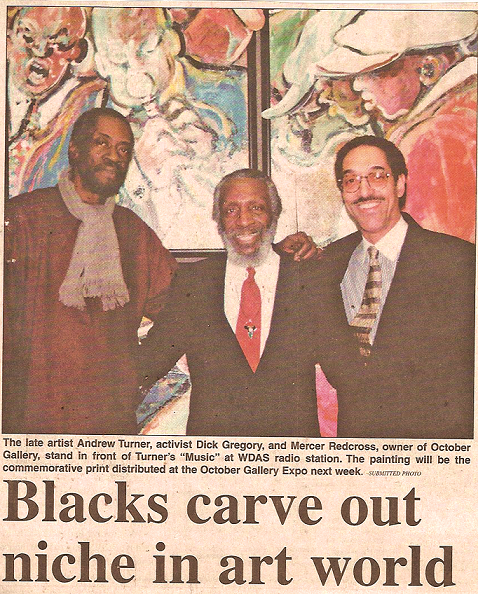

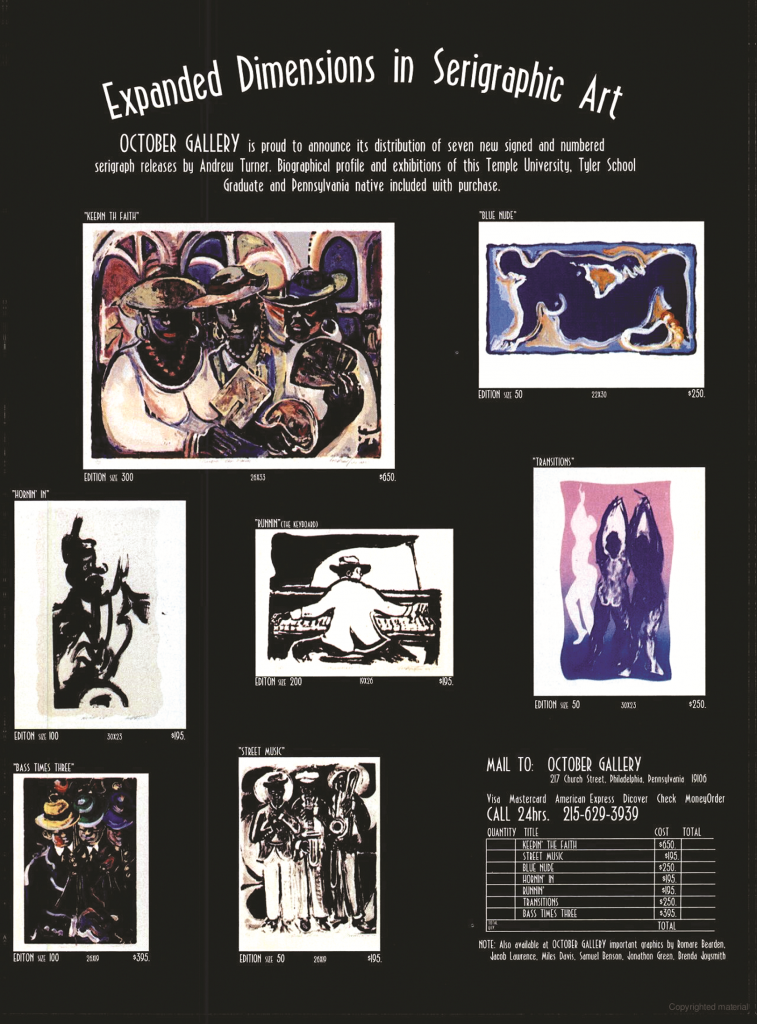

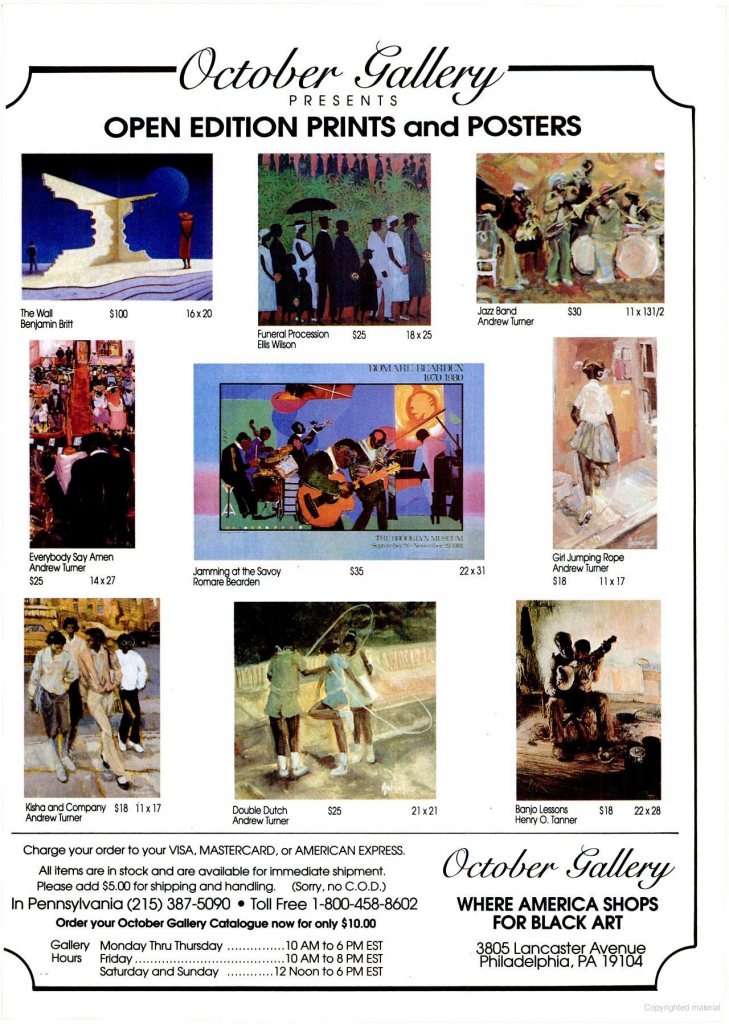

artists such as Tom McKinney, Ellen Powell Tiberino and Richard Watson. Sharing the walls are the works of Dane Tilghman, Andrew Turner, Dressler Smith and other emerging artists who have been hard pressed to find showcases.

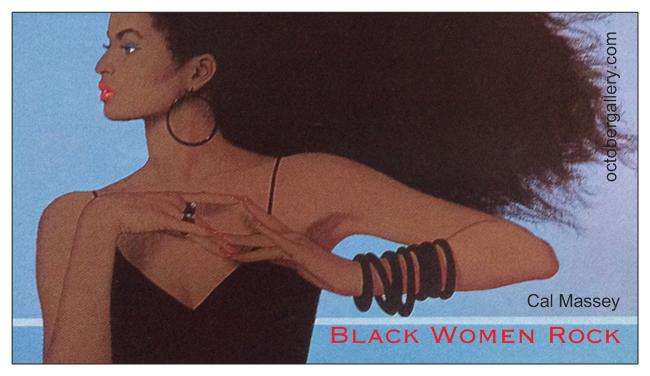

The galleries brim not only with art once rarely seen, but also with new consumers eager to buy. These clients, predominantly black, range from working people with modest poster-and-print budgets to lawyers, physicians, politicians and other professionals who spend big bucks on original pieces. They are graduates fresh out of college, retirees and newlyweds who now believe it is more hip to start housekeeping with a Cal Massey print than a Cuisinart.

“Black people have always bought fine clothes and fine cars, rather than fine art,” said Crump, a painter for more than 40 years whose work is in many private and public collections. “People could always spend $30, $40 on a Saturday night. Now they are spending it on art.”

As Thomas Gunn of Laverock, Montgomery County, an international money broker, put it, his 125-piece collection is “fun. I just enjoy what I buy, and if it appreciates in value, that’s fine. But if not, I still enjoy it.”

In the city, the boom in black art centers on the Lucien Crump Art Gallery and the newer Chosen Image, Heritage, Mocha, Phoenix Rising, Crockett Atelier and October galleries. But it is not confined to Philadelphia. This decade has seen the creation of such thriving businesses as the Malcolm Brown Gallery in Shaker Heights, Ohio; the N’Namdi Gallery of Detroit; Isobel Neal Gallery in Chicago; Liz Harris Gallery in Boston; June Kelly in New York, and Sun Gallery in Washington.

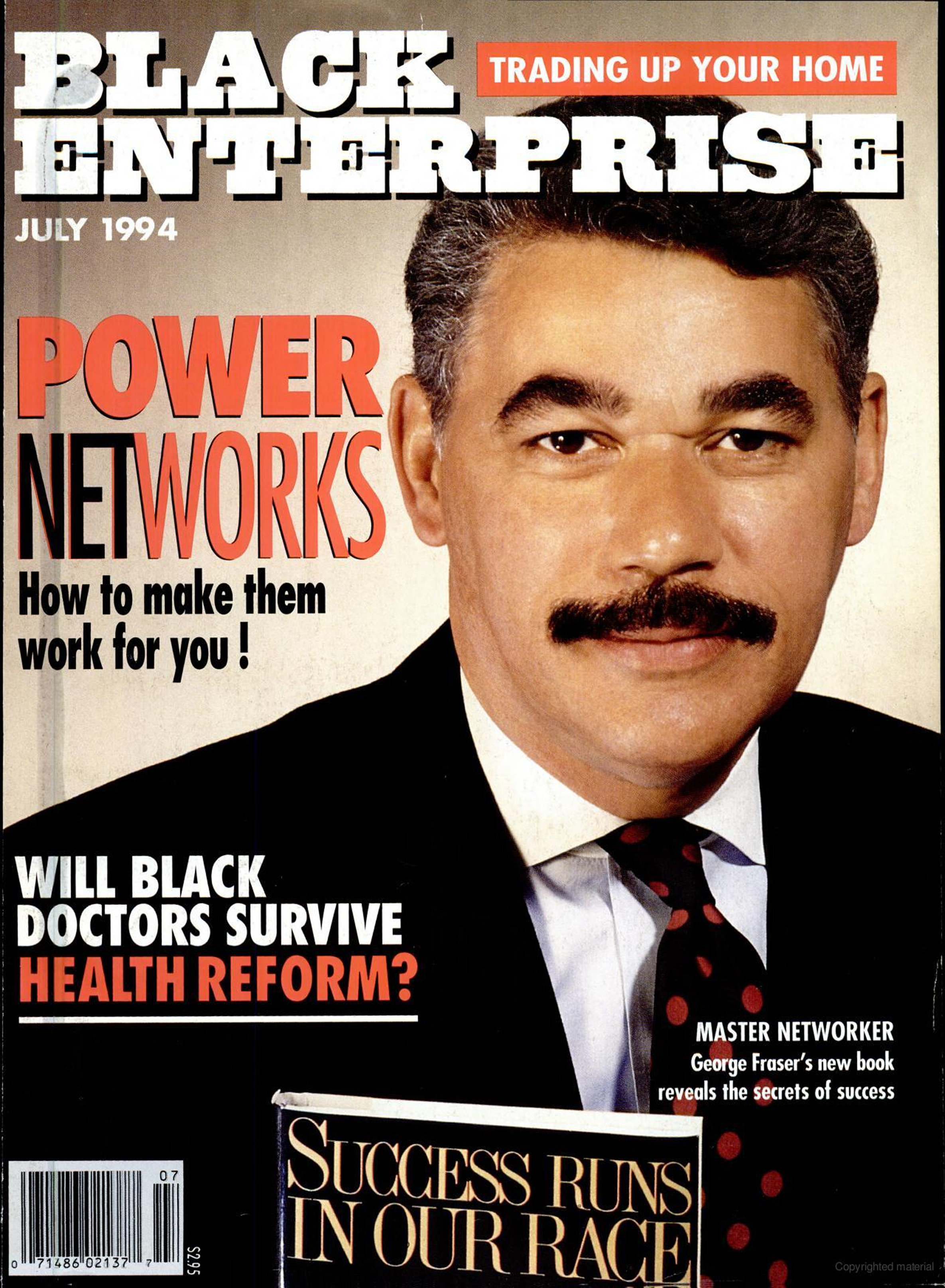

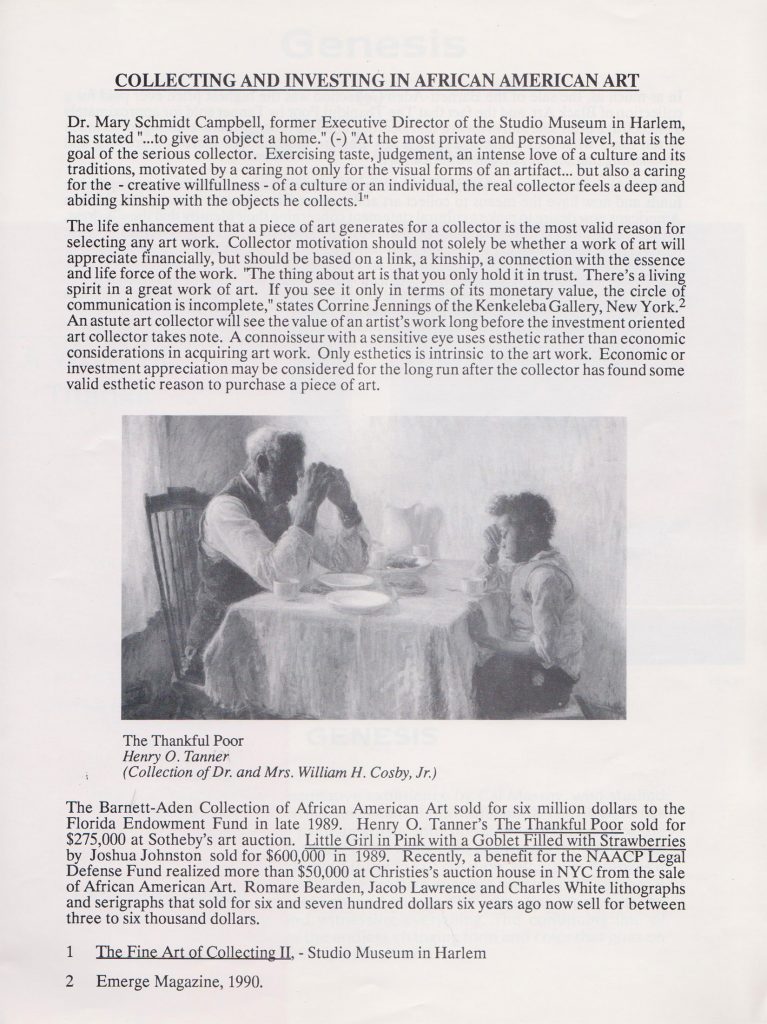

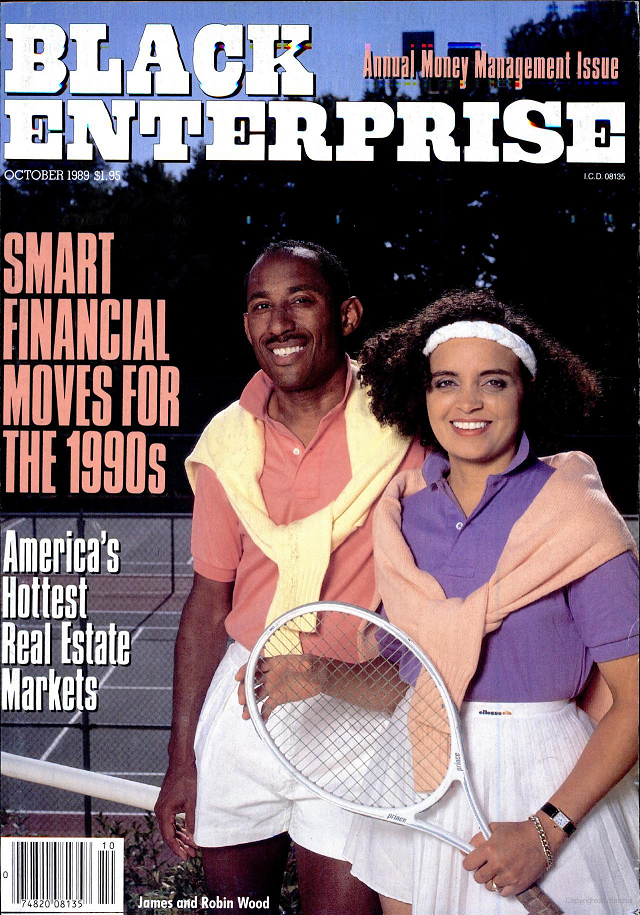

The phenomenon has grown under the media spotlight. Black Enterprise and Essence magazines have regularly published articles on the importance of supporting artists and the investment potential in art purchases. Bill Cosby’s TV home is filled with art by Brenda Joysmith and Ellis Wilson, among others; Cosby collects originals, such as fellow Philadelphian Henry Ossawa Tanner’s The Thankful Poor, which he purchased in 1981 for $250,000. At the time, it was a record price for a work by a black artist.

More significant, experts say, the burgeoning of black galleries has been a direct result of the art establishment’s systematic exclusion of artists of color, as documented in a report on New York galleries and museum exhibitions during the last seven years.

Compiled by Howardena Pindell, a Philadelphia-born artist and former associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art, the report found that as of mid-1988, 39 galleries – including nearly all of the most prestigious spaces – represented only white artists; only 10 galleries represented a selection of

artists that was less than 90 percent white, and one of those was in the process of closing.

This, Pindell wrote, in a state where 11,000 black, Asian, Hispanic and Native American artists live and work.

Counteracting that exclusion have been not only the galleries but also African arts festivals and, in some cities, a handful of pioneering museums.

Philadelphians’ interest has been piqued by the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, where there have been at least 100 shows and hundreds of thousands of visitors since it opened in 1976.

The museum’s role, executive director Rowena Stewart said, is “helping people become aware that within our community there is a core group of artists who are affordable and speak for us. Now it’s almost a no-no to walk into someone’s home and not see any Afro-American art. The trend is to have at least one piece, particularly if you are of Afro-American descent.”

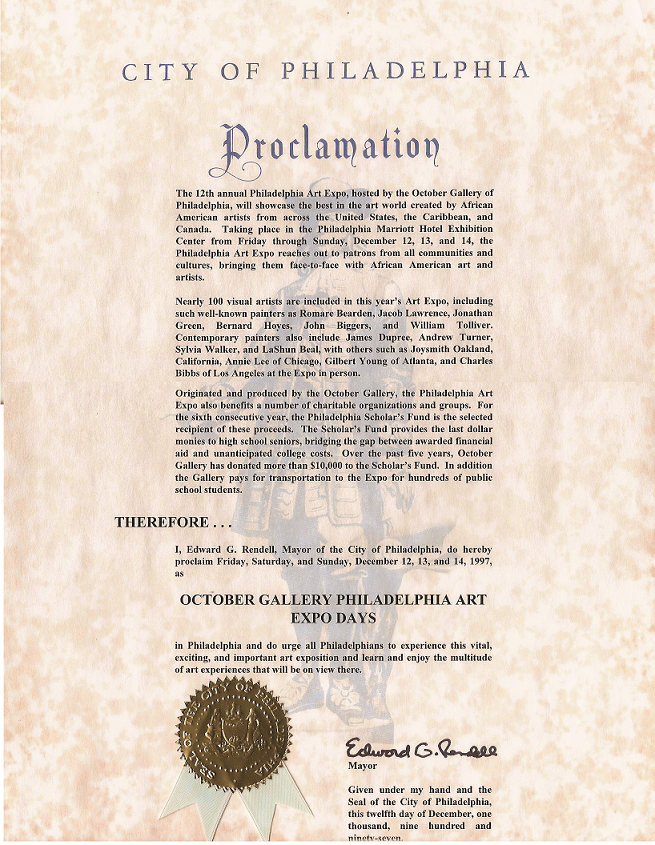

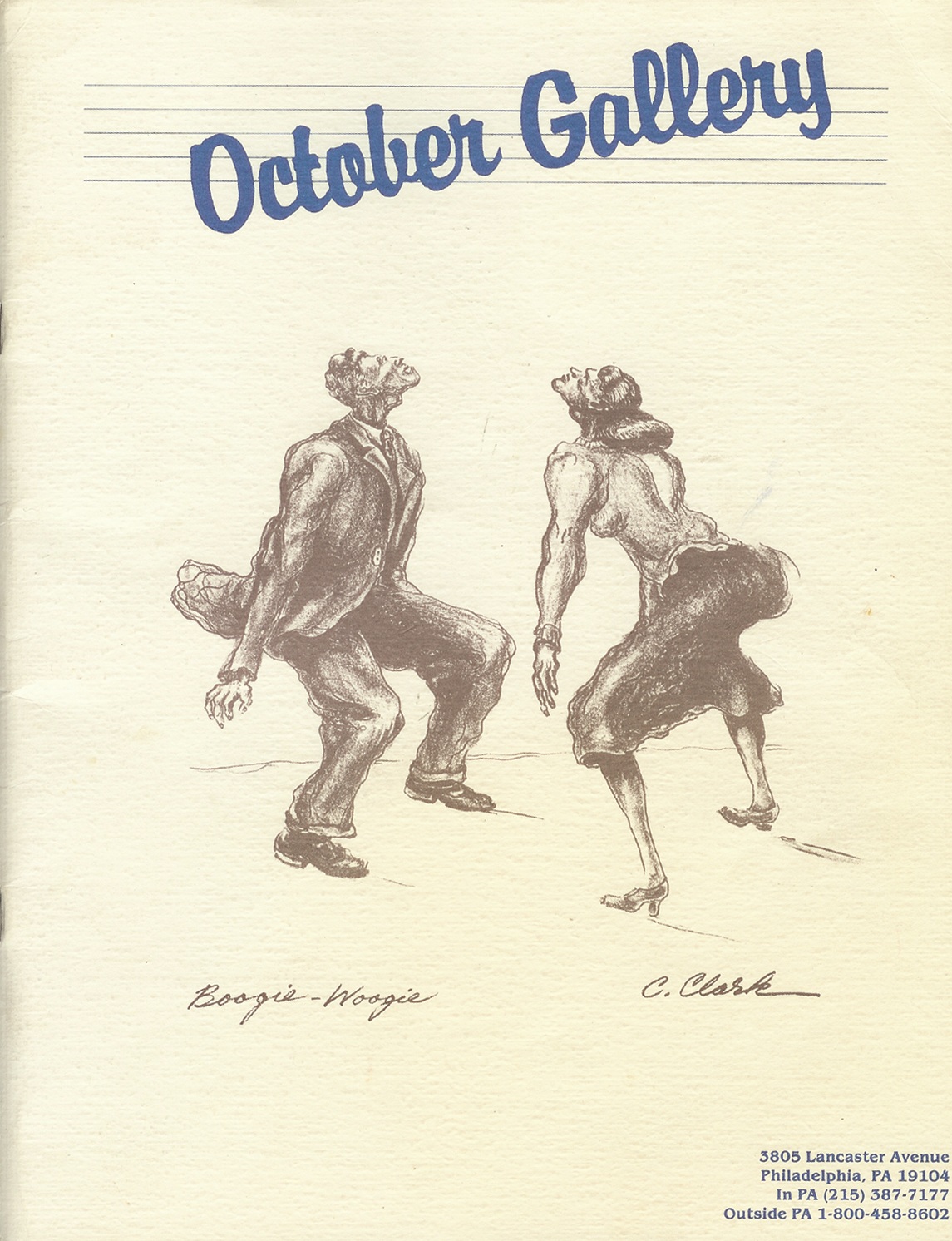

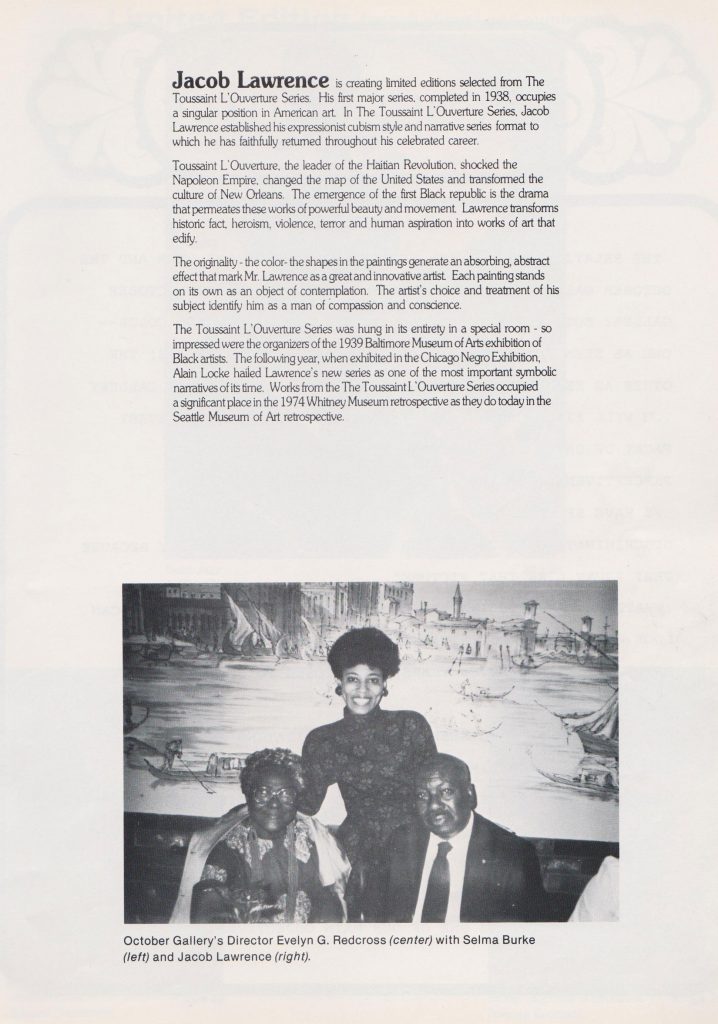

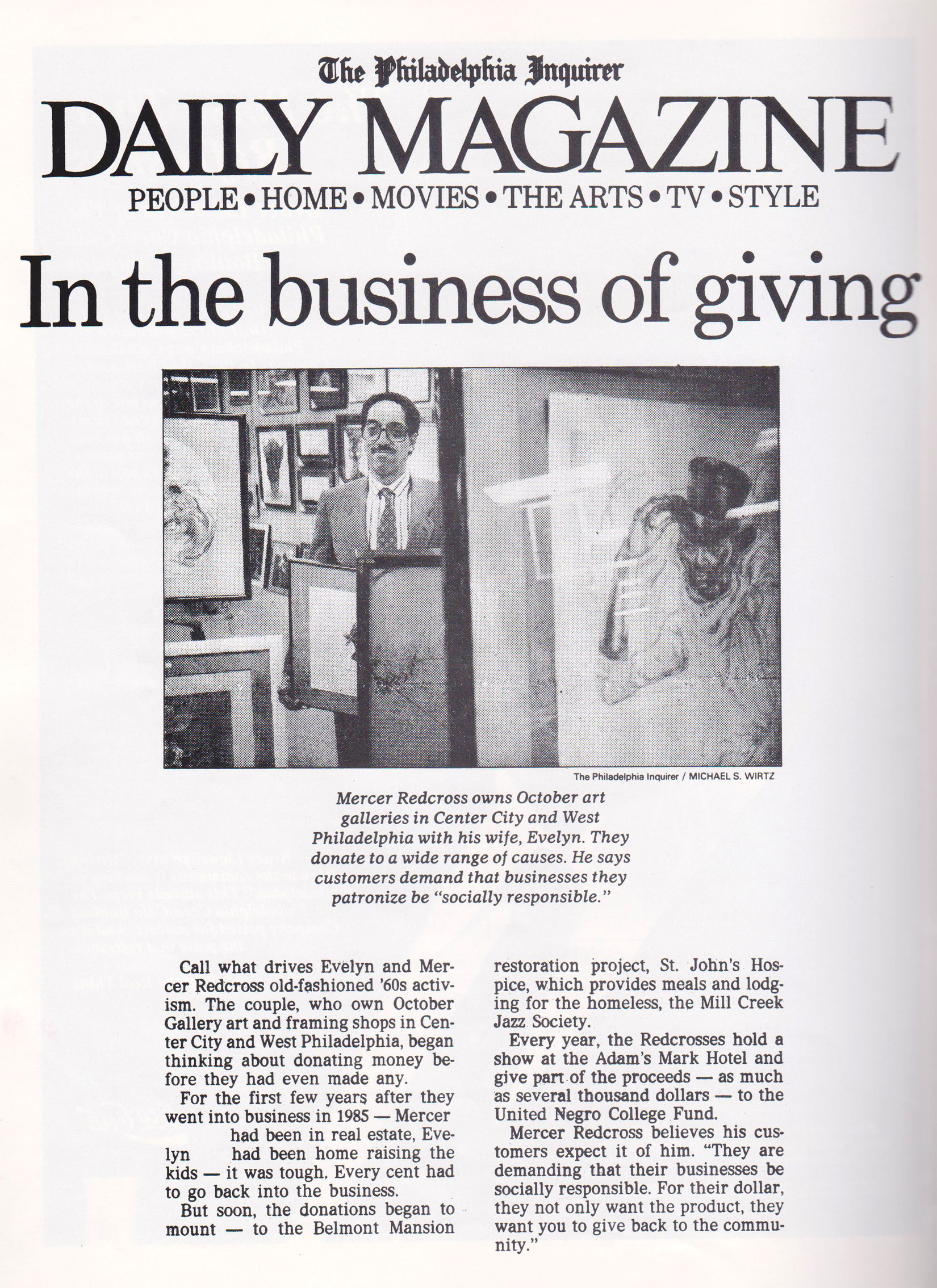

Indeed, Mercer Redcross, who with his wife, Evelyn, owns the five-year-old October Gallery, 3805 Lancaster Ave. in Powelton, contended that Philadelphia was becoming “the national mecca for all kinds of black artists and black art” – for reasons as diverse as the mere presence of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a supportive city government and the magnetic pull of an already large and respected community of black artists.

There is no one black aesthetic, no single definitive quality that identifies an artist’s work as African-American, any more than there is for European, Asian or Caucasian art. And many black artists aim to broaden the term black art until it loses its stereotype – namely, representational images of urban bliss or misery and 1960s political protest art.

However, most new buyers of black art are seeking just that: realistic, figurative “work that reflects themselves and their experiences,” said Redcross. “People are hungry for something that reminds them of themselves.”

George Nock, a former New York Jets running back who grew up in North Philadelphia, can attest to that hunger.

Wildlife and fantasy were the primary inspirations for Nock, a Ben Franklin High School graduate who does pen-and-ink drawings, acrylics, watercolors and sculpture.

Since he began creating representational art inspired by black heritage about three years ago, he said, “I kept recalling the response. My sales had been about 50-50 wildlife and fantasy. Since then, 70 percent of my sales have been (figurative) African-American art.”

Nock’s one-man show at the Crump Gallery features 60 pieces of all these kinds of work. The show opened Saturday and will continue through Aug. 25 at the gallery, at Germantown Avenue and Johnson Street.

The gallery owners speak with an almost missionary zeal when they discuss their work. “We are experiencing an aesthetic growth that reflects our (African) heritage,” Crump said. “When it was time to plant crops, we used to put a piece of sculpture in the home; we used sculptured works in all recreational events, like weddings, harvests and so on.”

At Chosen Image, 6521 N. Broad St. in East Oak Lane, owner Sandra Broadus sees “a new awakening for our people. It’s growing every day and it’s important to educate and nurture our customers through this process, and make it possible for as many artists to share in this as possible.”

One early black-art advocate is white. For 20 years, Sande Webster of Sande Webster Gallery, 2018 Locust St., has sought to focus attention on artists whose work “continues to be stereotyped” and kept at the periphery of the art world.

Among Center City’s gallery owners, she said, she remains alone in her crusade.

Webster is voluble in her praise for the new black galleries, and is counting on them to quickly educate new buyers to appreciate more than figurative work.

Joe Tiberino, a white artist, has sponsored black-art showcases at Bacchanal, the South Street bar/restaurant he has co-owned for eight years, accepting just enough from sales to recover costs. Last year’s sculpture show of black cowboys by Phil Sumpter “went over very well,” he said.

“It’s not about profit for us.”

The galleries, needless to say, do not have that luxury. At the October Gallery, the Redcrosses envision glory days ahead. Recalling the 1970s’ golden era of the city’s music industry spearheaded by soul producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, Redcross said the couple aimed “to become the Gamble and Huff of the black art world.”

The Redcrosses, who founded the gallery in 1984, pioneered selling black art in hotels across the nation. They have an inventory in the thousands, they publish prints and they constantly promote their business, often by donating partial proceeds to such causes as the United Negro College Fund.

Ismail and Sharifa Abdul-Hamid, who own Heritage Gallery, 51 N. Third St. in Old City, have more modest goals. The gallery, which opened June 24, also carries Native American and Mexican-American art, and its current show, closing Sunday, combines both.

“The marketplace is barely scratched,” said Ismail Abdul-Hamid. “Our competition is not each other, it’s the video store, the record store, the gold jewelry. So people are beginning to buy seven albums instead of 10 and then buying the art.”

Another couple, Wanda and Terry Crockett of Crockett Atelier, plan to move their business from their Oak Lane home into a commercial space “within 18 months to two years,” said Wanda Crockett. “We’re specializing in finding and restoring to their rightful place older artists who couldn’t get into traditional galleries and literally threw their works in the basement.”

Lucien Crump, the acknowledged dean of the group, has competition right in Germantown, from Sameriah Allen of Mocha Gallery, 10-12 Church Lane. But, Allen said, “Lucien and I complement each other; he refers people to me, I sell prints of his work. We’re a lower-end gallery in price, we try to accommodate all budgets.”

Chosen Image’s Sandra Broadus founded her business because “people kept coming in wanting to buy my personal collection off the walls.” Her two-year- old gallery carries “50 percent traditional African scenes, 40 percent modern African-American art and only rare or unique abstracts and landscapes.”

Not all the stories are happy ones. Lucinda Johnson of Phoenix Rising, 2247 N. Broad St. in North Philadelphia, is struggling to recoup a $10,000 loss

from a burglary. She is re-establishing her business from her home, coping with the struggling artists she handles, serving private clients and working a full-time job with the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program. Like most of these owners, she said, “the bulk of my gallery income comes from the framing I do, so the break-in devastated me. But I really want to remain in North Philadelphia.”

With all her problems, Johnson remains committed to her field and to educating prospective buyers, such as Clarence Weaver, who browsed through Crump’s gallery recently.

Said the Philadelphia police officer, “It will be nice to have my history where I can look up and see it every day.”