In assembling his art collection, Barnes outsmarted the world. In crafting his foundation, Barnes outsmarted himself.

Albert Coombs Barnes was a brilliant man. As a student, Barnes emerged from one of Philadelphia’s toughest neighborhoods, eventually earning a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and studying chemistry in Germany. As an entrepreneur, he made a fortune through the mass production of anti-blindness medicine. As a businessman, he timed the sale of his business perfectly, selling at the peak of a surging market. As an art enthusiast, he amassed one of the world’s finest collections of post-Impressionist and early modern paintings. As a philanthropist, he created a school—not a museum—where some of the world’s finest works of modern and post-Impressionist painting were studied in strict accordance with Barnes’ self-designed pedagogical principles.

All in all, the same brilliance that created a legacy for Albert Barnes would ultimately undo his legacy. Since the time of Barnes’ death in an automobile accident in 1951, the Barnes Foundation has been a case study in how an institution, created by a brilliant mind with clear intentions, can become irrevocably damaged through overly restrictive operating guidelines, unanticipated leadership problems, and the competing missions of other organizations and institutions. Much attention has been paid to the forces at work against the foundation, but in fact the seeds of destruction were sown by the hands of Barnes himself. As history has proven, decisions he made in life imperiled the perpetuity of his collection after death.

Barnes made every effort to preserve the vision of his creation after his death. For the past 60 years, what we have seen at the Barnes is what Barnes put there himself. At this moment, however, Barnes’ art collection is being removed forever from the walls he built for it. Barnes knew he was creating something unique in the annals of American art. He was also right that outside forces would emerge to alter his project after his death. What he never anticipated was that the very defenses he put in place to preserve his collection would eventually contribute to its undoing.

Lincoln’s Leadership

In September 1988, a bedridden, 89-year-old Violette de Mazia gave up the ghost. She had outlived Barnes by 38 years, throughout which time she had faithfully guarded the foundation. With her departure, the board faced a succession challenge. Leadership would devolve to people who never knew Barnes. Once again, the protocols Barnes implemented—in a document that he revisited and revised many times—proved a serious impediment to carrying out his overall intent.

In Article IV of the original 1922 bylaws of the foundation, Barnes detailed the mechanisms whereby new members would be nominated to the board following the death of himself and his wife. The first vacancy was to be filled by election of a person nominated by whichever financial institution was then treasurer of the foundation. Subsequent nominations would be made by the board of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the board of the University of Pennsylvania. In other words, three different nominating bodies would fill vacancies on the board. Those bodies would then have the power to nominate candidates for those seats in perpetuity, rotating and balancing power among themselves.

Those plans finally came undone in the spring and summer of 1950, after Barnes exchanged a series of increasingly insulting letters with Harold Stassen, the newly installed president of the University of Pennsylvania, whom Barnes decreed was “what psychologists term a ‘mental delinquent,’ variously known to laymen as a ‘dumb bunny, false alarm, phony.’” Barnes had clashed with his alma mater before, but now was committed to removing it from the future of his foundation.

On October 20, 1950, less than a year before he died, Barnes amended the foundation’s indenture. “No Trustee,” he wrote, “shall be a member of the faculty or Board of Trustees or Directors of the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, Bryn Mawr, Haverford, or Swarthmore Colleges, or Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.” Instead, following the nomination of a member submitted by the financial institution, the amendment codified that, “the next four vacancies . . . shall be filled by election of persons nominated by Lincoln University, Chester County, Pennsylvania.”

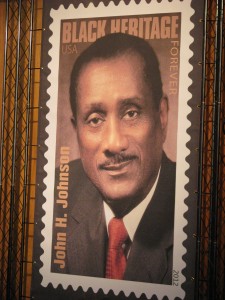

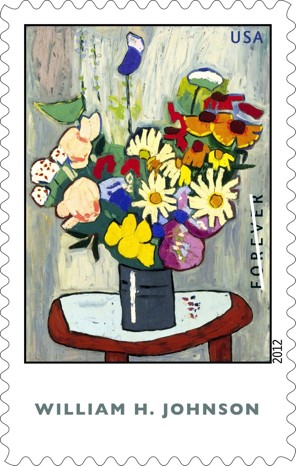

When Barnes gave Lincoln the authority to nominate four of the foundation’s five trustees, it was a testament to his progressive attitudes on race. Lincoln was a small, historically black university, whose graduates included Thurgood Marshall, Langston Hughes, and Cab Calloway. Late in his life, Barnes had become close to Horace Mann Bond, the president of Lincoln who also happened to be the father of the civil rights leader Julian Bond. When the elder Bond invited Barnes to lecture on art (for $9.25 per hour) during the 1950–51 school year, Barnes was “so overwhelmed with joy and admiration,” he wrote back, “that I danced the cancan.”

The amendment would radically change the future of the Barnes Foundation. Curiously, Barnes never informed Lincoln of his plans; the school learned of the change in 1959, and then by accident, eight years after Barnes had died. Perhaps Barnes believed that the strength of his indenture, just like the power of his collection, did not require an expert to comprehend. In any event, the Lincoln that Barnes knew in the 1940s was not the same institution in the 1980s, by which time it was a faltering state-subsidized school. Its leadership was not always as inspired as Bond’s, nor was Barnes’ foundation as financially strong in the 1980s as it had been in 1950.

Within a few years of Lincoln gaining control of Barnes’ nominating process, a politically connected lawyer by the name of Richard Glanton was elected president of the Barnes Foundation. Glanton, an African American from a small, Appalachian town in Georgia, was, like Barnes, a self-made man with a fearless, combative will. Unlike Barnes, Glanton was outgoing, Republican, and very much interested in belonging to Philadelphia’s innermost elite circles. Handsome, charming, and ferociously ambitious, Glanton could not have been more dissimilar from the studious and withdrawing de Mazia. Even more different would be how they ran the Barnes Foundation. Where de Mazia sought to preserve the Barnes in its 1950s state, Glanton was eager to institute a wide range of changes.

Glanton immediately pointed to the foundation’s run-down physical plant, combined with the weakness of its endowment, and argued the need for breaking the Barnes indenture. Initially, he planned to sell off items in the collection. In November 1990, he petitioned the Montgomery County Orphans’ Court for permission to deaccession $15 to $18 million worth of paintings. After a heated public outcry, the board voted down Glanton’s plan in June 1991. But Glanton was more successful in his second effort, convincing the Pennsylvania courts to allow the foundation to send the art collection on an international tour, to publish a glossy catalogue of the collection, and to open the institution to paying crowds. All of these moves were widely criticized by Barnes’ students—and expressly forbidden by Barnes’ indenture.

But, facing a depleted endowment, Glanton argued, they were necessary. These activities, however controversial, raised much-needed revenue. In August 1992, he convinced the court that, while the Cret building was closed for renovations, it would make sense to take some 80 items on a one-time worldwide tour, with stops scheduled in Paris, Tokyo, Toronto, Washington, Fort Worth, and—to cap it off—the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In all, the tour netted some $16 million for the foundation. While the paintings were off the walls, they generated enough money to pay for the $12 million overhaul of the Cret building, and left another $4 million for the slowly growing endowment.

Glanton was not satisfied. Even after the success of the tour—over 30 months, some 4.5 million people had viewed the traveling exhibit—it was not clear how the foundation could continue to raise operating income. Glanton proposed increasing the admissions fee (to $10) and tripling the number of annual visitors (to 120,000). In order to do so, the Barnes Foundation would need to expand its parking lot. Neighbors on Latch’s Lane were already uneasy with the proposed expansion, but they objected strenuously to adding parking. Glanton sued, invoking federal statutes designed to break up the Ku Klux Klan. He accused neighbors of “thinly veiled racism,” and pushed hard to get them to buckle. Glanton believed the lawsuits would settle early, but when they dragged on for years, costing the foundation over $6 million and further eroding the endowment, they began to call into serious question the viability of the Barnes.

Glanton’s tenure as president of the Barnes came to an end in February 1998, when he was ousted, four votes to one, by his fellow board members. From Glanton’s proposal to sell major artwork to his breathy charges of racism, his continued leadership became untenable. His endless litigation had weakened Barnes’ already fragile endowment. He had departed from the indenture on several key points—taking items from the collection on a worldwide tour, publishing a glossy catalogue, and working to make the Barnes into a partially self-funding enterprise—thereby alienating those most dedicated to Barnes and his legacy. But whatever else may be said of him, and whatever his motivations, Richard Glanton was in complete harmony with Albert Barnes on one key point. Both men were devoted to the independence of the Barnes Foundation.

All in all, the crises of the Lincoln years were the consequence of decisions that Barnes had made years earlier. Barnes’ 1922 bylaws ensured checks and balances on board nominations, with alternating entities nominating different seats. Under the 1922 rules, no single entity nominated a majority of the foundation’s board members. The 1950 amendment did away with this balancing mechanism, meaning that Lincoln effectively controlled four of the five seats. The fate of the Barnes Foundation became irrevocably linked to the health of one other organization—one which, for all of its historic strengths, was never properly acquainted with the demands of administering an art school and art collection, even in Barnes’ lifetime.

read more…..

Like this:

Like Loading...