Marcelia’s First Paint Party Photo

dj Friday at oh art gallery

Friday at octobergallery gallery 2 12 16

Feb 12 at October gallery

Friday at oh

October Gallery friday

Friday at octobergallery

gallery

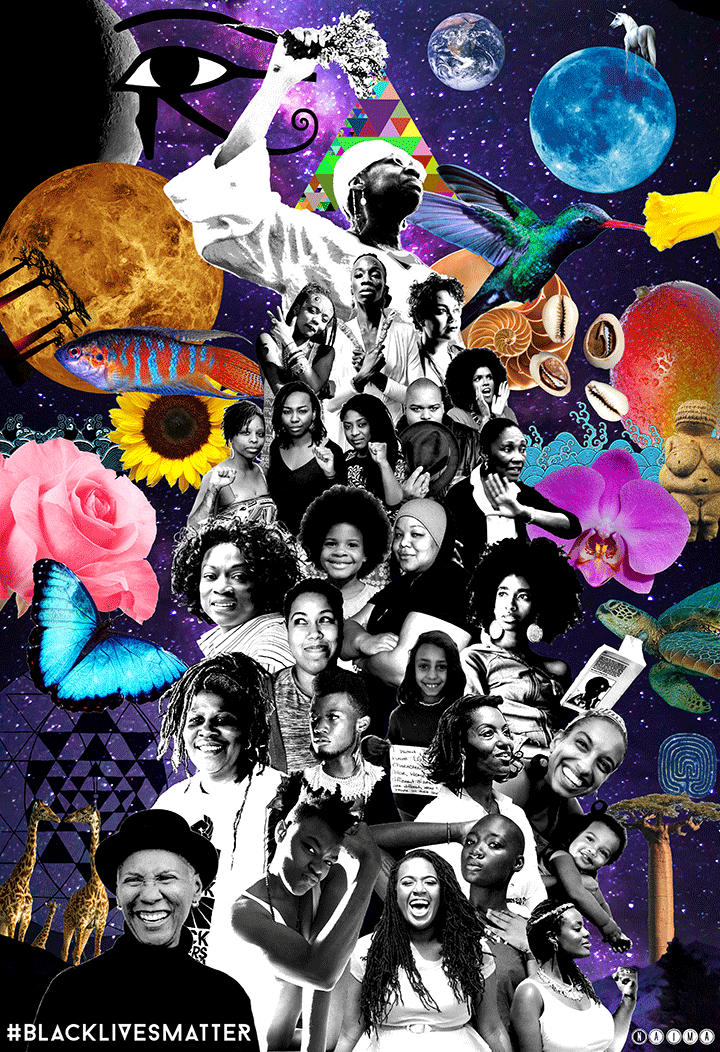

oh what a world we live in by sheila P

sheila black history MLK

Art, dance and more for Black History Month in Seattle

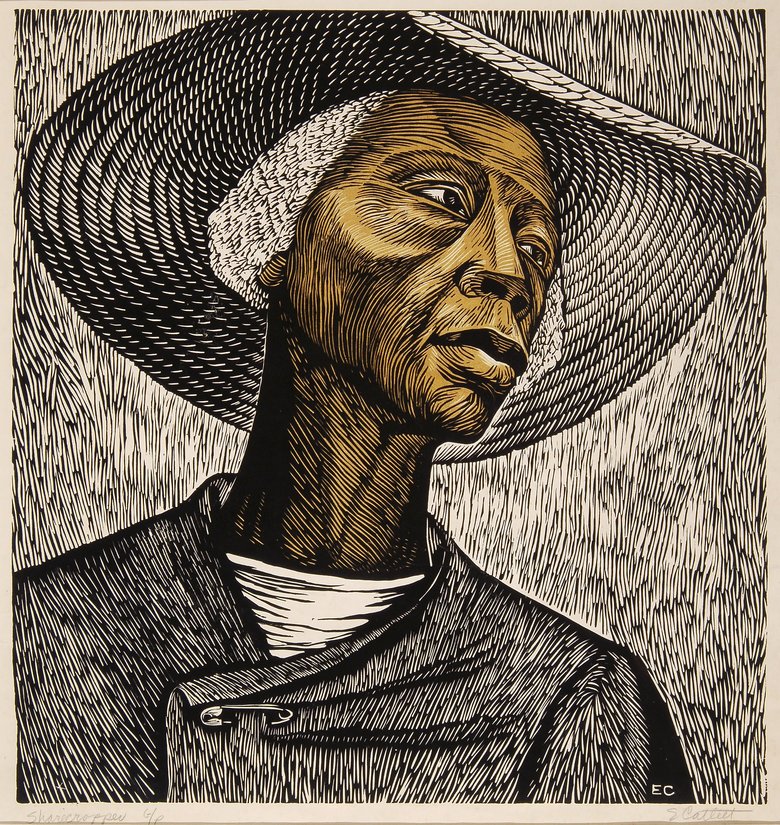

“Sharecropper,” a linocut by Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), is part of the exhibit of works from the Harmon and Harriet Kelley exhibition at the Northwest African American Museum. Many of Catlett’s works reflected the hardship faced by women

“It’s really a very special, rare collection,” said NAAM executive director Rosanna Sharpe. “It’s a survey of the best in terms of works done by African-American artists, and so I like to not say it’s African-American art, but it’s American art done by African-American artists.”

Most art-history books are written by white men, so unfortunately the myriad of women in the arts or artist of color in the larger narrative of American art was overlooked,” she added. “So this exhibit, and a lot of other exhibits, are starting to be more recognized and have started to correct some of the historical wrongs of how American art was authored.”

The pieces are displayed thematically, as opposed to chronologically, around such topics as social commentary, important figures and landscapes. Artists Ron Adams, Margaret Taylor-Burroughs, Henry Ossawa Tanner and Jacob Lawrence, who taught for 15 years at the University of Washington and is the namesake of the school’s Jacob Lawrence Gallery, are included in the exhibition.

For Sharpe, Ron Adams’ 2002 lithograph “Blackburn” particularly stands out.

“It kind of gives the feeling of a professional artist in a printmaking studio doing his craft,” she said. “It speaks to not the professionalization but definitely the studio environment where some of these works were created.”

From Seattle Presents Gallery’s “Sign of the Times” exhibition, created in the aftermath of the Charleston church shooting, to a Northwest Tap Connection performance at EMP Museum, there are ample opportunities across the city to mark Black History Month.

One standout: “The Harmon & Harriet Kelley Collection of African American Art: Works on Paper” at the Northwest African American Museum, through April 17. (The museum is at 2300 S. Massachusetts St., Seattle; admission is $5-$7, more info at naamnw.org.) The 68-work traveling exhibition includes drawings, etchings, lithographs, watercolors and pastels — all by African-American artists, and all part of one of the country’s best collections of such work.

Harmon and Harriet Kelley, of San Antonio, Texas, began buying art after a museum exhibition made them realize how many black artists they were unaware of, and that they wanted their daughters to grow up better informed about their heritage.

The Northwest African American Museum is the only African-American museum between Vancouver, B.C., and San Francisco, said interim communications manager Otts Bolisay, and Black History Month is one of NAAM’S busiest times of the year.

“It’s kind of amazing to see people come through who had no idea that the museum was even there and how thankful they are that we are doing this sort of thing,” he said. “This is a space where the community can feel a sense of ownership and belonging to see these images of themselves.”

The museum will also be hosting teen workshops in March and April for aspiring artists, Sharpe said. On Feb. 24, they will be partnering with the Seattle Art Museum to host “Complex Exchange: Tradition | Innovation,” the first of a series of four events focusing on themes of art, technology and music in relation to blackness, according to Bolisay.

“Seattle really lacks a system by which artists of color are patronized in terms of galleries and exhibit opportunities,” Sharpe said. “We need to do our part to encourage artists who want to do this as a living and creating systems by which artists can be collected, exhibited, researched and documented.

“We want to really bring that force during Black History Month,” she said.

“The Harmon & Harriet Kelley Collection of African American Art: Works on Paper,” at the Northwest African American Museum, features 68 works by prominent black artists. It’s one of several ways Seattle institutions are marking Black History Month.