By KEN JOHNSON

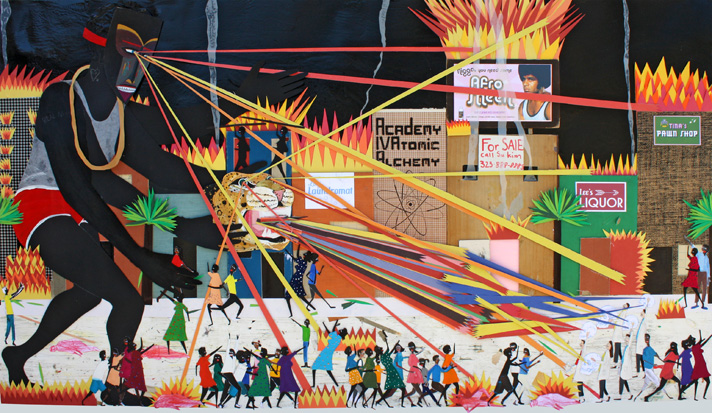

There is a paradox at the heart of “Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles 1960-1980,” an exhibition at MoMA PS1 about black artists who lived and worked in Los Angeles during a time of revolutionary changes in art and society. It is not specifically addressed by the exhibition, which was organized by Kellie Jones, a Columbia University art historian, and had its debut at the Hammer Museumlast year as part of the Californian extravaganza “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980.” But I think it goes some way toward explaining why so few black artists have been embraced by the predominantly white high-end art world. It has to do with the relationship of black artists to Modernist tradition and the differences between the lives of blacks and whites in this country.

The first piece you encounter on entering the exhibition, a welded-steel construction by Melvin Edwards called “August the Squared Fire” (1965), is emblematic. It consists of an upright rectangular framework within which a concatenation of twisted, bent, boxy forms is held, as if frozen in the moment of tumbling through a door or window. Formally, you have a dialogue between stasis and dynamism, and psychologically, between reason and feeling.

Such dualities would be enough on which to base judgment and interpretation were this a piece by, say, the white junk sculptor Richard Stankiewicz. But it makes a difference to know that Mr. Edwards is African-American and has for decades been producing small, wall-mounted assemblages of industrial steel parts called “The Lynch Fragments,” a few of which are in the show.

There is the allusive title “August the Squared Fire” to consider too. The most violent episode of civil unrest in the city’s history up to that time happened in the predominantly poor and black neighborhood of Watts in August 1965. So Mr. Edwards’s sculpture can be read as a metaphor for the struggle of black people to break through barriers that have kept them down in America.

The Watts uprising was galvanizing for other artists in the exhibition, among them Noah Purifoy, whose densely compacted assemblages of found materials are like the children of a Dadaist and an unhinged folk artist. According to Ms. Jones’s catalog essay, Mr. Purifoy has said that the Watts calamity made him an artist. He and the fellow assemblagists John T. Riddle Jr. and John Outterbridge began to make sculptures using rubble and detritus left in the aftermath of the riots.

Ms. Jones writes, “Purifoy, John Riddle and John Outterbridge reinterpreted Watts as a discursive force, emblematic of both uncompromising energy and willful re-creation, using the artistic currency of assemblage.”

Herein lies the paradox. Black artists did not invent assemblage. In its modern form it was developed by white artists like Picasso, Kurt Schwitters, Marcel Duchamp, David Smith and Robert Rauschenberg. For these artists assemblage was an expression of freedom from conservative aesthetics and parochial social mores. It did not come out of anything like the centuries-long black American experience of being viewed and treated as essentially inferior to white people. It was the art of people who already were about as free as anyone could be.

Thanks to white artists like George Herms, Bruce Conner and Ed Kienholz, assemblage was popular on the West Coast in the 1960s. Appropriated by the artists in “Now Dig This!,” however, it took on a different complexion. It became less a playful messing with habitual ways of thinking, à la Dada and Surrealism, and more an expression of social solidarity.

Mr. Riddle’s “Untitled (Fist)” (1965), for example, is in the form of an old shovel standing on its handle, its business end cut and bent into the form of a clenched hand. This is a far cry from Duchamp’s snow shovel titled “In Advance of the Broken Arm.” Duchamp’s work is a piece of deracinated, intellectual mischief-making designed to question relations between language and reality. Mr. Riddle’s is about a particular population of people digging itself out of a real-world debacle.

If I am right that most of the work in “Now Dig This!” promotes solidarity, then this poses a problem for its audience. It divides viewers between those who, because of their life experiences, will identify with the struggle for black empowerment, and others for whom the black experience remains more a matter of conjecture. Those who identify may tend to respond favorably to what those viewing from a more distanced perspective may regard as social realist clichés, like the defiant fist.

There are some black artists who finesse the difference, David Hammons being a brilliant example and, tellingly, the only artist in this show to be lionized by the mainstream art establishment. He is a Duchampian trickster who toys in surprising ways with signifiers of black culture, poetically unsettling entrenched representations of blackness on both sides of the racial divide.

For me, the exhibition’s most beautiful work is “Bag Lady in Flight,” which Mr. Hammons first made in the 1970s and recreated in 1990. It consists of grease-stained brown shopping bags cut and folded into pleats fanning up and down like wings, the whole extending horizontally almost 10 feet. Pleats along the lower right edge bear triangles of nappy hair, forming a pattern like that of a bird’s wing. It is an ancient notion that angels might reside in the most degraded of human forms, one that Mr. Hammons here updates to inspiring effect. You don’t have to be black to feel that.

Black artists who have gained recognition in the high-end art world have operated in the Hammonsian mode. Robert Colescott, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Adrian Piper, Fred Wilson, Glenn Ligon, Kara Walker and Jayson Musson, a k a Hennessey Youngman, are some who complicate how we think about prejudice and stereotyping. The art of black solidarity gets less traction because the postmodern art world is, at least ostensibly, allergic to overt assertions of any kind of solidarity. Covert solidarity of liberal white folks? That is another story.

“Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles 1960-1980” runs through March 11 at MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, at 46th Avenue, Long Island City, Queens; (718) 784-2084, momaps1.org.

Like this:

Like Loading...