“There have been the singing nun and the flying nun, but the hippest of all is Los Angeles’s painting nun,” noted Newsweek in its 1967 cover story on Sister Corita Kent, the artist, activist, and teacher, whose first career survey, as The Saratogian reports, opened at the Francis Young Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore college this week.

Corita Kent,

E eye love, 1968, serigraph.

COURTESY OF THE TANG MUSEUM AT SKIDMORE COLLEGE AND CORITA ART CENTER, LOS ANGELES.

Despite her edgy Pop sensibility, influential friends like Ben Shahn and Buckminster Fuller, and posthumous shows in various museums, along with a 2009 exhibition at Zach Feuer Gallery, Sister Corita never became a presence in the mainstream art world. No doubt this is partly because of her vocation (she was a Sister of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, which she joined in 1936 and left in 1968), and the fact that she was a printmaker, rather than a painter.

Corita Kent,

for emergency use soft shoulder, 1966, serigraph.

COURTESY OF THE TANG MUSEUM AT SKIDMORE COLLEGE AND CORITA ART CENTER, LOS ANGELES.

Deploying the earnestness of a believer, an avant-garde sense of typography, and a collagist’s wit, Sister Corita (1918-86) mashed together words and slogans from advertising, the Bible, philosophy, poetry, and lyrics, producing hundreds of confrontational, inspirational prints on themes of individual empowerment and social justice. (Later her 10 rules for Immaculate Heart College’s art department, which cite and are sometimes misattributed to John Cage, became an online classic.)

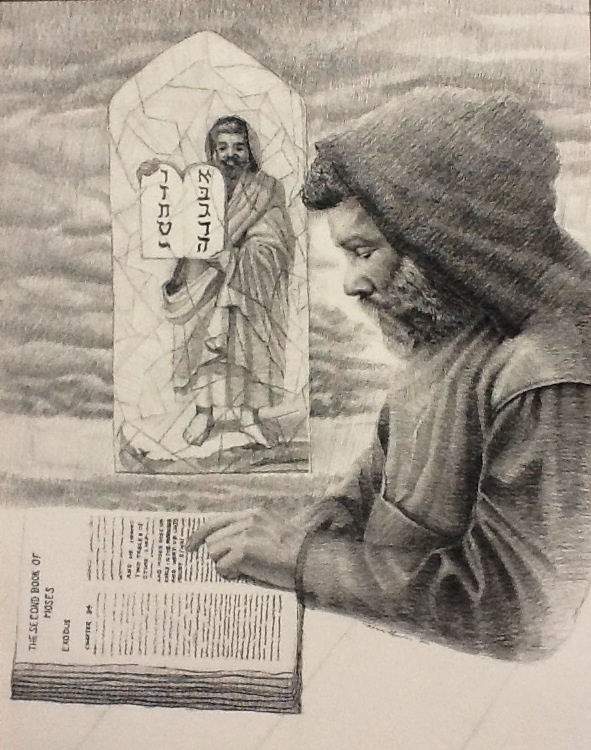

Sister Mary Corita,

king’s dream, 1969, serigraph.

COURTESY OF ZACH FEUER GALLERY, NEW YORK AND THE CORITA ART CENTER

“Almost in some ways she was outsider even though was she trained and was insider in other ways,” says Tang director Ian Berry, who co-curated the exhibition with Michael Duncan. “I’m hoping this show can get her into the trajectory of art conversation.”

Power Authority

More activist art was in the news when the Brooklyn Museum announced its acquisition of 44 rare works from the Black Arts Movement of the mid-’60s to the mid-’70s, landing Elaine “Jae” Jarrell’s stunning patchwork Urban Wall Suit (1969) on the cover of the Times’s Weekend Arts section.

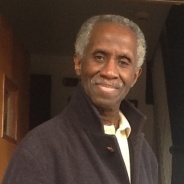

Benjamin “Ben” Jones,

Untitled (Murray), 1973, watercolor, colored pencil, and mixed media collage on board.

GIFT OF R.M. ATWATER, ANNA WOLFROM DOVE, ALICE FIEBIGER, JOSEPH FIEBIGER, BELLE CAMPBELL HARRISS, AND EMMA L. HYDE, BY EXCHANGE; DESIGNATED PURCHASE FUND, MARY SMITH DORWARD FUND, DICK S. RAMSAY FUND, AND CARLL H. DE SILVER FUND, 2012.80.21.

The Black Arts Movement, conceived as the cultural arm of the Black Power Movement, was started by Amiri Baraka. But its manifesto of sorts was written by Larry Neal, who in a 1968 essay in Drama Review, called for “a radical reordering of the western cultural aesthetic” with new “symbolism, mythology, critique, and iconology.”

To convey its message of self-determination and nationhood, the medium of choice for the Black Arts Movement was usually screenprint with a liberal dose of collage, appropriation, and futurism, as evident in works like Revolutionary, Wadsworth Jarrell’s -Day-Glo 1972 portrait of Angela Davis, and Jeff Donaldson’s 1969 rendering of rifle-toting Wives of Shango.

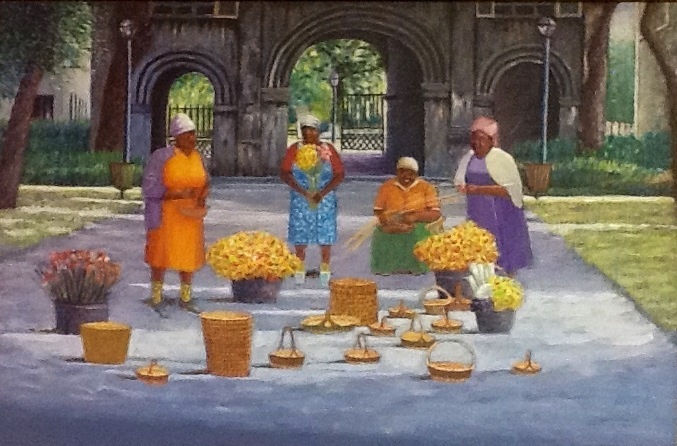

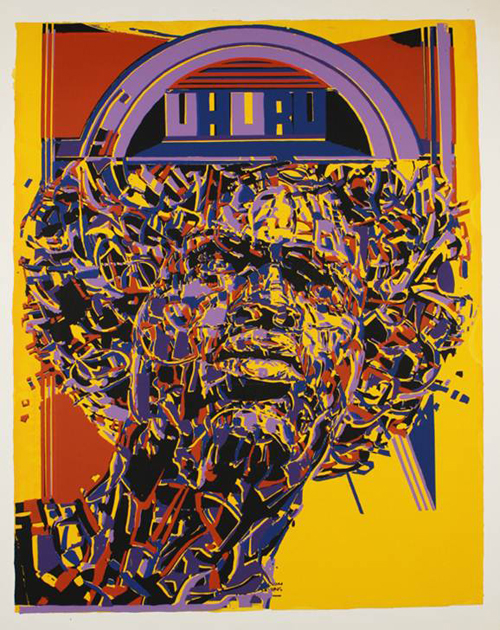

Nelson Stevens,

Uhuru, 1971, screenprint on paper.

BROOKLYN MUSEUM, GIFT OF R.M. ATWATER, ANNA WOLFROM DOVE, ALICE FIEBIGER, JOSEPH FIEBIGER, BELLE CAMPBELL HARRISS, AND EMMA L. HYDE, BY EXCHANGE; DESIGNATED PURCHASE FUND, MARY SMITH DORWARD FUND, DICK S. RAMSAY FUND, AND CARLL H. DE SILVER FUND, 2012.80.41.

That these radically conceived works are entering art-museum galleries–some in the Brooklyn Museum’s American Identities galleries this spring, and others in its upcoming exhibition about the Civil Rights movement next year –shows that the canon of postwar American art has come a long way, kind of.

Fight of the Butterfly

As the activist art of a half-century ago, like the agitprop art before it, enters museum collections, a new generation is developing its own esthetic. Writing in Creative Time Reports, Robert Lovato describes some of the cultural interventions that artist/activists are staging to campaign for migrants’ rights—particularly those adapting the monarch butterfly, that great migrator, as the movement’s symbol.

Alfredo Burgos and Pablo Alvarado,

Migration is a Human Right

COURTESY OF NO PAPERS NO FEAR

That butterfly floats through Migration is Beautiful, a video recently posted on rapper Pharrell Williams’ i am OTHER YouTube channel that’s been making the rounds of blogs. The three-part series follows artists, designers, and performers who have been using the arts to campaign for migrant justice in Arizona, at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, and in actions across the country. A prominent generator of new iconography has been No Papers No Fear, an advocacy group that put out a call for images to express the migrants’ struggle. Many of the artists who responded drew clearly on the precedent of ’60s activist art.

Doing the Rights Thing

One artist who has managed to bring the art of activism into the academy is Cuba-born Tania Bruguera, recently announced as the winner a Meadows Prize residency awarded by the Meadows School of the Arts at Southern Methodist University.

Since she launched Immigrant Movement International as a project cosponsored by Creative Time and the Queens Museum in 2011, Bruguera has offered free classes, workshops, pro-bono legal advice, and other services, operating out of a storefront in Corona, Queens. This year, Bruguera plans to spend more time teaching immigrants art history—“not as an end, but as a means to something else,” she explains, using the imagery as a bridge to approach difficult subjects. Bruguera and her team have also been working to develop a visual arsenal for immigrants’ rights, including a ribbon whose blue and brown tones reflects their passage by land and sea.

Tania Bruguera worked with a group at Immigrant Movement International to create a

Ribbon for Immigrant Respect.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND IMMIGRANT MOVEMENT INTERNATIONAL.

More recently Immigrant Movement produced a rubber stamp to stamp currency with the notice that immigrants pay taxes, too. The image, and the idea behind it, are partly behind a performative event that the group will stage at “How Much Do I Owe You?”, an exhibition organized by No Longer Empty at the Clock Tower in Long Island City on Saturday, February 16, at 2 p.m.

A rubber stamp made by Immigrant Movement International.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND IMMIGRANT MOVEMENT INTERNATIONAL

Copyright 2013, ARTnews LLC, 48 West 38th St 9th FL NY NY 10018. All rights reserved.

Corita Kent, E eye love, 1968, serigraph.

Corita Kent, E eye love, 1968, serigraph.

Corita Kent, for emergency use soft shoulder, 1966, serigraph.

Corita Kent, for emergency use soft shoulder, 1966, serigraph.

Sister Mary Corita, king’s dream, 1969, serigraph.

Sister Mary Corita, king’s dream, 1969, serigraph.

Benjamin “Ben” Jones, Untitled (Murray), 1973, watercolor, colored pencil, and mixed media collage on board.

Benjamin “Ben” Jones, Untitled (Murray), 1973, watercolor, colored pencil, and mixed media collage on board.

Nelson Stevens, Uhuru, 1971, screenprint on paper.

Nelson Stevens, Uhuru, 1971, screenprint on paper.

Alfredo Burgos and Pablo Alvarado, Migration is a Human Right

Alfredo Burgos and Pablo Alvarado, Migration is a Human Right

Cesar Maxit, Migrant.

Cesar Maxit, Migrant.

Tania Bruguera worked with a group at Immigrant Movement International to create a Ribbon for Immigrant Respect.

Tania Bruguera worked with a group at Immigrant Movement International to create a Ribbon for Immigrant Respect.