., the father of three charges $18,000 to $60,000 per portrait, depending on size and complexity. He routinely works from photographs and his portraits are imbued with the vibrant clarity of a photo.

It is a highly subjective craft, where reputation is paramount and a commission can collapse if a subject prefers a brown dress to red. Incidentally, Oprah was a vision in red in her 6-foot-tall portrait.

Knox also has completed at least a dozen portraits for the Cosby family — early supporters of his work — including painting Cosby’s wife, Camille, four times because it “wasn’t quite right.”

Recently, he finished portraits of U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and former Aetna CEO Ron Williams. Knox also created a bronze sculpture of the first African-American mayor of Baltimore, the late Clarence “Du” Burns. Destined for Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, the sculpture depicts Burns holding the hand of a small child, modeled by Knox’s grandson.

Breathing life in

In Knox’s down time, which is becoming more common in a troubled economy, he focuses on landscapes and still-life paintings. He manages to capture the personality of a ripe pomegranate or the curled lip of a tulip.

Last month, the dapper Knox attended the opening of his exhibit in Wilmington. Soon, he was surrounded, flipping through his iPhone camera roll to dazzle guests with other examples of his portraiture.

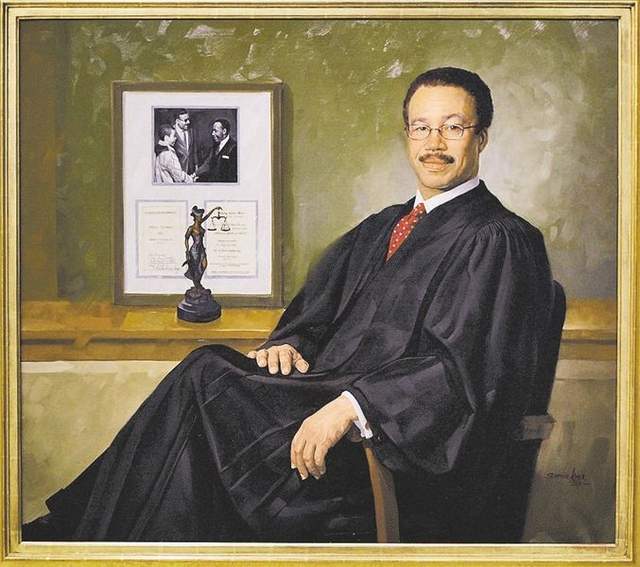

Among the attendees was one of Knox’s subjects, Chief District Judge Gregory Sleet, the first African American to be appointed U.S. Attorney in Delaware and the first to be appointed to the federal bench in the state.

Sleet applauded Knox for putting him at ease during the portrait-making process. Sleet is portrayed as relaxed and approachable, surrounded by the scales of justice, and a photograph of him as a young boy meeting Martin Luther King Jr. at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. Sleet’s father, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Moneta Sleet Jr., introduced his son to the civil rights leader.

“My father was probably the greatest influence on my life,” says Sleet, in explaining why he chose to include the photo.

Knox “breathes a life into a flower or judge,” says Citizens Bank gallery director Jerry Bilton, while confronting some of the eternal questions of art: “What is illusion? What is truth?”