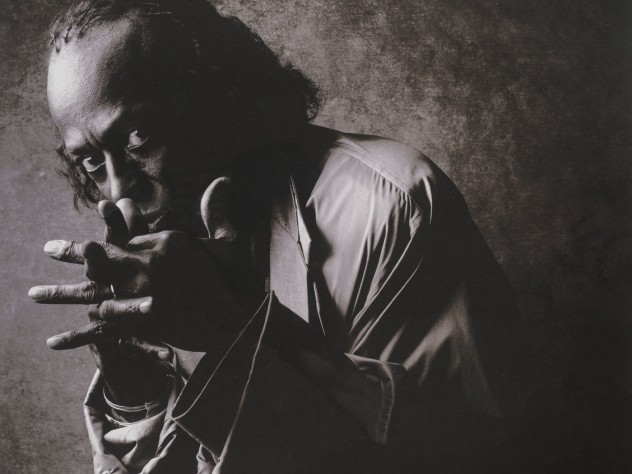

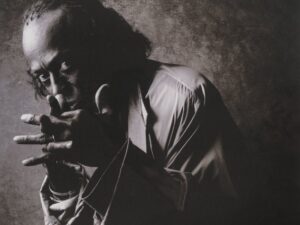

Miles Davis, photographed by William Coupon

Photograph courtesy of the Cooper Gallery

THE FRONT HALL of the Cooper Gallery on Mount Auburn Street, what appear to be two bubble-shaped lanterns hang from the ceiling—but instead of beaming down light to illuminate the art, they pipe in music for visitors standing beneath. In the rooms beyond, other sounds beckon: fuzzy radio broadcasts melting into the clean chords from a lone piano.

Showing 70 works in a range of media (including six sound installations), and bridging two of the University’s museums, the multi-part exhibition Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes opened last week at the Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art and the Harvard Art Museums. The exhibition grew from the art-history course taught by visiting professor David Bindman and Clowes professor of fine arts and professor of African and African American studies Suzanne Preston Blier. Housed at the Harvard Art Museums and drawn from their permanent collection, “Form” collects 18 works—from Jackson Pollack prints to Viktor Schreckengost’s blue art deco punch bowl—that were inspired by jazz’s early and midcentury social scene, or by rhythm or improvisation. The ephemera displayed in the “Performance” section, also curated by Blier and Bindman, couldn’t fit in the museums’ teaching galleries—but on its own, couldn’t fill the Cooper Gallery, either. The two scholars suggested that director Vera Ingrid Grant add a third, more contemporary, component: “Notes,” which collects late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century works.

“I wanted this to be a call and response, curatorially,” says Grant. Kept visually distinct, the sections feel like the individual instruments in a trio, their voices trading places and overlapping. Where “Performance” displays album covers, children’s books, and other objects in neutral white spaces, the walls for “Notes” are painted cobalt. Grant borrowed that blue from artist Lina Viktor after visiting Viktor’s New York workspace, which was drenched in the opulent hue.

In the Cooper Gallery, Viktor’s Arcadia—an art deco-inspired work painted with pure 24-karat gold—hangs, glamorous, next to elements of Christopher Myers’s Echo in the Bones, inspired by musical funeral traditions from New Orleans and Vietnam. A band uniform, embroidered with the almost rune-like symbols the National Guard sprayed on homes after Hurricane Katrina, hangs in a brass display case. Next to it stands a composition of brass instruments fused together, looking “phantasmagoric,” as Grant puts it. As a symbol of life springing from decay, the sculpture also looks distinctly, defiantly fungal.

Birds—caged and escaped, singing and flying—have figured prominently throughout the history of jazz, and of African-American arts more broadly, Grant explains: think Nina Simone’s “Blackbird” and John Coltrane’s Bye Bye Blackbird. In the exhibition, they are a visual motif stitching the installations together. Illustrated birds decorate the pages of picture books, while a black and white portrait of saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker by Hugh Bell hangs on the neighboring wall. Walter Davis’s painting Black Bird Totem and his collage Bird Flightrecapitulate the theme in joyous colors and abstract shapes.

The flock comes home to roost at the end of the exhibit. In Whitfield Lovell’s Servilis, stuffed ravens stand on pedestals in front of a large group portrait, burned into wood, of six aproned women. The connection to music is not immediately obvious. Interpretations of Lovell’s historic subject matter typically consider the women’s servitude or freedom, and their physical solidarity: leaning on each other’s shoulders, arms looped around waists. The installation’s placement in the jazz exhibition—with its frozen, inquisitive birds—calls attention to the subjects’ silence.

Servilis stares across the room at jazz artist Jason Moran’s STAGED: Three Deuces, a mixed media installation recreating that historic New York venue, with its padded walls and ornately embossed ceiling. Three Deuces was a “jazz mecca” of the bebop era, Moran told an interviewer in 2015, when his work was originally mounted at the Venice Biennale. Its close confines didn’t allow room for dancing; listeners had to sit, instead. STAGED: Three Deuces seems like a stuffed specimen itself: a once-living thing from a now-vanished habitat, not undignified, just strangely sad, in its state of careful preservation. Next to a bass laid on its side in its case, the self-playing Steinway (performing music by Moran on the hour) takes on a ghostly aspect.

Moran extended his original composition, “He Cares,” to 12 minutes for the exhibition; other works have were also specially expanded, like the new, enlarged print of a photograph by Ming Smith, “Invisible Man With Borders,” which is displayed in a frame that shows off its emulsion edges. Though Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes may seem to end on a lonely note, its different pieces add up to an exhibition less interested in pursuing a single thesis than in amplifying a conversation.

“Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes“ is open at the Cooper Gallery and Harvard Art Museums through May 8, with the exception of Jason Moran’s “STAGED: Three Deuces,” on view through April 1.