by Matthea Harvey

BOMB 100/Summer 2007, ART

I’ve been thinking about Kara Walker’s work for a long time. Two years ago, a bleeding barn from one of her watercolors appeared in one of my poems. About a month ago I finished writing a book of poems, Modern Life, which is populated by catgoats and centaurs, civilians and soldiers, and I found myself wanting to talk to her. Who better to ask about the division/fusion of past and present, how to live in the middle of “yes” and “no,” where the real and imagined intersect?

People have been paying attention—both positive and negative—to Walker’s work since she became one of the youngest artists to receive a MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship, in 1997. Perhaps that is only fitting, because Walker is certainly paying attention as she cuts along the dotted lines of race and gender, manipulates paper marionettes on film, and conjures the gray area as she types in black ink on white paper. The world, as seen through Walker’s eyes, is tragicomic, pornographic. She asks her audience to perch on hyphens, slide down slashes—and when we emerge, we have a bristling intuition of boundaries and stereotypes that is entirely new.

This year a traveling retrospective takes the measure of her drawings, paintings, installations, and the cutout silhouettes for which she is best known, as well as the films that she has added to her repertoire in the last few years. Organized by the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love, opens at the Whitney Museum of Anerican Art, New York, in October and travels to the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, in February 2008.

Matthea Harvey Let’s talk about hybrids. In your work, you have white swans with human heads—

Kara Walker The swans with the black heads came very organically. I was thinking about objects of beauty and destruction. I first used them in a piece meant to be a comment on my ownership of stereotypical black forms. This conversation was happening as to who has the right to use stereotypical images of blacks. Do they reinforce cultural values that set African Americans back generations, or are they fair-game images that preexist you and me?

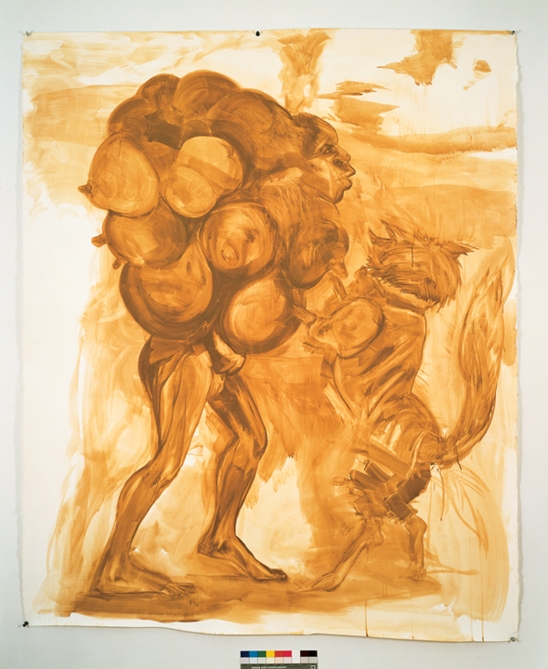

MH What about your more mythical cutouts of children with tails or a figure who is half ship, half woman?

KW They are all over the place, aren’t they? They are like little walking fables. I’m externalizing what can’t be expressed verbally. I’m thinking of the little girl holding her tail, but each figure is unreal or hybrid to begin with, so to call this one a shadow or pickaninny or Topsy . . . is she a real character? Is she an externalization of a part of me? There are so many fallacies, so many myths about the absence of humanity in women, in blacks, that I don’t even think it’s abnormal that she has a tail.

MH You work in many different mediums, including paper cutouts, gouache mixed with coffee, brass rubbings, overhead projectors . . . . Lately you have been making films in which you manipulate cutout figures behind a scrim, with shadow and cut-paper sets. These are like narrative animations of your silhouettes. Have you found that each medium leads you in different directions? What are the frustrations and/or delights of each one?

KW I’ve done two films and a video, and the frustrations there are the lack of touch and immediacy. On the other hand, because I’ve made mainly puppet films, there’s a great deal of another sort of touch. We’re making puppets and manipulating them, and they develop personalities. It’s a little goofy, but I’m completely surprised by the performance aspect. I can leave the studio at the end of the day and feel like something happened, something that’s counter to what’s happening out in the world, and it has developed a language and a universe. With the film I made last year, at the end of every day I felt as if I had just made a painting. (laughter) Like, “This is what I want a painting to do!” It’s activated all the way through, not just on the surface. The story happens over time; it unfolds. Very often I picture things in my head all at once. In the film it’s happening on both sides of the canvas.

MH In the film, you emphasize the artificiality of the puppet play. The sticks you use to manipulate the puppets are visible, and you also allow the viewers to see your hands and face, and those of the other puppeteers, semi-visible behind the scrim. What was that decision about?

KW I didn’t want to pretend that it was an illusion. When you’re working with a screen, you’re wearing a mask and putting on a performance. There’s an acknowledgement of the presence of the subject, and then there’s the story, and the subject and the story are always moving back and forth between reality and fiction. I did two live puppet-show performances—something I will never do again—but I discovered that me with a screen or a mask is a whole different personality. I noticed it, I felt it, and I didn’t really like myself afterward. Leading up to getting behind the scrim, I was scared silly, an increasingly erratic nervous wreck. Afterward, I was like Joe Cool. I was in LA, too, which didn’t help. It was a little creepy. I felt that somehow I had to live in the world that the mask created.

MH I know I’ve had moments where I’ve written a poem that horrifies me. I think, “Oh my God, I didn’t mean to have someone having sex with a pig in my poem.” But then I feel like I have to live with it. (laughter)

KW Yeah, narratives are forever.

MH You have talked about the different reactions viewers have when they come to your work. I’ve experienced all sorts of emotions myself looking at it. What emotions do you have when you’re creating the pieces? Do you blush or laugh or cry?

KW Yeah, that’s the hard part: I can’t make this work if I don’t feel something along those lines. I’ve definitely laughed or cackled out of absolute surprise at myself, and I have probably cried enough tears to flood the city. Shame is, I think, the most interesting state because it’s so transgressive, so pervasive. It can occupy all your other, more familiar states: happiness, anger, rage, fear . . . . It’s interesting to put that out on the table, to elicit feelings of shame from others—“Come and join me in my shame!” It is a little peculiar.

I got an email last year from a student at a community college in Arkansas. He told me that in his Art Appreciation class, they watched a video about me and my work, and the reactions from the white students in the class were so violent and cruel. Like, she can only get away with making this kind of work because she’s black! If a white man made this work, he’d be lynched. Language like that. And I’m thinking, “Is this wishful thinking?” The lynching thing frightened me. That was the kind of reaction that I might imagine is out there, but to hear it up close made me a little more afraid about how people respond.

MH You had a show at The Metropolitan Museum of Art last year called “After the Deluge,” which was a response to Hurricane Katrina. What did it feel like to be dealing with such a recent political phenomenon?

KW The problem that I was encountering, like a lot of artists after 9/11, after this disaster in the Gulf, is that it seems impossible to respond adequately through your own work without seeming self-serving or overdetermined or earnest to the point that nobody is going to listen. I was having trouble figuring out how to insinuate myself into the museum in a way that seemed interesting. My feeling was that there was something really vital that I wanted us all—whoever us all is—to hold onto in terms of being confronted with images of disaster over which we may or may not have control. I felt that art could address those underlying currents before they disappeared or were washed away by political positioning or jockeying for the best story.

MH What are you working on right now? I see some interesting pieces on the wall over there—

KW This is so new that I don’t know if I can name it. There was the Walker Art Center show in Minneapolis, and then the requisite hole of non-production, and I’ve been trying to work my way out of that gradually. The writing on the wall and the images from the Internet are just the beginnings of my convoluted method: writing somewhat spontaneously, and then researching through the depths of what I’m thinking.

Last week I was very annoyed about the state of painting, annoyed with a lot of questions about my uncertainty or my lack of participation in conversations about painting. I’m not really actively painting, so it feels like I’ve missed the boat on what people are talking about in that world. I was looking up contemporary artists who use terms like “image-making strategies.” My sense was that in the sensibility of these artists there’s something corrupt about the picture plane—that any image or mark is just a recitation of other terms. There’s no longer any search for originality. The effort of painting seems to have to do with strategizing: putting the viewer in a position where they’re looking at an intentionally shallow painting—shallow in a way that feels different from, say, Warhol’s shallow. Maybe I’ve over-interpreted it, but I think that Warhol’s sense of shallow is incredibly soulful. It’s open and generous in a dumb kind of way, like, “Here it is!” Yet it’s accepting of its own fallibility and humanity.

MH So you feel that contemporary painting is too veiled, too ironic?

KW Yeah. My feelings grew out of my teaching experiences at Columbia. I was getting the sense that a really good painting only succeeds if it’s abject to the point of suicide. It’s a site of no hope. As if a good painting can no longer stand to see itself alive, thriving. An artist in the program, who is not American, created some work that didn’t have that sensibility. It was very much image- and memory-oriented. The critique veered around to, “You have this very conservative view of painting.” And I thought, “What does that mean?” Was it, “Oh, well, he’s an ethnic artist, so he can tell us a story.” I wondered if that was condescending. It was really complicated.

MH What is teaching like for you?

KW It’s like that. (laughter) I come away with a lot of problems and doubts and insecurities. It’s a little like being in school. It’s a learning process.

MH You’ve mentioned that your work is often taken as a rewriting of history, what was actually happening in the antebellum South. But you’ve asserted that your work is fantasy clothed in historical outfits. I am curious about whether those fantasies are in the historical outfits from the get-go, or whether you transpose them afterward.

KW I think it’s a combination. On my new typewriter last night I wrote a couple of sentences about memory, whether or not there is such a thing as a past and a present, or if the present is just like the past with new clothes on. It was a very frustrating thought, and it started to sound very conservative, which I didn’t want. I wrote something like, “Women always wind up being women.” I read somewhere about how Frederick Douglass’s narrative, or variations on his narrative, have this very American rags-to-riches or boy-to-man construction, whereas—and maybe I just intuited this—women’s narratives are confronted with silences: rape, child death, illegitimate childbirth. Even today, these are the threads that seem to continually bind women together: some determined by the culture, some determined by biology. That’s where women always end up being women: you can do x, y, and z to become a human being, but you’re suddenly confronted with being a woman again in a very limited sense: being a sexual object, and a sexual object who might also become a mother, willingly or unwillingly.

I’m sorry. I just digress. That’s all I do. (laughter)

MH No, it’s great. Digressing is how we get somewhere. Plus this seems to relate to your use or appropriation or revision of offensive language and images. I want to ask you about the resolution that was approved in New York on February 28 to ban the use of the N-word. The person who sponsored it, Councilman Leroy Comrey, argued that the word was derived solely from hate and anger, and that its meaning cannot be changed.

KW I don’t know. I do think that there is a proper use of profanity that is incredibly useful and shouldn’t be washed out or sullied by overuse. Its meaning cannot be changed—but then again, we are constantly changing the meanings of words. It is up to each successive generation. You know, I was sitting in the park yesterday testing out my typewriter, and this little boy looked at this alien object, like, “Cool!” I am typing away, yeah, this is neat, and then his mother took him along. It reminded me of a situation where I was playing a Stevie Wonder song, “Pastime Paradise,” and somebody came in and said, “I don’t know that Puff Daddy song.” I had always assumed that when things are sampled or reused, some of their original content comes with them, but now I don’t think that is the case at all. I have been making my work under this assumption to some extent. I think it comes in waves. A certain moment opens a fissure and all the past comes flooding in.

MH Do you work on the typewriter a lot?

KW I do. Sometimes I write on the computer, but it doesn’t feel the same. I like the clackety-clack of the typewriter. It’s as if it answers. There’s a thought, and you put it down, letter by letter, and it answers back.

MH Does working on a typewriter feel connected to your use of the silhouettes? They are both antiquated mediums.

KW Maybe. Yeah—a little something that’s forgotten and shelved but still incredibly useful, or vital, that leads you to all sorts of other innovations. The typewriter leaves every flaw intact. When I write longhand, if all else fails, I can draw a picture. I can cover up the errors, the mistakes of switches in tense or grammar. With the typewriter, it’s, “I am flawed, but I’m going to keep trying!”

MH I’m glad you’re talking about the text in your work. I’m interested in the constant interplay between text and image in your pieces. Text makes its way onto the surface of your drawings, and your titles have subtitles. How do you think of their relation?

KW Well, sometimes I get mad at myself when I write on top of the drawing, because it seems like a giveaway. They might come off as too instructive, even if it’s written in the same spirit as a typed piece or a title. In my thinking, the word is a completely separate thing. It really sits off to the side, unless I write it underneath. The exceptions are the watercolors that were a response to accusations of irresponsibility to the black community. A suite of about eighty watercolors called Do You Like Crème in Your Coffee and Chocolate in Your Milk? which I worked on, diary-like, to deal with the letter-writing campaign started by Betye Saar and Howardena Pindell. I put a fair amount of trust in my visual “speaking” voice. I allowed myself to write and draw pretty freely over the pages of a notebook so that page by page I could ask and answer the question, “What is a ‘positive black image’?” Is a positive image one that is honest? And if so, to whom or what? I think that images, these hand-drawn characters I make, have the ambiguous duty of being both part of the real world (which is cruel and nasty) and the world of other images (which sometimes pretend to be noble, but are often concealing disgusting intentions).

MH I love your variety of titling strategies: You play with puns, as in African’t, Dawn of Ann, The Emancipation Approximation; you appropriate antebellum language, as in Missus K. Walker returns her thanks to the Ladies and Gentlemen of New York for the great Encouragement she has received from them, in the profession in which she has practiced in New England; and sometimes you give a series of pieces the same title, as in Negress Notes (Brown Follies). At what point do the titles arrive for you, and what function do they perform?

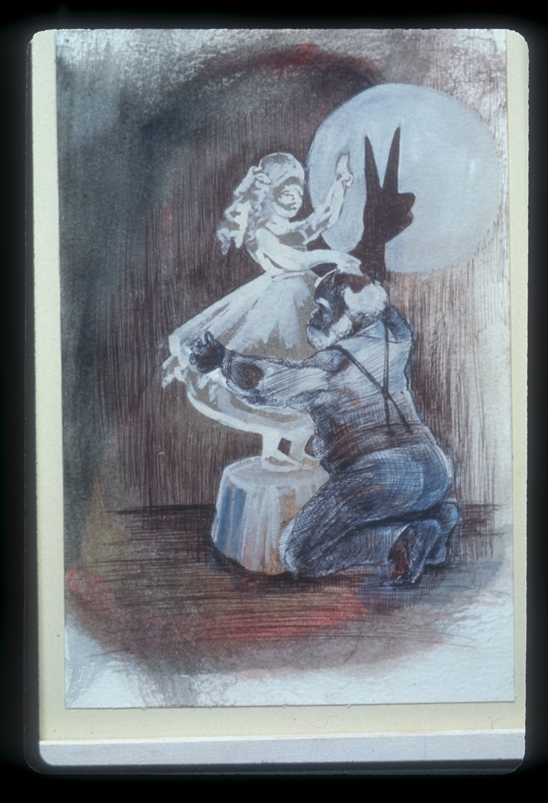

KW They’re the sideshow act. Just thought of that. (laughter) The image is that of a three-ring circus. I’ve never known how to concentrate on a three-ring circus. The title has its own agenda, which sometime runs counter to the rage in the piece. It can be a queasy invitation to this uncomfortable space. One of the pieces or situations that I was happiest with was when, over a couple of months, I sat and typed on note cards in the hopes of something arriving or making sense. Another month went by and I realized that I really needed some images. I thought I would try to use the note cards as a springboard for the images, although there was no one-to-one relation. The pictures I made are called American Primitives. Varying in size from six inches square to about nine by 12, they are pretty small, intimate ruminations on black figures plopped into a scene, like actors on a stage.

I feel like I’m constantly at step one of learning how to be an artist, or how to make art. I have an idealized folk artist in my mind. . . . I don’t know if it’s my calling, I don’t know if there’s a divine voice behind this, but I know that I have to do it. That was where the writing came from, and I kept the same method alive for making the images. The images were all gouache landscapes on gessoed panels with tissue-paper cutouts on top. I sat at my kitchen table and just cranked out one painting after another. It was very energetic and satisfying. And then there was this third moment when text came back in. Each one of the pieces had a title that had nothing to do with the initial writings, but I felt that I held a strange thread that connected them, from writing to image to writing again.

MH Could you give an example of one card, one image, and one title that came afterward?

KW The cards are dense. Lots of trying to figure out what the voice is, a voice that seems to shift character midsentence, from master to . . . There was one group of cards where I was thinking of myself as a New World black, like I have my own land that I can do anything with, but I have no tools and no skills. How do I create this project of a new society, given the scarcity of resources? I was trying to write from this debauched kind of leader position, which is what I was feeling like a little bit at home. (laughter) One of the images I painted was a tangle of branches, and two little faces in circles that became two suns. One has a whitish face, and the other has sort of black Negro features. They’re scowling at each other. I was doing these things like an assembly line. I had these two faces and the tangle of branches, and then I said, “What kind of cutout am I going to make?” I made another circle, and by accident there was a little cut in the paper already, so it looked like it was a smile, in profile. It just made me laugh. It went from this landscape that was not ever going to be completely developed properly, to Two Competing Suns and The Impostor, which became the title. I loved the title so much.

MH That’s one of my favorite pieces, and I love that title in particular. Wallace Stevens is a ridiculously good titler— Le Monocle de Mon Oncle or The Revolutionists Stop for Orangeade. Last weekend I was in Baltimore, at the American Visionary Art Museum and saw a painting by William Tyler, an outsider artist, with a great title: The Imposter Chicken Went Swimming in the Birdbath.

KW Wow. You didn’t get to the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum, speaking of great titles?

MH I did, and that’s a title I don’t know what to do with.

KW It’s a weird one. Blacks in Wax? It’s sort of jaunty and rolls off the tongue. I think it makes me smile too much. It runs counter to the missionary—I was going to say missionary position. (laughter) Missionary quality of the institution. The whole place runs counter to itself. It’s interestingly charged and problematic.

MH I noticed while I was there that they had one of the images you use in your visual essay in the catalogue for the Walker Art Center show—an image of little black children sitting in a tree, titled Blackbirds. Is that where you found that image?

KW No, it was a gift. Coco Fusco sent it to me. An eBay purchase. I need to thank her for that. Thank you, Coco.

MH What do you think its purpose is?

KW I’m not sure if it has a purpose. That’s what’s so peculiar about the whole black collectible phenomenon. So many objects and images serve absolutely no purpose. What’s the need to continually look at bodies in a particular way? It seems perverse.

MH You’ve said before that some of your favorite artists are anonymous. Do you have favorite pieces that you can describe?

KW Well, there’s one anonymous piece that I did a riff on a couple of years ago in this book called American Primitives—a very queer little painting called Darkytown. No knowledge of who could have made it, why it’s titled that, what the characters could have meant, but it epitomized something . . . . It was ludicrous in its formal construction, because there’s an attempt at single-point perspective that goes off in one direction, and there are black caricatures way too big in the foreground, and there’s a dog and some other little people, and a telephone or a telegraph wire. It looks like one of those Komar and Melamid Most Wanted paintings. It’s got everything: landscape, portrait, animal, perspective, illusion—

MH You liked that you didn’t know who had drawn it?

KW Well, I like that it’s shrouded in mystery.

MH At the Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore they have this amazing dress made in the ’30s by an anonymous woman who was institutionalized for schizophrenia. The hospital had a dress code and she crocheted this “horse dress” in response to the hospital’s policies. It’s the most incredibly beautiful, eerie, and defiant dress I’ve ever seen—the horse’s eyes are where the breasts would be, and there are abstracted hooves on the side.

KW It’s so interesting to have the need to externalize what can’t be processed internally.

MH Do you regret, resent, or relate to how much of your own biography is used in interpretations of your work?

KW It’s one of those things that makes me smile because it’s just a story. It has no relation to the truth of who I am or how I came to be. A few years ago a young historian, Gina Dent, gave a lecture about how often African American women, creative women, artists or writers, find that it’s not so much that their work is received critically as their body is received critically. Their whole body and biography become the source of query. The other part of her argument had to do with how often these same women have to resort to writing their own biographies or constructing their own critiques in order to counteract that.

MH In her book Seeing the Unspeakable, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw talks about how often writers scrutinize your appearance—

KW It just happened recently in an article about my willowy limbs. (laughter) It’s worthy of some commentary.

MH You’ve invented a persona in your work, “Kara Elizabeth Walker, an emancipated Negress and leader in her cause.” Could you talk about that?

KW Kara Walker the invented construct—I’ve never been asked about it. I don’t have an answer for it ready at hand. My graduate-school show was the first time there was an external narrative to what I was proposing to do, the work that I could have created if I had lived 150 or 200 years ago. If I had access to any tools at all, it might have been something to cut with or some paper—so the silhouettes seemed very accessible. Over the years, the persona has shifted here and there to reflect and hold onto this imaginary self of the past and reflect changes in my present circumstances. Like, at one point I added a “B” for my married, hyphenated last name. Then I got rid of the “B.” I am less interested in reinventing that character, because she has to position herself against or sidle up next to white or institutional power in this seductive and cagey way, and I can only do that so often without feeling a little queasy.

MH Can you tell me more about the idealized folk artist you mentioned having in your head?

KW Well, I didn’t have a certain kind of artist in mind. I’ve often responded to early American art that has the quality of “We’re not trained in Europe, we’re not going on the Grand Tour, we’re just trying to make pictures of what we see,” because it runs counter to my experience. I grew up around artists and art institutions, galleries, and students who were studying art. There’s nothing about me that doesn’t know how to paint, but I don’t trust my ability to paint, so I feel like I have to continually relearn it. My first real encounter with early American art and folk art was in college. I felt that I recognized a real humanity that I had been missing in modern painting. I don’t have any kind of animosity toward the modernists; it just felt incredibly subversive to me to like genre painting and pictures of things that are rendered with very little professional skill. It’s a little like the writing I like to do. It comes out with a kind of force, and it’s the force or the intent that legitimizes it, makes it human and real. My proverbial folk-art self might also be similar to the one that started cutting out paper, although I had a lot of rules and ideas in place for why I wasn’t going to paint. I didn’t have rules in place for why I was going to cut paper.

MH Your work has been compared to satirical work by people like Hogarth and Goya along with Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Colescott, and Adrian Piper. Are there people in other genres that you feel a certain kinship with?

KW Mark Twain is high on the list. I sometimes conjure up imaginary conversations with him about his characters, their frankness. I query him about Huck and Jim and their urgency to survive. I ask if he ever felt disappointed that his political stories were misunderstood as children’s tales, or if he was perfectly jaded by human foibles and certain that “children’s tales” are all we produce anyway.

MH How would you describe your relationship to narrative?

KW Laylah Ali and I were talking not too long ago about how sometimes the word narrative is used in a way that feels very distant. Storytelling has this quality of being folksy and homey and not critically viable. I like storytelling. I like the way people invent things and lie, and construct identities for themselves as a form of storytelling.

MH How did you start using Br’er Rabbit in your work?

KW I worked backwards. The rabbit popped up before I had really sat down and read Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories, and then I got very interested. It wasn’t too long after I had drawn the rabbit that I said, “Hey, that must be Br’er Rabbit.” It’s a rabbit with clothes on, you know.

MH Which is not so common. I didn’t know the whole background of Br’er Rabbit and Br’er Fox before I looked it up—that the two are based on African trickster figures; that “Br’er” was an abbreviation of “Brother,” which is how the slaves addressed one another; and that the stories were collected from slaves at the Laura Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana.

KW I have a collection of the stories, and some of the drawings and engravings I prefer over others. I like the crispness of A. B. Frost’s drawings of wrinkled pants and the expressiveness of these animals running around acting like black men. That’s the strangest part about the stories. That and the idea of ventriloquism. Here is Joel Chandler Harris effectively playing the part of anthropologist: he’s transcribing, but also calling things from his memory. There is something that feels direct, but it is completely indirect in that he creates this cobbled-together mythological creature called Uncle Remus who was a construction of the many servants and slaves that Harris had known in his childhood. Then there is the little boy, who is Harris himself, or maybe he is the entryway for a certain type of reader to inhabit this world. In one of the stories, there are a number of voices: Uncle Remus starts the story, but a mysterious man, maybe West Indian—the accent changes—starts some verbal sparring with Uncle Remus. He corrects Uncle Remus about how the story should go, and it is almost illegible because of how the dialect is transcribed. Then Aunt Somebody Else is off to the side making commentary. You can almost hear it happening, but just when you think you are getting closer to a very familiar, familial scenario, you are pulled back into this white male point of view—a reminder that you are not part of this. It’s an interesting process to move through all of these levels of story to get back to a trickster character. It feels very African. These are not like Aesop’s fables, with a moral at the end.

MH Speaking of fables, you made a limited-edition pop-up book called Freedom: A Fable? A Curious Interpretation of the Wit of a Negress in Troubled Times. I know that you designed it for Peter and Ilene Norton and that it was not intended for children, but the form itself does suggest children as a possible audience. I am wondering if you have had any experience with children seeing your work.

KW Just my daughter, who is my biggest critic.

MH How old is she?

KW She’s nine now, and at the risk of repeating myself formulaically, she did at age four say something along the lines of “Mommy makes mean art.” She still remembers saying that. She comes to my shows. At the Walker, for the first time I felt like censoring my work from her. I didn’t, but it did creep into my consciousness.

MH There are a lot of attempts to mediate people’s reactions to your work: wall text and warning signs. I am curious what an unmediated experience with your work might be like.

KW I don’t know. Children are drawn to the overall clarity of the black figures on white. Then things get pretty murky, because parents come in and explain things and it becomes too much. Too much for the parent, like where do you begin, or do you just let things flow? That’s what I chose to do with my daughter. I had all kinds of anxieties. What negative impact will this have? I just thought, I can’t predict anything, so she will just have to guide me through my work.

MH You create these worlds that are so full of brutality and desire and rape and maiming—umbilical cords and piles of shit and power struggles everywhere. Is there any love in that world?

KW There is all this giving over of self and stealing and taking of others. I think it is born of a kind of passion, but you know how passion can be confused with love and can inspire all kinds of criminal acts. Where is the love? I’m still learning. (laughter) The writing pieces are about that. There is still a part of the activity that is private, and the voice within the writing is still complicated.

MH T. S. Eliot wrote a poem called “The Hollow Men” that reminds me of your work: “Between the idea / And the reality / Between the motion / And the act / Falls the Shadow” and “Between the conception / And the creation / Between the emotion / And the response / Falls the Shadow” and “Between the desire / And the spasm / Between the potency / And the existence / Between the essence / And the descent / Falls the Shadow.” Do any of those “betweens” feel like places that your work resides?

KW All of them. Where the shadows that I’ve been making fall short is that they become solid and I feel like I am still—with the film or projections—trying to find a way to make the between-ness more transparent without being absent.

MH That between place is a state that I am always thinking about. Like F. Scott Fitzgerald saying, “The true test of a first-rate mind is the ability to hold two contradictory opinions at the same time,” or Rilke, “Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves.”

KW That sounds like love right there to me.