Black artists in America have been among the most invisible of Ralph Ellison’s “invisible men”; it has been only relatively recently that the best of them have received any meaningful recognition.

One is reminded of this poignant circumstance by the experience of two black artists who did achieve some degree of professional success, Dox Thrash and Claude Clark.

Both were natives of Georgia who settled in Philadelphia. Both managed to attend art school – Thrash before he came here, Clark after – and both were active in the local graphic arts workshop run by the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration during the 1930s.

Thrash, an innovative printmaker who developed a new intaglio process, died here in 1965 at the age of 73. Clark, born Nov. 11, 1915, is still active as a painter and teacher in Oakland, Calif.

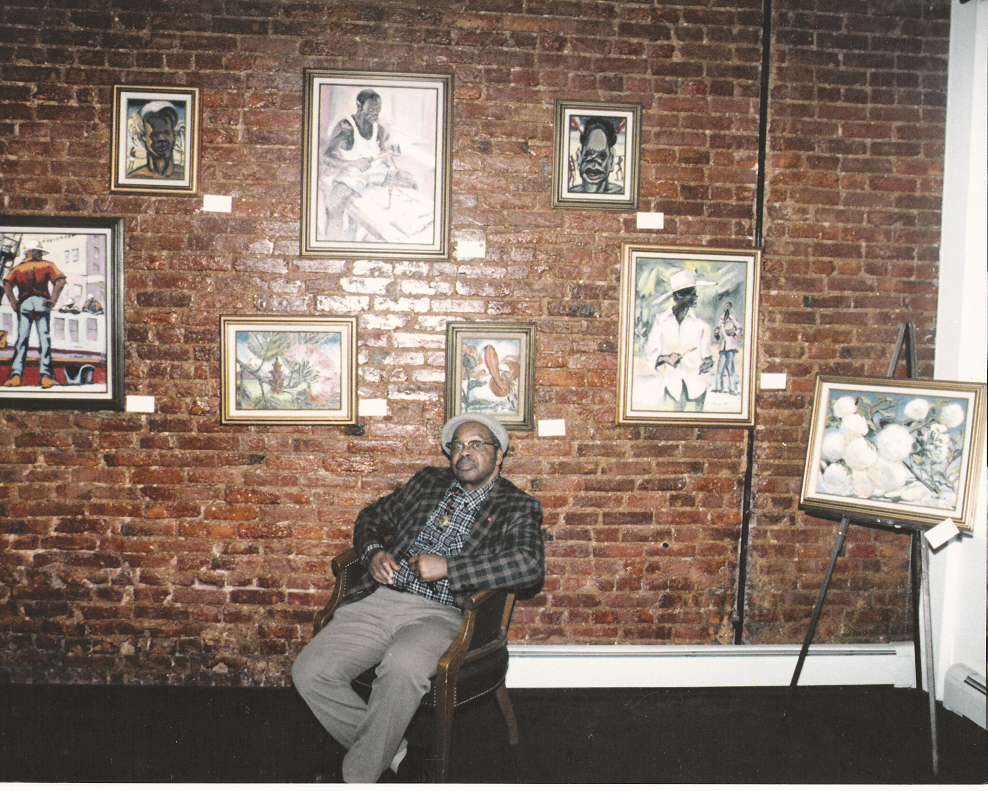

By coincidence, each has an exhibition in the city at the moment: Thrash at the Free Library of Philadelphia on Logan Square and Clark at the October Gallery, 3805 Lancaster Ave.

The Thrash exhibition, which will be up through May 29 in the library’s print and picture department, consists of more than 50 prints in various mediums and one watercolor-and-ink drawing. The Clark show, on view daily through March 15, is mainly oil paintings, with a few prints.

Although the exhibitions are quite different in many ways, they have common denominators of skill, determination and pride, both individual and communal. Each artist is, in his own way, a social realist. Each deals with black subject matter; Thrash’s is American, Clark’s more cosmopolitan in venturing into Africa and the Caribbean.

Neither is an artist of exceptional stylistic originality or visual perception – Thrash’s work, for example, is very similar to that of other social realists of 50 years ago. Yet each has created work that resonates with truth and humanity and, not incidentally, pride of heritage.

Thrash’s career is perhaps typical of many of his generation, black and white. It was characterized by years of scuffling and making do, of drifting

from city to city – as Thrash wrote in his memoirs, of “hobo-ing, working part time on odd jobs with the idea of observing, drawing and painting people of America. Especially the Negro.”

Thrash picked up some art training at the Art Institute of Chicago, both before and after World War I, during which he served in the Army.

He landed in Philadelphia after the war and decided to stay. He made his first prints under the tutelage of Earl Horter at the Graphic Sketch Club, later the Fleisher Art Memorial. In 1935 he hooked in with the fine-arts section of the WPA’s Federal Arts Program, which ran a workshop above Benny the Bum’s restaurant at 311 S. Broad St.

It was in the workshop that Thrash developed a graphic technique, an intaglio process called the carbograph, that would earn him modest fame. Two friends, Michael J. Gallagher and Hubert Mesibov, share credit with him for perfecting it.

Basically, Thrash discovered that a copper etching plate could be roughed up, or “grained,” by scrubbing it with crystals of silicon carbide, a very hard and sharp abrasive known commercially as Carborundum. After a plate had been so treated, a drawing could be transferred to it and an image created by working the roughened surface with tools.

When the plate was inked, the parts left rough would hold more ink and print dark; areas that had been smoothed or flattened with the tools would print lighter. It’s a process similar in concept to aquatint, and it’s still used by some artists today.

Thrash made a number of prints in the carbograph process, which produces a sculptural, tonal image rather than a linear one. He also made lithographs and etchings and some paintings.

In 1943, the WPA gave the Free Library a collection of about 70 prints that Thrash had made during the federal program. David King, head librarian in the print and picture department, has drawn the library’s show from this collection. He also included a section of carbographs made by some of Thrash’s contemporaries, including Gallagher and Mesibov.

The collection is primarily portraits, with some scenes from rural Georgia, some from urban Philadelphia and some of workers. The prints are undated but are believed to have been made between 1935 and 1942, when Thrash was involved with the WPA workshop.

Their taut composition style expresses the blunt, streetwise realism of the 1930s. The portraits are deceptively simple studies of Thrash’s friends, with unpretentious titles such as Linda, Ebony Joe and Charlott, but they are rendered with such quiet authority and dignity as to be almost iconic.

Thrash’s portrayals of workers display the typically muscular energy of Depression-era realism, but he could also be spirited and playful, as in a print of a man serenading a woman called Inveigling – the title conveys the mood precisely.

Thrash had a keen eye for street detail, displayed in an etching called Morley Court, and he could also appreciate the formal possibilities inherent in an ordinary group of houses, portrayed in a little gem of an aquatint called Suburbia.

He worked at a variety of jobs during his life, including railroad porter, steamship steward and house painter. He also said he had toured in vaudeville with a man named Whistling Rufus. His art never supported him, and when he died he was given only a brief and perfunctory obituary.

Thrash was one of many artists, kept afloat by the WPA during the Depression, whose art faded into obscurity after the project ended.

Claude Clark, on the other hand, was more fortunate – not only did he benefit from solid professional training, he has been able to earn a living teaching what he practices, although within the black community, and his paintings sell today at four-figure prices.

Clark moved with his family from Georgia to Philadelphia when he was 7, attended Roxborough Junior-Senior High School and won a four-year scholarship to Philadelphia College of Art.

From PCA, where for lack of money to buy canvas he often painted on window shades, he went to the Barnes Foundation in Merion, where he studied for four years. Eventually he earned a bachelor’s degree at Sacramento (Calif.) State

College and a master’s in painting from the University of California at Berkeley.

Clark has been a professor of art at Talladega College, Alabama, and he has traveled widely through the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America and Africa.

His travels provided the subject material for the paintings he’s showing at October; they’re essentially what in the 19th century would have been called genre painting.

Clark paints in a vigorous but disciplined style, using a palette knife to create passages of broken color. It’s a very physical approach that’s accentuated by Clark’s high-key Caribbean palette of bright, energetic color suffused with clear, brilliant light.

His works, like Thrash’s, express black experience from a distinctly black point of view, but they do so within a broadly humanistic framework that doesn’t require the viewer to have access to that experience.

Clark is represented in the national traveling exhibition “Hidden Heritage: Afro-American Art 1800-1950.” When that show opens at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Aug. 20, we will be able to better understand how little of the black visual tradition we have been allowed to see, and how much we have to learn from it.

*

The Thrash exhibition is on view in the print and picture department of the Free Library on Logan Square (686-5451) Monday through Friday from 9 to 5. Hours at October Gallery (387-5090) are Monday through Thursday 10 to 6, Friday 10 to 8 and Saturday and Sunday noon to 6.