Caroline Tiger, For The Inquirer

Posted: Friday, November 30, 2012, 2:53 PM

Reporters are always asking Paula Scher and Seymour Chwast when they’re going to collaborate. That’s what happens when you’re famous, married, and working in the same industry. Scher and Chwast are firm: Never. “It’s not so much our lack of interest than it would break up our marriage,” Chwast (pronounced Kwahst) tells me, because I can’t resist asking, either.

Later I ask Scher. “No,” she says. “We can’t collaborate. It’s impossible.”

Besides the relational politics, they work in different styles and on different scales. She communicates through typography, and he uses illustration. She works on buildings and multinational corporate identities. He does editorial illustrations for magazines and designs books and posters. But isn’t the exhibit “Double Portrait: Paula Scher and Seymour Chwast, Graphic Designers,” opening Sunday at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a collaboration of sorts? The museum’s description declares this is the first time these designers, who happen to be married, have exhibited jointly. It turns out the day-to-day of Scher and Chwast’s intertwined creative lives is less about togetherness than it is about two individuals designing side by side.

The exhibit depicts that duality. Inside the gallery, two gigantic lowercase a’s face off on opposing walls. One, designed by Chwast in the 1960s for packaging for India ink, is curvaceous, funny, and suggestive of an ink drop. The other, designed by Scher for a Type Directors Club project, is aggressive and geometric. If the a’s are Chwast and Scher sitting at the heads of the dinner table, the perpendicular walls crowded with posters are the offspring of these two fertile minds. That noisy symphony of type and images displays another shared trait – these are not designers who hold back.

“There’s a commonality of interest,” says Kathy Hiesinger, the museum’s curator of European Decorative Arts after 1700. “They share a sense of humor, and both enjoy retrieving images from the past.” Steven Heller, the prolific design writer and longtime friend of the couple’s, says, “Both have invented more than one visual language that draws on other sources but can be discerned as their own.”

Scher, 64, and Chwast, 81, married for the first time in 1973, divorced five years later, and remarried in 1989. Being 17 years older than Scher, Chwast already had a reputation as an influential graphic designer when they first met. Scher showed up in his office with her portfolio, fresh from the Tyler School of Art. He had already influenced her – as he did an entire generation of graphic design students – in art school.

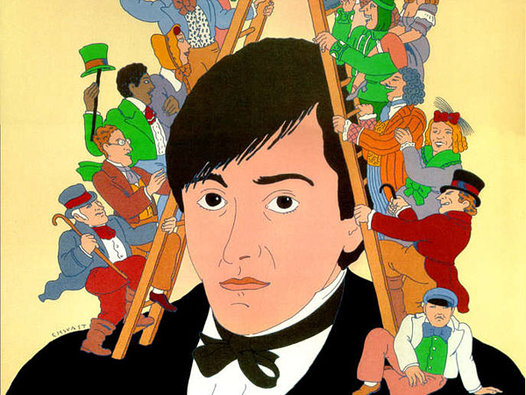

In 1954, Chwast cofounded Push Pin Studios with Edward Sorel, Reynold Ruffins, and Milton Glaser, classmates from Cooper Union. His allusions to 19th-century woodcuts and surrealism (a couch with human legs, a skyscraper culminating in a fountain pen nib) in posters, advertising, and in the Push Pin Graphic, a promotional magazine that disseminated the studio’s work, were an affront to Swiss modernism. That prevalent style at the time preached straight lines, grid systems, and a lack of imagery. Helvetica, the Swiss style’s favored font, stands as straight-backed as a soldier, but Chwast’s type and illustrations are kinetic, colorful, and loose.

Mixing historical styles is common today, but in the ’50s and ’60s, it was radical. “This was way before anyone was talking about postmodernism,” Hiesinger says. In art school and in the ’70s when Scher was designing album covers at CBS Records, she was influenced by Push Pin to similarly rebel against Swiss modernism. As she explained during a talk about her life in design, Helvetica felt fascist. She responded to art nouveau, pop art, and Victorian typography “not because I was being a postmodernist or historicist, but because I hated Helvetica.”

At Tyler, because her illustration was stronger than her typography, design professor Stanislaw Zagorski suggested illustrating with type to imbue it with the same spirit. “He said the type could function the same way that illustration does,” Scher says. “That’s when I became interested in what letter forms look like and mean in terms of communication.” Push Pin’s work was a shining example.

In 1991 Scher joined design consultancy Pentagram as a partner. The posters and identity she created there for New York’s Public Theatre, with words dancing alongside Savion Glover, became a much-copied style.

Scher famously sketched the logo for Citibank on the back of a napkin after an initial client meeting, but still had to sit through a year of process meetings. Her own process is a lightning strike, while Chwast’s is more deliberate. He gets up early and draws all day. That has affected her greatly. “I really have been influenced by his dedication to his work and the sort of time he puts into it,” Scher says. “Sometimes I was forced to work all the time because I didn’t have anything else to do. I was married to him and that’s what he would do. And then, ultimately, it became habit.”

Major museum shows of graphic design are relatively rare. There have been three in the United States since 1988: Cooper Hewitt’s “Graphic Design: Now in Production” (2012), Walker Art Center’s “Graphic Design in America” (1988), and the Cooper Hewitt’s “Mixing Messages” (1996). In conjunction with the Art Museum exhibit, Scher and Chwast will receive Collab’s 22d Design Excellence award. The award has been around since 1986, but this is only the second time it has gone to graphic designers. “It seemed like it was long overdue,” Heisinger says, adding, “It was an obvious twofer.” It was obvious because together the couple’s work makes up a profound slice of graphic design history, and reflects our country’s cultural and political history dating to the mid-20th century. Also, Seymour Chwast and Paula Scher are kind of like the Warren Beatty and Annette Bening of graphic design – except Beatty and Bening are less opposed to collaborating.

Part of the appeal of the exhibit, running through April 14, is the voyeuristic thrill of seeing, through the close juxtaposition of their bodies of groundbreaking work, how the two have influenced each other. There is something intimate about those images and type waving, chattering, and hollering at one another across the room. Underlying it all are open-ended questions that ultimately make these icons relatable: “If I had not been with him, would I have lived my life exactly this way,” Scher says, “or am I with him because I always wanted to do it this way? I don’t know. I ask myself this question all the time.”