The Afro-Futurist painter talks about Kanye, Common, and living like a shark.

By Elly Fishman

Hebru Brantley has been putting his aesthetic mark on Chicago for years. He spent much of his youth tagging its walls, honing the graffiti style he eventually brought inside. Now the 29-year-old artist— who’s shown in Atlanta, Seattle, New York, and Los Angeles—is about to open his biggest local exhibit to date: Afro-Futurism: Impossible View, at the Zhou B Art Center.

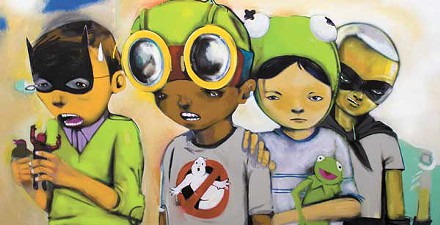

Brantley’s studio still reflects a kid’s visual imagination. If Peter Pan author J.M. Barrie were a black graffiti artist, this could be his Neverland. Spray-painted cartoon villains glower, young heroes parachute through sea-green clouds, and lost boys stalk about in dinosaur suits. The tables are piled with Marvel comics and action figures, and a homemade model airplane the size of a condor dives from the ceiling.

Like Neverland, Brantley’s work contains much that’s harsh, even cruel. Several of his paintings reflect the stereotypes drawn into old Tex Avery and Chuck Jones cartoons. Though he never gives the sense of being on a soapbox about it, Brantley often references the imagery of racism.

Who were your first influences in art?

I idolized my older brother, who was a first-generation Tony Hawk skater kid. He’d cover everything with stickers, logos, and character drawings. I first learned graffiti through the sketchbooks that he’d leave around the house.

When did you start tagging?

In middle school. Back then the biggest thing was scratch tags. You’d take sandpaper or gravel, get on the bus, and scratch your name in different shapes. The goal was to get your scratches on as many CTA lines as possible. Later, in high school, I started stealing spray cans and writing on anything with no shame. There was no art to it—it was just about how much you could get your name up.

Was there a moment when you began to think about art?

My junior year of high school, my first art teacher challenged me to expand my work. She showed me fine art, and I began to understand it and no longer dismiss it. . . .

She gave me a book of pop art. Obviously, Andy Warhol was the godfather. I admired him. And then I found Jean-Michel Basquiat. My mom bought me a book of Basquiat’s work that showed the span of his career. I became very much a bastard child of Basquiat. To see someone so young make it happen was very inspiring.

How would you describe your work?

I consider myself an Afro-Futurist. I think my work merges the new and neon with more traditional brushstrokes and techniques. I’m a child of popular culture and heavily influenced by cartoons, comic books, and television. I also have a strong affinity for Japanimation.

Would you say your art is about being a black American?

No. Well, I guess it just depends on my mood. Last year I spent a lot of time getting things off my chest. I had a show called Lions Disguised as Lambs in Seattle, and a lot of imagery was based around early racist cartoons. Impossible View is lighter in nature and just comes from a place of imagination.

When you directed me to your studio, you told me to follow the music. Does music play an important role in your creative process?

Music is a huge component of what I do. I think it’s what influences me the most.

What music did you listen to while preparing for Impossible View?

For this show I’ve been listening to my hometown heroes, Kanye West and Common.

What makes them heroes?

They’re products of Chicago who actually made it. Also, a lot of their music is extremely soulful and it’s music I can relate to. A lot of trials that Kanye and Common talk about are coming from a familiar place. It’s like they are one of your own, one of your boys.

What are the trials that you most relate to?

On his Be album, Common talks about young black males who have to choose a direction in life. For example, they wonder whether to pursue higher education or come home and hustle for their families. And how sometimes it can be hard to look towards next week when this one is so bleak.

Are there personal hardships that most affected you?

Well, definitely losing my parents back-to-back. Three years ago, my mom was diagnosed with cancer, and then, immediately, so was my stepdad. I’d been living and making art in LA, but I dropped all that was me, all that made me happy, to come back and take care of my siblings and basically watch my parents—who were only 55 and 58—die.

How did that experience affect your work?

Initially, negatively. It was a very dark time and I went into a dark place. Sometimes I didn’t understand what my mission was. I didn’t want to create anything, and what I did create was shit. It was a creative depression.

What changed?

I was taking my mom to chemo for a year, and she could see how rattled I was. So she suggested I bring my sketchbook. So I started writing down things she’d say and drawing the scenes we were in: her in the hospital bed, us in the waiting room, etc. After she passed in 2009 and I was looking for the answer, I felt like that sketchbook was a codex. Making art is what I needed to do. Since then, the floodgates have opened. I know that has to do with my mom.

What was something she told you that sticks with you?

She told me to be sharklike. I hold true to that.

What does that mean?

To always keep moving and be ferocious in whatever I do.

Tell me about Flyboy, the character you’ve created for Impossible View.

The Flyboy is my homage to the [African-American] Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. They were just so cool. The character is like my version of Captain America. Captain America’s success in the war is glorified in Marvel comics, and I think to be a black man during that period of time and be given license to fly—to escape—is worth celebrating. v

Care to comment? Find this interview at chicagoreader.com/galleries.