As a complement to Road to Freedom, The Bronx Museum will also present AFTER 1968: Contemporary Artists and the Civil Rights Legacy. This smaller exhibition includes works from seven African-American, emerging artists and collectives—all born on or after 1968—who have created new work examining the heritage of the Civil Rights Movement and its affect on the lives of this new generation. Using the movement as inspiration, context or critique, these artists address their own personal understanding of race, identity, American violence, and political activism providing new perspectives on and discourse about this critical time in history.

Avisca Art Show 7/9-7/31 Atlanta

Samella Lewis and Jimi Claybrooks Video

Dr. Samella Lewis, Visual Artist and Jimi Claybrooks

This was a video conference at the Philadelphia International Art Expo. October Gallery. In 2000 October Gallery produced a video conference with artists Dr. John Biggers and Dr. Samella Lewis. This video conference was part of the annual Philadelphia International Art Expo.

Watch Video

Is Black Art Still Relevant? Video

Is Black Art Still Relevant?

Watch Video

Informal discussion on, Is Black Art Still Relevant in 2010.

African American Art.

Participants include: Gaille Hunter, John Williams, Elizabeth Nelson McCorkle, Evelyn Redcross, Aria Jones, Stan Burwell, Thaddeus Govan, Jr., Martina Johnson-Allen and Tanya Murphy.

Filmed at October Gallery Germantown, PA. May 9, 2010

Watch Video

Ghana High Fashion Madonna by Cal Massey

Ghana High Fashion Madonna by Cal Massey

Original on Canvas

Size: 30 x 48 Approx

About the Artist:

MOORESTOWN-Cal Massey said that the wonderful images that appear on his canvases come to him during his daily meditations. He jots them on notecards and stores them in a filing cabinet that stands near the easel in his studio. “Everything in my work is spiritual,” the 80-year-old artist said. Entering the artist’s home/gallery studio on Dawson Street is almost a spiritual experience in itself. Messiah, a rendition of a black Christ as one with the earth, standing between the galaxies and the oceans, is the first painting a visitor notices. Near it hangs “Angel Heart”, which Massey considers one of his most popular works, inspired in part by the lack of black angels in traditional artwork. The angel’s hair, styled in a full Afro, is a tribute to the natural beauty of the black woman, Massey said. For years, Massey’s work has represented the black community in the art world. Now the artist, whose work already hangs on the walls of Congress members and rock stars, will see his work hang from the necks of Olympians. Massey was one of 13 artists from around the world chosen to design a commemorative medal for the 1996 ,Summer Olympics in Atlanta.

Untitled Study by Lois M. Jones

Untitled Study by Lois M. Jones

Lois Mailou Jones (November 3, 1905 – June 9, 1998) was a prize winning artist who lived into her nineties and who painted and influenced others during the Harlem Renaissance and beyond during her long teaching career. She was born in Boston, Massachusetts and is buried on her beloved Martha’s Vineyard in the Oak Bluffs Cemetery.

Dr. Jones began painting as a child and had shows of her work when she was in high school. “Every summer of my childhood, my mother took me and my brother to Martha’s Vineyard island. I began painting in watercolor which even today is my pet medium.”

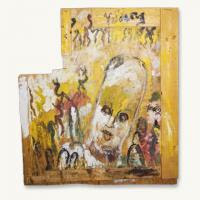

The Artwork of Purvis Young

Miami Artist Purvis Young Dead at 67

We have just learned from one of Purvis Young’s lifelong friends that Purvis passed away this morning in Miami.

Purvis had just turned 67 on February 4th of this year.

Those of us who had the privilege of being his friend know that a “ great soul “ has been taken from us. Purvis Young was a true and consummate artist who lived entirely for his art. He leaves behind a colossal body of work which has already given pleasure to countless people who have seen it in the over sixty museums in in which his vibrant expressionistic paintings have been shown.

Purvis Young will live on through his paintings and in the memory of his friends and myriad collectors.

more………………

49er Vernon Davis an artist at heart

By Peter Hartlaub, Chronicle Pop Culture Critic

When Vernon Davis does finally get to the Sistine Chapel, he’ll be a little closer to the “Creation of Adam” than most visitors. At 6 feet 3 and 250 pounds, the pass-catching tight end definitely stands out in a crowd.

Tonight the San Francisco 49er with the heart of an artist hopes to pass on his message to kids, headlining the first Art Impact speaker series at the Koret Auditorium in the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, followed by a fundraiser for the Vernon Davis Visual Arts Scholarship Fund at Morton’s Steakhouse.

The Art Impact series is a joint effort from the San Francisco Arts Commission and the San Francisco Unified School District. Davis spoke with us last week from Washington, D.C., where he lives in the offseason.

A Great Day (and Night) in Harlem

By DAVID YEZZI

By DAVID YEZZI

New York

Not long before Romare Bearden’s first major museum retrospective opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971, he peered out from a friend’s window overlooking Lennox Avenue in Harlem and made a few small sketches. The friend was the writer and critic Albert Murray, and the sure-handed, vibrant drawings—made with an array of brightly colored felt-tip pens—became the basis for Bearden’s iconic collage “The Block,” a series of six panels depicting low-rise buildings and storefronts on a single block between 132nd and 133rd Streets. “The Block,” along with a clutch of preliminary sketches, is now on view for a limited time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bearden, who succumbed to bone cancer in 1988, was a master draftsman and painter (whose line and palette sometimes recall Matisse), but it is his prismatic collages of blacks in America, populated with evocative elliptical narratives, for which he is best remembered. The pasted-paper compositions adorning the Masonite fiberboards of “The Block”—originally connected horizontally, now individually framed and preserved behind glass—show a cross-section of African-American life and culture north of 110th Street: apartments, stoops, a church, a barbershop, a liquor store, a funeral home.

Bearden’s buildings barely contain the teeming life within them, as figures composed of paint, colored and metallic paper, fabric, and cut-up photographs and Photostats spill out onto the sidewalks. Bearden’s subject is not, finally, bricks and mortar but experience. As he explained at the time: “When I sketched this block, I was looking at a particular street, but as I translated it into visual form it became something else. I lost the literalness and moved into where my imagination took me.” Bearden envisions—often through mullioned windows or cut-away sections of facade—lovemaking, worship, children at play and, more fantastically, an Annunciation and angels carrying a haloed figure aloft. We see lovers kissing, a homeless man sleeping, a hunched figure sitting alone.

Bearden looks past the buildings themselves to “the lives they contained within their walls.” Behind brick exteriors, a figure reclines in a bathtub as, a few windows down, another rises awkwardly from a bed. Bearden allows us to peer into living rooms and kitchens, each one populated with distinct characters and each with a story to tell. (All six panels are bracketed from below by gray slabs of street and from above by sky blues alternately day-lit and crepuscular.)

Bearden’s Cubist-inflected compositions draw inspiration from modernist masters such as Picasso and Braque (both of whom he met in Paris while studying at the Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill in the ’50s). But Bearden Americanized Cubist collage and made it his own, bringing to the medium his signature brand of storytelling. Harlem is where Bearden grew up and where he eventually had a studio. His genius for gesture and (often autobiographical) anecdote infuses his work with a personal emotional charge, while his formal control allows his domestic scenes to be intimate without becoming corny. As the playwright August Wilson, who owed a great debt to Bearden, put it, “From Romare Bearden I learned that the fullness and richness of everyday ritual life can be rendered without compromise or sentimentality.”

Like his friend the painter Stuart Davis, Bearden was passionate about jazz (he co-wrote the hit song “Sea Breeze,” recorded by Dizzy Gillespie). The jazz techniques of call and response and serial improvisation and variation find a visual corollary in Bearden’s work: He likened his shapes to the spaces between the notes. Rhythm provides the key to Bearden’s work. “The Block” takes its life from the energetic interplay of colored rectangles and the curves introduced by cut-paper figures, lampposts, architectural ornament, letters, clouds. Note, for example, the procession of yellow disks as they recur in the work, appearing first as a halo, then as either a sun or moon glimpsed above the rooftops and through a bedroom window, then in a scene on TV, and finally as the light atop a barber pole.

Color creates another dynamic rhythm in Bearden’s work. Bearden was a commanding colorist: the faded passages of painted paper—muted and rubbed blues, purples, browns and sea greens—make palpable the grit of pavement and old brick. Within his deftly colored structures, Bearden distills action and character with breathtaking economy and energy—whether the figures are running, recumbent, limping or laughing. The results are frequently surprising: a child nearly enveloped by the enormous hands of his father, the huge face of a heavy-lidded boy looking out from behind a half-lowered shade.

If Bearden is now not as widely renowned as his Pop contemporaries, it may be the fault of his abiding seriousness. While artists after Warhol succumbed increasingly to the siren-song of irony and kitsch, Bearden remained true to his modernist vision, to tradition and continuity. As the critic Hilton Kramer noted, Bearden makes use of forms that “derive originally from African art, then passed into modern art by way of Cubism, and are now being employed to evoke a mode of African-American experience.” Bearden was serious about his inheritance and about what he bequeathed. As one percipient reviewer put it, Bearden “is not playing games. With a gentle sympathy, he explores his culture and our culture with the delicate sensuality of a good physician feeling for broken bones.”

Part of the Met’s collection since 1978, “The Block” is a work of permanence and affective power. But it can only be seen for another two weeks before it heads back to storage. Because of the fragile nature of “The Block”—composed largely of pasted paper susceptible to fading—it tends to be shown for only a few months at a time, every five or so years. It is worth a special trip just to see it.

—Mr. Yezzi is executive editor of The New Criterion. His latest book is “Azores: Poems.”

Disaster Relief: David Bates’ Katrina Paintings

|

Disaster Relief: David Bates’s Katrina Paintings

Reviewed by Steve Shapiro

Disasters ask nothing of humans; catastrophe on any scale, whether natural or man-made, happens without the expected equation. The aftermath is always a realm of possibilities—some, like large-scale war, are easier to transform into art (Goya’s “Disasters of War” etchings; Picasso’s “Guernica”); others, like the Hindenburg explosion or the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, seem to exist as they are. No artistic response is made or available for healing. There is no rule of thumb when considering a disaster.

To the classic examples of disaster art—Goya’s etchings, Picasso’s painting—I nominate David Bates’s oeuvre, in pencil, charcoal, watercolor, photography and painting, in response to the Hurricane Katrina upheaval of 2005. Katrina’s total destruction will never be quantified; its aftershocks continue to this day. The artistic challenge for a disaster unfolding in real time, on TV and in so many other twenty-first century formats, is to make the art both timely and timeless.

Photographs and video are the most immediate, and many photographs, such as Debbie Fleming Caffery’s black and white pictures of the area, leap out at the viewer in the way only photography can. (Think of the image of Jack Ruby shooting a handcuffed Oswald: a painting of the same scene would lose the specific intensity.)

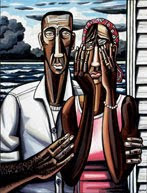

David Bates, an African-American born in Dallas, watched the event on TV and he says that something hit him: he understood he was witness to a tragedy of Biblical proportion—indeed, history was literally being washed away. As he began to formulate sketches from images on television and in photographs, a project on the scope of “Guernica” took hold. The forty-plus paintings and works in other mediums, at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art (until August 22), is the most riveting show I can recall in months. Bates’s vision fills the Kemper’s rotunda; yet for all the sadness and ache the show records, the work is electric, alive to the idea that art is the nearest thing we have to being in someone else’s shoes.

The works are primarily portraits, with some galvanizing still lifes of streets underwater or neighborhoods ravaged (“Tennessee Street I” depicts a car tossed against a tree, with mangled junk everywhere). The show opens with sketches of faces and heads on yellow lined school paper and small photos that will be enlarged in oil on canvas later. One of the most powerful images is entitled “Mother and Child”: an oversized woman holding onto her baby rises up out of floodwater with the city behind her, like a mythic creation. Another work, of several boatmen, recalls the ferryman Charon rowing departed souls through the Underworld’s river Styx. But modern catastrophes create their own myths. In Bates’s work, while there are hints of the Pièta and other iconography (the marvelous oil portrait “The Flood, 2006-7,” of a an older black couple, is modeled after Grant Wood’s sobering “American Gothic” and feels like a new version), mostly the art is defined by itself. The portraits looking back at the viewer express everything with nothing extra needed.

Bates’s men and women have a distinctly Picassoid appearance: the Cubist set of the brow and the eyes and the nose makes for distinctive portraiture. The sitters are not alike, however. Each person, though the titles may be generic (“Katrina Portrait III”), exudes his own identity and suffering (and humanity, too). When Picasso began the sketches for what would emerge as “Guernica” he kept changing the compositions; for example, he moved the wailing women holding her child, now seen on the left, from the other side, where the writer Russell Martin believes she now has some protection from the bull. Picasso saw the work like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel artwork: as of a piece. Such works do have an impact, a laser-like drawing together of the visual and the emotional.

In Bates’s Katrina work, rather than compacting figures for an enormous singular piece, he introduces person after person after person in separate portraits in oil, watercolor and charcoal; the variety of agony—some women hold their hands to their faces in despair, some look fierce, others forlorn—extends and enlarges the anguish and the confusion. The sense of displacement in these peoples’ lives, though they are anonymous to us are no less vivid.

And when Bates does his own “Guernica”—entitled “The Storm”—he jams several dozen people into three oversize canvases: it acts like a culmination of all the individual portraits at the Kemper. Someone is wiping away a tear; another has a hand over her mouth. Each person has something about himself to catch the viewer’s eye. It brings to mind not only Picasso but also Diego Rivera’s folkloric murals of the people and the land—here, though the people, abandoned by their local and national governments, have been packed like sardines into the unhealthy, unsafe Louisiana Superdome.

No poem, Auden once wrote, ever freed anyone from a concentration camp; true, but that is no reason not to try. Art like David Bates’s Katrina portraits offer some relief from a form of extreme disaster that neither the artist nor the politician nor the spiritual leader can prevent or protect us from. The artist’s contribution may be scant, but for many people without a voice to be heard or a face to be seen it can be an act of mercy. Contrition is someone else’s business.

AfroSolo Theatre Co Presents AFROSOLO ARTS FESTIVAL 17

San Francisco’s award-winning AfroSolo Theatre Company presents the 17th annual AfroSolo Arts Festival, celebrating African American artists giving voice to the Black experience. This year’s theme, UNITED IN PEACE: Artists, Clergy, Legislators, and Community, promotes the power of peace through live performances, the visual arts, and other events to envision and celebrate peace. This year’s Festival not only pays homage to and explores the rich legacy of African Americans and people of African decent, it also focuses on a coming together of all people for The Common purpose of peace. Festival events (July 29-October 15) featuring live music, visual art, and works for the stage will take place in San Francisco at Yerba Buena Gardens, the Main San Francisco Public Library, the African American Art and Culture Complex, and the Ella Hill Hutch Community Center. Most events are free and open to the public.

The line up for AfroSolo 17 is as follows:

The Arts: A Medium for Peace

A Panel discussion in collaboration with The Commonwealth Club of San Francisco

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Reception: 5:30pm; Panel discussion: 6-7pm

San Francisco Commonwealth Club (595 Market Street, SF)

Tickets: $12 members, $20 non-members

From the iconic peace sign to singer/songwriter John Lennon‘s “Give Peace A Chance” to AfroSolo Artistic Director Thomas Robert Simpson‘s solo performance piece There Is No Hatred Here, artists throughout the years have used art as a medium to promote peace. The Commonwealth Club joins AfroSolo Arts Festival 17 in hosting a lively discussion about using art to envision, promote, and celebrate peace, examining the role the arts have played in peacemaking movements of the past and present. Acclaimed Bay Area poet, novelist, and playwright Jewelle Gomez moderates this panel, featuring Brad Erickson, Executive Director of Theatre Bay Area, Michael Morgan, Conductor and Musical Director of the Oakland East Bay Symphony, and Ariska Razak, Dancer/Choreographer and Program Chair of the Women’s Spirituality Department at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

A Concert for Peace

Outdoor Jazz Concert in Yerba Buena Gardens

Saturday, August 7, 1-4 pm

Yerba Buena Gardens (Mission Street between 3rd & 4th, SF)

Free and open to the public

In collaboration with the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, AfroSolo presents its ninth free concert in the Gardens. This year’s offering features the Junius Courtney Big Band Orchestra. A 19-piece multicultural band noted for it swinging interpretations of Duke Ellington and Count Bassie classics, original compositions, and Latin jazz works, the Junius Courtney Big Band Orchestra was founded in 1966. After the passing of Junius Courtney at the age of 88, son Nat Courtney became the bandleader, under the musical direction of George Spencer. Sharing the stage will be incomparable vocalist Denise Perrier, who has performed for over 30 years throughout the Bay Area, Europe, Latin America, and Asia.

Performance for Peace

Sunday, August 8, 3-5:30 pm

Performance Space TBA

Tickets: $35-100

AfroSolo hosts this exciting multicultural, cross-cultural, and intercultural performance showcase. Actors, dancers, musicians, poets, and performers representing different cultures and backgrounds emphasize the bonds that we all share in performances highlighting compassion, understanding, joy, and peace. Performers TBA

Visual Artists for Peace

Visual Arts Exhibit

Sunday, August 15 – October 15

(Artist Reception August 15, 3-5pm)

Main San Francisco Public Library (100 Larkin Street at Grove)

Free and open to the public

AfroSolo presents a visual art exhibition showcasing works from African American artists and artists from the African Diaspora, exploring the theme of peace. This multi-media group show includes paintings, sculptures, ceramics, photography, and cartoons. Artists TBA.

UNITED IN HEALTH

Artists, Healthcare Workers, and Community

Saturday, August 14, 10 am – 2 pm

Ella Hill Hutch Community Center (1050 McAllister Street at Webster, SF)

Free and open to the public

In collaboration with Supervisor Ross Mirkarimi, MoMagic, the African American Health Disparity Project, St. Mary’s Hospital, California Pacific Medical Center, and Kaiser Permanente, AfroSolo hosts this free community health fair.

TICKETS:

Most events are free and open to the public, unless otherwise noted. For tickets and more information, the public may visit afrosolo.org or call 415-771-AFRO (2376).

Funding for the AfroSolo Theatre Company is made possible in part through the support of the African American Health Disparity Project, California Arts Council, Friends of AfroSolo, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, LEF Foundation, San Francisco Grants for the Arts/Hotel Tax Fund, The National Endowment for the Arts, Yerba Buena Gardens Festival and the Zellerbach Family Foundation.

Presenting Partners: African American Art & Culture Complex, The Commonwealth Club, San Francisco Main Public Library, and Yerba Buena Gardens Festival.

Frederick Hayes & Ernest Jolly

Please join Patricia Sweetow Gallery for an exhibition with artists Frederick Hayes and Ernest Jolly. Frederick Hayes, Cityscape: Drawings, Installation and Paintings, includes serialized small format drawings in groups of 4 or 8, charcoal drawings and acrylic paintings. Ernest Jolly will present an installation with video, sound, and sculpture, Just Off Shore. read more

Gantt and McColl Centers Unite to Highlight Culture and Diversity Initiatives

CHARLOTTE, NC.- Through the creation of a shared Creative Director position, Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture and McColl Center for Visual Art have taken a historic first step to formalize their relationship. This new partnership unifies and amplifies their voices in the community, while strengthening the organizations’ shared-interest in leading diversity and art education initiatives with an emphasis on community engagement with the arts and artists.

“Art has a natural way of bringing people and ideas together,” says Suzanne Fetscher, President and CEO of McColl Center for Visual Art. “We are proud to be partnering with the Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture. This alliance is a natural extension of the educational and programming initiatives that we are both doing – showcasing how art and artists can be used as catalysts for social advancement.”

Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture and McColl Center for Visual Art are forging an agreement that will enhance the strengths of both institutions. Starting on July 1, 2010, Ce Scott, presently Director of Residencies and Exhibitions at McColl Center for Visual Art, will become Creative Director for both arts organizations. Scott will lead this endeavor by solidifying the relationship and immediately launching joint programming. “It is an honor for me to share my creative vision and leadership with both organizations,” said Scott.

“This partnership has extraordinary possibilities,” says David Taylor, President and CEO of Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture. “We are living in a global community and arts education is a powerful tool that can foster and promote cultural awareness. Our commitment to working with McColl Center will also allow us to leverage the uniqueness of both organizations, create the Gantt Center ’s artists-in-residence program and enhance our education and outreach programs.”

Both organizations are supported by the Arts & Science Council. “The Arts & Science Council is pleased to see these important cultural organizations collaborating to reach a broader audience and serve the community,” said ASC President Scott Provancher.

Scott has been employed at McColl Center for Visual Art since before its opening a decade ago. She is originally from Detroit , Michigan , and has an MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art. She is an artist and educator and has exhibited her work regionally and nationally as well as served on local and national cultural arts boards. She joined Fetscher to launch educational programs at the fledgling artist colony envisioned by CEO of Bank of America, Hugh McColl, Jr.

Since those early days, the Center has grown to become nationally renowned for its artist-in-residence and other program offerings. The Center ranks among the top three artist-in-residence programs in the nation according to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

In October 2009, Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-Arts + Culture, named for former Charlotte mayor and business leader Harvey Gantt, opened its new facility at the South Tryon Street Cultural Campus. The Gantt Center has promoted African-American art and its influence on American culture for the past 35 years. They offer a variety of cultural experiences, including visual arts, performance, film, literature and education outreach.

The Gantt Center will welcome their first artist-in-residence, Fahamu Pecou, an Atlanta-based artist whose work seeks to expose stereotypes of African-American masculinity reflected in contemporary media. Pecou will be co-located at the McColl Center for Visual Art this fall.

Another yet-to-be-named Gantt Center artist-in-residence will be selected for McColl Center ’s winter session. Both Pecou and that artist will be featured in a joint exhibition of work created while in residence at McColl Center for Visual Art at the Gantt Center in summer 2011. Both the residencies and exhibitions will be key to education and outreach experiences, including summer children’s camps shared between the organizations.

The organizations have worked together in the past leading up to this formal relationship. Several artists associated with the Gantt Center have been artists-in-residence at McColl Center for Visual Art, including San Francisco artist Willie Little, Chapel Hill’s Juan Logan and Atlanta-based Michael Harris, a professor at Emory University who is presently a curatorial consultant with the Gantt Center . The Gantt Center and McColl Center for Visual Art are also investigating the possibility of developing an artists-in-residence international exchange program to promote African outreach efforts.

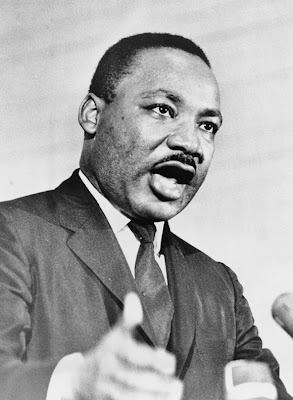

Decisions on MLK memorial raise debate

Decisions on MLK memorial raise debate

Decisions on MLK memorial raise debate

Last Modified: Sunday, June 6, 2010 at 1:06 a.m.

Work progresses on a memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., while a Boiling Springs granite sculptor and supporters continue pushing for more American artists and sculptors to be involved.

Clint Button and Georgia artist Gilbert Young hope to persuade members of the National Memorial Project Foundation to get rid of the King sculpture made by an artist in China. They also want all of the granite for the $120 million monument to come from America instead of having pieces shipped from China.

Spartanburg African-American leaders are interested in the campaign because they have a bond with the slain civil rights leader. King preached one of his first sermons at the local Mt. Moriah Baptist Church in the late 1940s, and his uncle, the Rev. Joel L. King, was the pastor of that church.

“There are so many African-American artists who could have done the statue,” said City Councilwoman Linda Dogan. “I think it is absolutely justified to get American artists. When an artist does a work, they have to have an intimate knowledge of the subject. If they don’t, you will see it in the work.”

Dogan, an art major in college, said a good candidate for the project is South Carolina’s Mac Arthur Goodwin, who was instrumental in building the African-American History Monument on the grounds at the Statehouse in Columbia.

“I don’t understand where they (foundation members) are coming from,” Dogan said.

Rep. Harold Mitchell, D-Spartanburg, said the memorial is a worthwhile project, but doesn’t like the idea of sending work outside of the country when thousands of people are looking for work and the national unemployment rate is 9.7 percent.

Collard Greens Museum explores black history

Charlotte — It’s called the Latibah Collard Green Museum. But the small museum on Cullman Avenue isn’t about greens or cooking. It’s about one man’s dream.

Both the dream and the museum are the work ofT’Afo Feimster, an artist, playwright and activist who co-owns The Art-House, a collection of studios and display spaces at the end of a street of warehouses a few blocks from the NoDa gallery district.

In a city that has exploded with new cultural institutions, from the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art to the NASCAR Hall of Fame, Feimster’s little museum is something different, a small collection of scenes he created to illustrate black history.