Born Chloe Anthony Wofford, in 1931 in Lorain (Ohio), the second of four children in a black working-class family. Displayed an early interest in literature. Studied humanities at Howard and Cornell Universities, followed by an academic career at Texas Southern University, Howard University, Yale, and since 1989, a chair at Princeton University. She has also worked as an editor for Random House, a critic, and given numerous public lectures, specializing in African-American literature. She made her debut as a novelist in 1970, soon gaining the attention of both critics and a wider audience for her epic power, unerring ear for dialogue, and her poetically-charged and richly-expressive depictions of Black America. A member since 1981 of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, she has been awarded a number of literary distinctions, among them the Pulitzer Prize in 1988.

Madonna to sell Fernand Leger painting worth over $5 million to support girls’ education

The pop diva puts her philanthropic hat on and parts ways with the ‘Three Women at the Red Table’ piece she’s owned for more than 20 years.

Madonna is parting with an abstract French painting she’s owned for more than 20 years to support educating girls in Afghanistan, Pakistan and other countries. It’s expected to bring $5 million to $7 million.

Fernand Leger’s “Three Women at the Red Table” will be offered May 7 at Sotheby’s auction house. All proceeds will benefit the Ray of Light Foundation.

The pop diva says she wants “to trade something valuable for something invaluable” in countries where female education is rare or nonexistent.

She purchased “Three Women” at Sotheby’s in 1990.

Leger created the work in 1921 as part of a series depicting women with still-life compositions.

Other examples from the series are in the Dallas Museum of Art and the Beyeler Foundation in Switzerland.

Halle Berry lashes out at paparazzi, restrains fiancé Olivier Martinez in airport altercation

The photogs swarmed the couple as they descended a Los Angeles Airport escalator with Berry’s daughter, Nahla

Halle Berry has no tolerance for paparazzi when daughter Nahla is around, and on Monday night she turned into a mother grizzly, lashing out at photographers hounding the Oscar-winning actress and her family at a Los Angeles Airport.

“Get out of the way!” Berry is heard saying in a video obtained by TMZ. “It’s a child!”

Berry, 46, has been vocal in the past about her disdain for the shutterbugs, even supporting a measure that would ban paparazzi from taking unauthorized photos of celebrity children.

The photographers swarmed Berry, her daughter and fiancé Olivier Martinez as they descended an airport escalator and made their way to a waiting SUV.

At one point Martinez tries to retaliate against one photographer in the intense paparazzi gang by kicking, but is quickly restrained by Berry, who tries to get everyone in the car safely.

It doesn’t stop there: The paparazzi even try peering into the car with their cameras as it drives away.

October Gallery Art Expo 2011

Bring Back the Afro (Video)

By Simon Doonan

She was the baddest one-chick hit squad to ever hit town. The freak with the ’fro. I’m talkin’ ’bout Miss Sweet Brown Sugar With a Touch of Spice. A sistah with drive who don’t take no jive. I am talking about the Vanessa-muthafuckin’-Redgrave of Blaxsploitation movies. Have no fear, Pam Grier is here.

You’ll have to excuse my profanity. I recently spent an entire week YouTube-ing Pam Grier’s ’70s oeuvre. By the time I was done, my brain had absorbed the raw rhythms and bad-ass expletives of ’70s black street culture. Now it’s virtually impossible for me to engage in conversation without suddenly calling someone, anyone, a dumb-ass jive turkey, and such.

My Grier research had a purpose. I scored an interview with Miss Grier at the opening of last month’s Pam Grier retrospective at the New York Film Society, and I really wanted to have my shit together, man. You dig? So I made my way through Black Mama, White Mama; Greased Lightning; Foxy Brown; and the rest. It was a life-changing experience. Miss Grier, the first blacktress to headline as an action star, was a taboo-busting screen goddess. Her specialty? Thanks to her outdoorsy Huck Finn childhood, the fearless Pam could fire a gun without blinking. I also have to admit that I came away with a rabid and renewed appreciation for that luscious afro.

In Scream, Blacula, Scream, Pam’s ’fro is short and tight and neat as a pin. In Coffy, it’s longer and more dandelion-shaped. In both instances it is an object of beauty, even when there are razor blades nestling in its recesses.

As I watched Pam machine-gunning her way to cult superstardom, I recalled the other afro-queens of yore: Remember Marsha Hunt—the original cast member of Hair, the icon of playbills and posters, and the co-creator, with Mick Jagger, of a child she named Karis? And then there were the Black Panther afro-activists like Angela Davis and Kathleen Cleaver. Kathleen, wife of Eldridge, was a loud and proud afro-advocate, who accessorized her ’fro with hoop earrings and giant sunglasses.

I remembered fash-fro queens like Pat Cleveland and stylish songbirds like Minnie Ripperton (mother of Maya Rudolph), whose signature flourish was to augment her teased hairdo with sprigs of baby’s breath.

The afro had it all: It was natural, symbolic, regal, unisex, and glamorous. Liberated from the costly and time-consuming burden of trying to make their hair resemble that of white folk, black chicks—and dudes—had found the perfect marriage of style and practicality. And yet … styles change, and fashion evolves, and the afro has—with the exception of occasional retro-hipster sighting on Broadway below Eighth Street—become as rare as a dodo.

It is impossible to imagine Beyoncé or Kerry Washington or Michelle Obama rocking a Pam Grier afro today (though Beyoncé paid a retro-camp tribute to the style in the 2002 Austin Powers movie). The alternatives—$2,000 weaves, time-consuming blowouts, and scalp-searing chemical processing—seem infinitely less desirable, and yet, African-Americans have largely turned their backs on the freaky ’fro. But what does this honky know?

During the course of my on-stage conversation with the inspirational Pam, the subject of coiffures came up repeatedly. La Grier, who on this gala occasion was wearing her hair in a silky high-lit, marcel-waved waterfall, was more than happy to talk wigs and weaves. When I expressed my longing for the return of the afro, Pam was quick to splash a little reality on my nostalgic longings. According to Lady Grier, it’s not as low-maintenance as it looks.

Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images

The most difficult challenge occurs upon waking. The act of sleeping wreaks havoc on the dandelion perfection of that carefully picked afro. As Pam pointed out, “You go to sleep looking gorgeous, and you wake up and it’s all flattened on one side like a brick wall.” According to Pam, “No amount of picking is going to pull it out. You need to take a garden rake to that shit.”

Also, the weather is not your friend: “You are walking down the street thinking you be looking so fly, so cool, and the wind comes up and suddenly you all flat up the backside of your head, lookin’ like a crazy person.”

Pam’s words did nothing to dampen my afro-ardor. I take comfort from the fact that style is a cyclical mutha and that everything comes back into fashion, eventually. The current global obsession with pin-straight hair will run its course, and the afro, and maybe even the jewfro, will return in all its glory.

Thanks to the current unpopularity of the afro, afro picks can be purchased at rock-bottom prices. I recently paid $10 for a box of a 50 from a beauty supply store in Harlem. These objets d’art make great gifts and can be used to tweak and tease non-afro coiffures. The grooviest picks have a Black Power fist in place of a handle. The revolution is coming, and it will be YouTubed. So get your pick now and start practicing.

The Misguided Campaign to ‘Bring Back the Afro’

When is a compliment not really a compliment? When is praise not really praise? Here’s a hint: When you’re a white man reminiscing about the good old days, when black people wore Afros. Yeah…no. Talk about reducing something complex to something simple.

Yesterday on Slate, Simon Doonan posted a piece titled “Bring Back the Afro.” He’d recently spent time watching Pam Grier movies on YouTube in advance of interviewing her, and felt a mix of nostalgia, admiration and awe for her hairdo, writing:

In Scream, Blacula, Scream, Pam’s ‘fro is short and tight and neat as a pin. In Coffy, it’s longer and more dandelion-shaped. In both instances it is an object of beauty, even when there are razor blades nestling in its recesses.

Doonan went on to mention ’70s icons like Marsha Hunt, Angela Davis and Kathleen Cleaver, and waxed longingly:

The afro had it all: It was natural, symbolic, regal, unisex, and glamorous. Liberated from the costly and time-consuming burden of trying to make their hair resemble that of white folk, black chicks-and dudes-had found the perfect marriage of style and practicality. And yet … styles change, and fashion evolves, and the afro has-with the exception of occasional retro-hipster sighting on Broadway below Eighth Street-become as rare as a dodo.

RECORD SCRATCH. Doonan lives in New York, where a veritable ton of people are embracing natural hair, be it a TWA (teeny weeny afro) or a larger, fluffy ‘fro. From Harlem to Clinton Hill and Fort Greene and beyond, natural hair is all over this town. Not to mention being celebrated on NPR and online, on sites like Le Coil, Curly Nikki, Natural Hair Rules, and Black Girl Long Hair. Hell, there was a SXSW panel about natural hair. And if you’re not paying attention to the regular people around you, what about the famous folks?

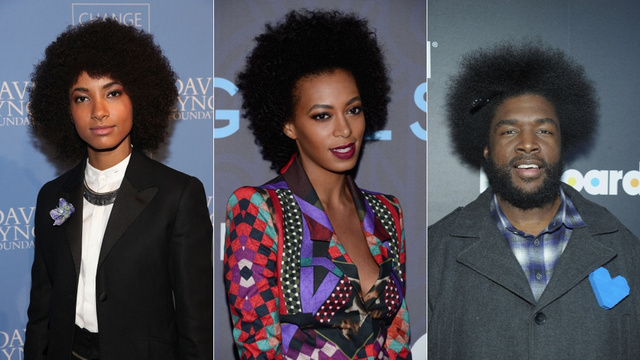

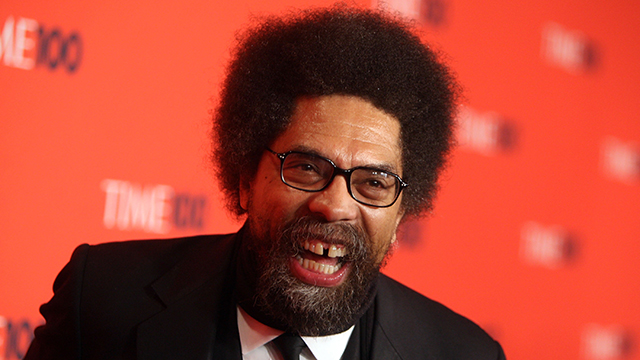

Fairly well-known: philosopher/academic/activist/author Cornel West, who graduated from Harvard in 1973 and earned his PhD. at Princeton. Grammy-award winning musician Esperanza Spaulding, personally selected by President Obama to play the Nobel Peace Prize Concert. Solange, DJ/singer/sister of Beyoncé. Ahmir Khalib Thompson, aka Questlove, drummer/music journalist/producer who plays with The Roots on TV every damn night. All with afros. Rare as a dodo? The dodo is extinct. So not quite. Doonan also bragged that he’d bought a box of Afro picks. How exotic.

The post generated quite a bit of noise on Twitter, with NPR’s Gene Demby sighing that Doonan was “describing human beings like David Attenborough on [the] Nature channel.” Demby took a few jabs at Doonan, while insisting.

But above and beyond quibbling about how popular natural hair is now (because the answer is: VERY, and there are Afros EVERYWHERE, even the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue), the problem with Doonan’s piece is that he genuinely thinks he’s being nice by praising the afro. Is he allowed to think it’s a cool hairstyle? Absolutely. But a white man asking black people to wear their hair in a way that pleases him? That’s not right. Doonan is unaware of his privilege, and not taking into account how deeply political and culturally charged black hair is.

When he writes:

It is impossible to imagine Beyoncé or Kerry Washington or Michelle Obama rocking a Pam Grier afro today (though Beyoncé paid a retro-camp tribute to the style in the 2002 Austin Powers movie). The alternatives-$2,000 weaves, time-consuming blowouts, and scalp-searing chemical processing-seem infinitely less desirable, and yet, African-Americans have largely turned their backs on the freaky ‘fro. But what does this honky know?

Beyoncé wore an Afro wig. And she has done big, curly hair. Kerry Washington had a pseudo-fro in Save the Last Dance. Michelle Obama has been discussed and discussed and discussed, and you know what? It’s fair to doubt that the President would win an election if his wife had an afro. Imagine the headlines, the conservatives, the speculation. She’s been called militant the way she is and her bangs are news. The truth is that hair sends a message. What it comes down to is this: While black people have made great strides, we are still dealing with a lot of deep racism, discrimination and intolerance. Black women have been denied jobs for having dreadlocks. There is still an unspoken consensus that straight hair is seen as more professional. It’s easy and understandable that a man who deals mainly with aesthetics would want to gush about Afros, he’s right: They’re awesome. But what a black woman does with her hair is deeply personal and fraught with meaning.

Ultimately, the problem is that when Simon Doonan wants black people to “bring back the Afro,” he’s ignoring the fact that it never really went away, and also acting as though an Afro is an accessory you can pick up in a boutique, like a turban or some platform heels. It’s not. It’s not even just a hairstyle. It’s so much deeper than that. For many, the process of going natural — from the tough decision to do The Big Chop to transitioning is daunting, especially in a culture that fetishizes long, silky-straight (or ever-so-slightly wavy) tresses. In Western society, our standards of beauty remain rather narrow, and the examples we hold up in magazines and on movie screens generally have straight or straightened hair. Black women who opt for natural hair do so with while being bombarded with messages that straight is better, and that black hair, in its natural state, needs fixing. Let’s not forget how Don Imus infamously called the Rutgers women’s basketball team “nappy-headed hos,” making a connection between hair and promiscuity; you’ll also hear stuff like her hair is wild, unruly, she needs to “tame” that frizz, etc. While Gabby Douglas was competing in the Olympics, viewers criticized her hair‘s lack of smoothness. Consciously or unconsciously, black hair is considered savage by those who don’t have it and those who have been taught to hate it. Chris Rock’s documentary Good Hair shed some light on how black women have been convinced that their hair is not good enough the way it is. Is it any wonder that blow-outs and flat-irons and weaves are popular when women who are considered the epitome of beauty — Victoria’s Secret models — all have long, shiny hair?

It’s fantastic when black women decide to go natural and/or wear an Afro, but Doonan should realize that for many, it’s not simple and it’s not easy. Picking out a fro is not for everyone, and not every hair type can make a good Afro. Even after Pam Grier tells him how difficult the upkeep was for her — “You go to sleep looking gorgeous, and you wake up and it’s all flattened on one side like a brick wall… No amount of picking is going to pull it out. You need to take a garden rake to that shit” — Doonan remains insistent that “the current global obsession with pin-straight hair will run its course.” That would be nice. But you know, in the ’70s, the Afro was a statement, linked to the civil rights movement and a reaction to oppression and the pressure to assimilate. Today’s true ideal situation should not be about one particular style coming back, but about black women (and men) feeling free to do whatever they choose with their hair — and not being pressured to conform or doing it because a white man approves and thinks it’s cool.

Bring Back the Afro [Slate]

Louvre Gets New Leader, Jean-Luc Martinez, A Greek Antiquities Expert

PARIS — France’s Louvre museum is getting a new director – the man who is leading the restoration of its most famous Greek sculpture and has his hands in some of the institutions latest efforts to expand its reach.

Jean-Luc Martinez, a French specialist in Greek, Roman and Etruscan antiquities who has worked at the Louvre since 2007, was appointed by President Francois Hollande for a three-year term.

Martinez, 49, is leading the restoration of the famed headless Winged Victory of Samothrace this year and has been involved in the new Louvre branch in the eastern city of Lens, as well as the museum’s expansion in Abu Dhabi.

He takes over in mid-April from Henri Loyrette, who held the post for 12 years.

Santigold ‘Disparate Youth’ Off ‘Master Of My Make Believe’ (VIDEO)

Most of the world knows Santi White by the name Santigold, her stage name, and the title of the 2008 debut album that got everyone talking. Now it’s the Philly-born singer’s upcoming album that’s making headlines. Coinciding with the NYT premiere of the cover art for the May 1 album Master Of My Make Believe, is the release of Santi’s second video off the album: an island adventure for the single “Disparate Youth.”

The drowsy track features a mix of synth, reggae beats and a title that knowingly or not calls out the respected names working on Master — in this case, Dave Sitek of TV On The Radio, whose acclaimed debut album was Desperate Youth, Bloodthirsty Babe. The video itself is as different from the earlier-released “Big Mouth” as it could possibly, with muted colors and an actual plot. Here Santi treks through a “Lost”-like landscape in search of enlightenment, which she may or may not find after encountering the painted boys of an island tribe. The single drops April 9. Take a look below.

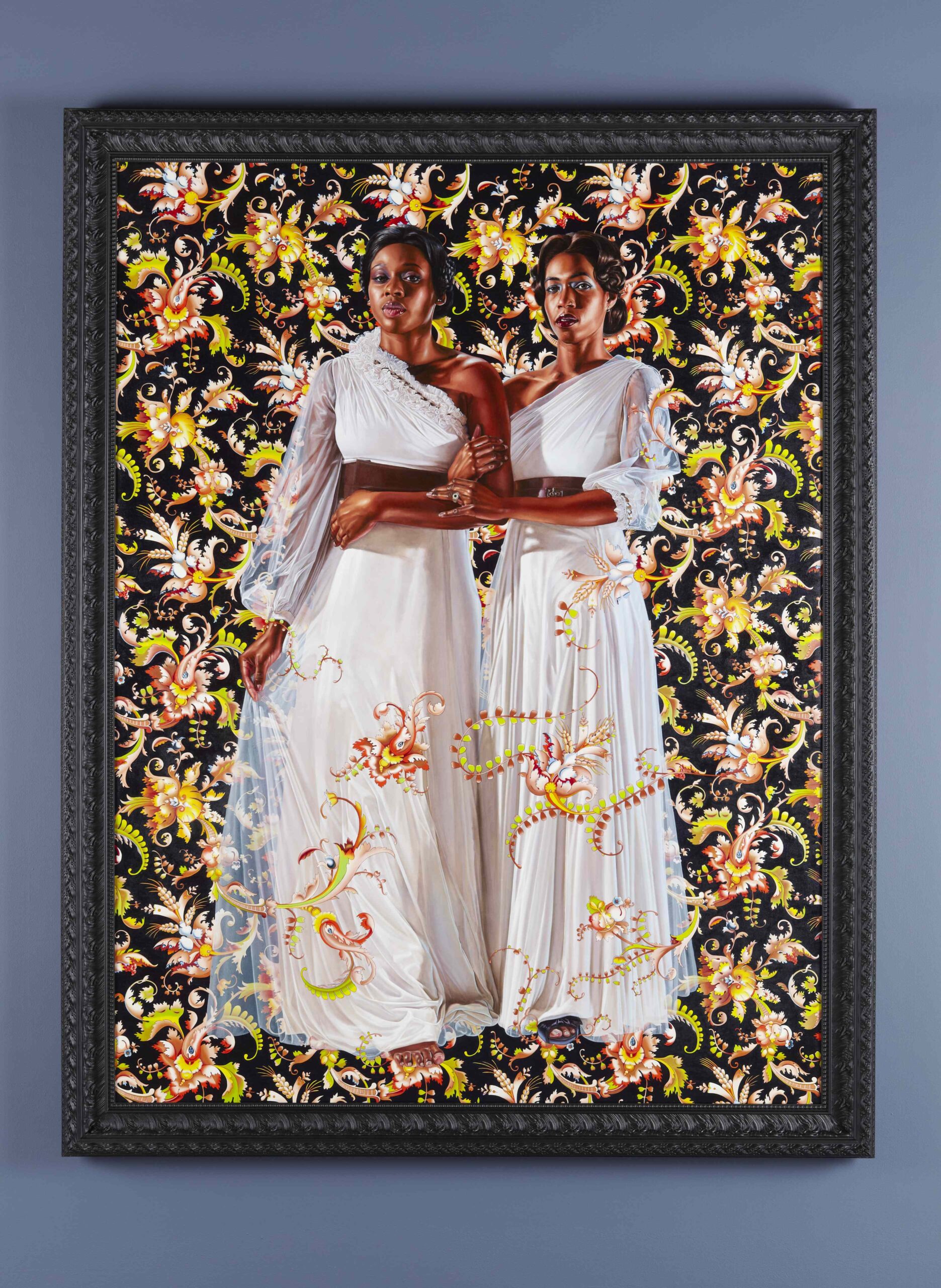

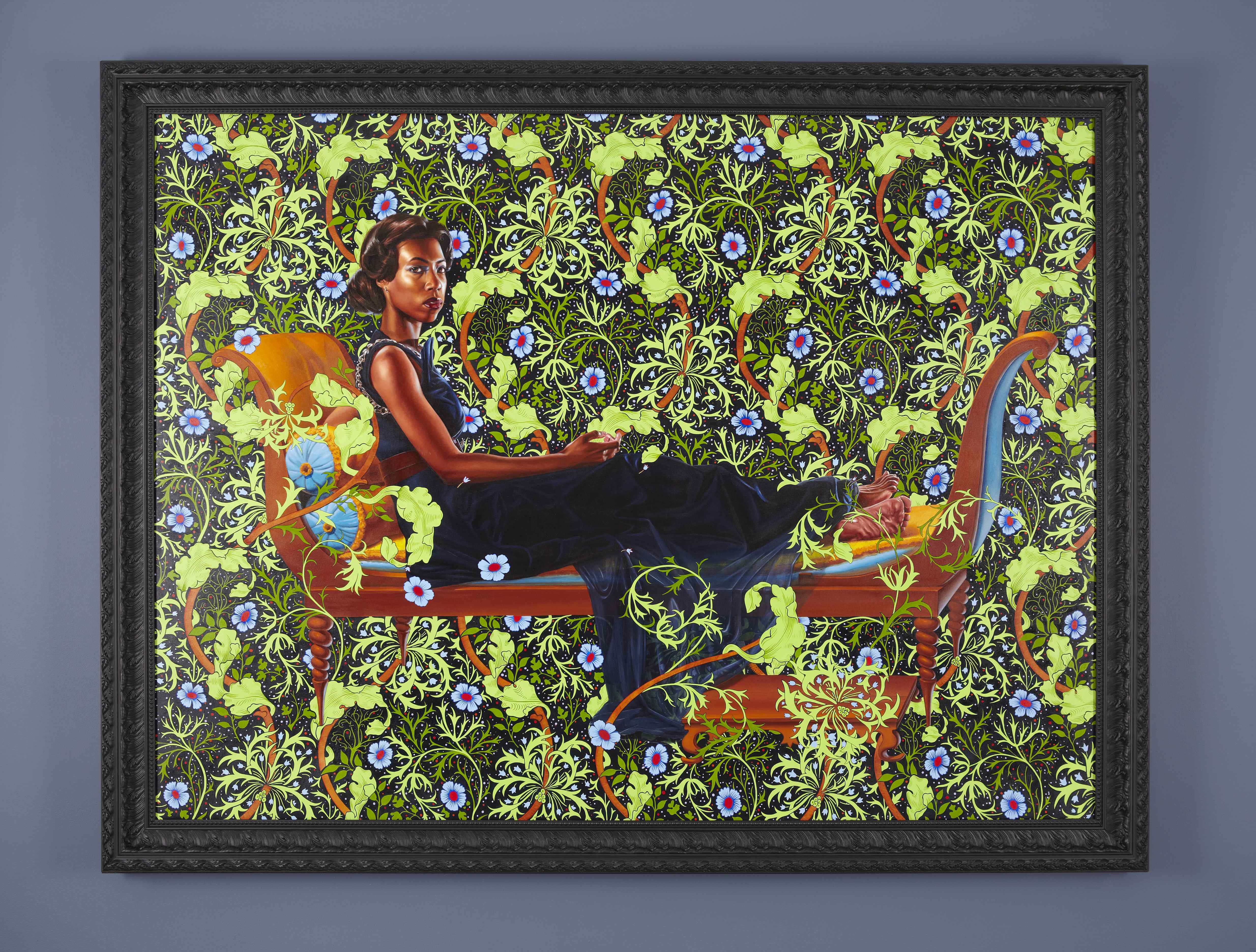

Change: On Kehinde Wiley’s ‘An Economy of Grace’ at Sean Kelly

Bobby Elliott

Writer living in New York City

On the surface, “An Economy of Grace” at Sean Kelly (528 W. 29th) is a well-timed game-changer for painter Kehinde Wiley. After making a name for himself by exclusively painting men, “An Economy of Grace” presents Wiley’s first series of portraits featuring women. For those who have not yet seen Wiley’s work, you might want to spend Saturday, June 2nd catching up on the painter’s career without paying a penny — the Brooklyn Museum, which has a good group of Wiley’s earliest portraits, and the Jewish Museum, with his recent “World Stage: Israel” paintings, will both be free on June 2nd, and Sean Kelly, despite its museum-quality shows, is always free. If you only have time for one show, see “An Economy of Grace,” which will go down as a significant moment in Wiley’s career.

For the past decade or so, Kehinde Wiley has been making evocative, questioning and powerful portraits of men of color from around the world. It began with his portraits of young African American men from New York City and grew into an ongoing, diasporic series known as “The World Stage,” featuring men from China, Dakar, Lagos, Brazil, India, Sri Lanka and now Israel. The same formula he used in those paintings he uses again in “An Economy of Grace” — photo-realist portraiture of models in classical, art-historical poses, set against decorative and colorful backdrops. The defining difference here comes in his choice of subject, all African American women from New York City. Other than that, very little has changed. Should it?

For the past decade or so, Kehinde Wiley has been making evocative, questioning and powerful portraits of men of color from around the world. It began with his portraits of young African American men from New York City and grew into an ongoing, diasporic series known as “The World Stage,” featuring men from China, Dakar, Lagos, Brazil, India, Sri Lanka and now Israel. The same formula he used in those paintings he uses again in “An Economy of Grace” — photo-realist portraiture of models in classical, art-historical poses, set against decorative and colorful backdrops. The defining difference here comes in his choice of subject, all African American women from New York City. Other than that, very little has changed. Should it?

That question can really be asked of all of his work. If you do get to the Brooklyn Museum, one qualitative difference you will find between those early examples of his portraits and his most recent work, is how much Wiley has improved as a painter (especially since 2003s “Go,” a ceiling-mural on the fourth floor of the museum). At the Jewish Museum and at Sean Kelly, Wiley has perfected his touch to such a degree that the paintings appear photographic. And while the jury’s still out on his “World Stage” paintings, the general feeling about the series was that it successfully brought about a larger vision in Wiley’s work; with each successive part, be it the Brazilian portraits or the Chinese portraits, Wiley overcame whatever compositional repetition ensued, with memorable and enjoyable images of young men from around the world, typically marginalized, now celebrated and united.

If Wiley’s career up until “An Economy of Grace” is any indication, the 12 paintings at Sean Kelly are likely to be only the beginning of a very long exploration of femininity, race and power. Instead of painting the women in their everyday clothing, Wiley’s subjects wear dresses designed by Riccardo Tischi, the Creative Director of Givenchy. As in previous paintings by Wiley, many reference specific portraits and paintings — Jacques-Louis David’s “Madame Juliette Recamier,” the many renditions of Judith and Holofernes (here, Wiley’s has painted Judith as an African American woman holding the head of a white woman) and John Singer Sargent’s “Mrs. Waldorf Astoria,” among them. You don’t need to know any of those paintings to get the general idea: Wiley is reappropriating past images to create new ones, with the intent of empowering his subjects. To that end, I wish I had gone to “An Economy of Grace” with a woman, to hear her reaction to the portraits and their resonance, a reaction more important than my own.

For those new to Wiley, these portraits will delight. They are characteristically fun, acrobatically good and meaningful, the colors are great — all of these things I felt myself. For those who are looking for daring new heights in Wiley’s career, what could have been a great departure for the artist does end up feeling staid. Some of the portraits are flatter than others, and I do believe that Wiley needs to start pushing compositional boundaries a bit more, especially as he explores the subject of femininity. When indifference is the farthest emotion Wiley is looking to incite, it’s hard not feel like we are back to square one, this time with women instead of men. This series, too, begins where his first portraits began, New York City, and here, the excitement is quieter and the drama less original. Notably missing from these paintings is the sexuality of his male portraits, which juxtaposed domineering masculinity with uncanny delicacy and tenderness — a feat on view at “World Stage: Israel.”

But if this is the beginning of a new frontier for Wiley, one that he will engage over this next decade, “An Economy of Grace” may be happily modest in its first steps. Although prolific — all of these paintings were made in 2012 — Wiley is an artist that takes his time and one that has always found ways to make things interesting. Will there be a “World Stage” series for women? I hope so, as long as it is as inventive as his first. When Wiley comes to the Brooklyn Museum in 2015 for an already announced solo show, the crowds and the critics might all be expecting a little more from someone who has not disappointed just yet.

Kara Walker Addresses Art and Controversy at the Newark Public Library

by Jessica Kramer

Conference Producer, The Conference Forum

Kara Walker is no stranger to controversy.

On Thursday, March 7, 2013, the African-American visual artist addressed a room of more than 100 people in New Jersey’s Newark Public Library to talk about her work and its most recent firestorm.

Walker, perhaps best known for her murals of stark silhouettes depicting often disturbing scenes of racial and sexual violence in black and white, creates work that elicits strong reactions. At the Newark Public Library however, one particular piece in its collection bothered employees to the point of censorship.

The graphite and pastel drawing in question, with the cumbersome but descriptive title “The moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos,” portrays an almost overwhelming amount of images clustered together. Included are hooded KKK figures alongside a burning cross, Obama at a podium giving his speech on race (“I think I put Obama in the picture last but I wanted it to spiral out from him,” Walker shared) and African Americans in various states of horror from the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, including one where a naked black woman, her back to the viewer, is pressed against a white man, performing fellatio on him.

This final image of sexual violence was the one to bother a couple of library employees. They found it offensive and so it was covered up with a cloth for several weeks until they decided against censoring the image any longer.

In the hour the MacArthur genius grant winner spoke with historian Nell Irvin Painter, Walker was by turns gently funny (even while addressing the perceived lack of humor in her work), incredibly insightful (expounding upon the themes she draws on and the responses to them) and dubiously naïve (in regard to the affordability of her work, some of which has sold for almost $400,000. A remark of “I don’t understand the market” was all she offered on that subject).

Walker started off by addressing race, which is a, and perhaps the, predominant subject in her work. She doesn’t shy away from the horrors of African-American history, which can lend itself to ire from black audiences, a not uncommon occurrence from other black artists as well.

Walker explained that that she wrestles with drawing any images of figures in terms of representation, let alone black ones.

“I really love to make sweeping historical gestures that are like little illustrations of novels,” she said.

She explores black identity in a transition point: between the rural south and urban north, “a psychic location where modern consciousness emerges.” Included in the library drawing are iconic situations: riots, dancing, and music, which exemplify states of transition and frenzy.

“It’s okay for me to like these things, and address these likes to other black women,” she said. “My references are riffs on types of stories or narratives, such as Gone with the Wind, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the Harlem Renaissance.”

Walker’s work stems out of her own personal struggles with identity.

“I never learned how to be adequately black,” she said. “I never learned how to be black at all.”

“Nobody knows how to be black,” Painter rejoined.

Walker said she is “bucking tradition by being an artist,” which is “often a struggle for many black artists.”

In California, where she grew up, and Atlanta, where she first went to college, black was a thing, she said. “Not just an identity or set of histories but a solid thing,” which is something that she tries to unpack in her work. Making silhouettes and rejecting proscribed ways of being and identities is a partial rejection of this as well as “a cloying acceptance.”

Walker is keenly aware of the possible implications of her work and asks critical questions of herself in regard to it, such as who is this work speaking to, who is buying it, and even what is this doing to the future of the race? Also, what is the audience’s responsibility to the art?

The audience and artist are isolated from each other, she said, and there is this “protracted war and fear.” Who gets access to the work and what kind of conversation happens when access is there?

Walker considers what it means to be a black woman here and now versus there and then and consequently addresses the themes of slavery and race. As a child, she would imagine living in different eras, but found the reality of them shaking her out of her reveries, realizing that it would be impossible to survive there.

Even though it may make her a self-proclaimed “daddy’s girl,” Walker named her father, a fellow artist, as one of her greatest inspirations.

“He made it okay [to be an artist],” she said. “I didn’t realize what a treat it was until I got to college. Art just became a way of being, of communicating.”

“Someone once told me, ‘You have to make the work that you want to see.'” Walker said.

She became interested in silhouettes, which as an art form were “sort of forgotten and small, female and domestic,” she described. They were done by “invalids and women,” along with “a few itinerant artists.”

Walker described her process, saying that, for her art, she carefully selects “black people, women, heroic figures in speeches,” elevating it to the level of political arena.

Walker, who called herself “an unreliable narrator in each of these works,” raises the question of what the outcome of using these archetypes, such as Obama, is. “Do these archetypes collapse history?” she asked. “They’re supposed to expand the conversation, but they often collapse it.”

In talking to people about her art, Walker recognizes the overpowering effect it can have.

“There’s a too-muchness about it,” she described, “a mute quality” that makes her and the viewer more complicit in the goings-on. It maintains anxiety and intensity and leaves it there.

The images come at you all once, unlike a book, Walker elaborated. The viewer doesn’t have time to get adjusted to what’s happening next, unlike the artist who lives with it for a while through the creation of the art in drafts and different versions. But, in the end, the viewer gets this “assault of stuff. It’s the quality that I respond to in art and in our identities.”

Some view her art as “severe and humorless,” Painter said, but a woman at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis was surprised by Walker’s gentle nature and compared her to Woody Allen. Painter agrees and sees a humor and playfulness to her work.

“Humor’s always been the problem of my work, hasn’t it?” Walker asked, laughing. “When working, I feel satisfied when I surprise myself. And when I surprise myself I wind up laughing.”

Walker spent the final 15 minutes taking questions (or simply the occasional glowing comment) from the audience, but it wasn’t until the final one that the topic of the Newark Public Library drawing even arose.

A woman referred to the “controversial art which has brought us all here,” but was interrupted by Painter before she could finish.

“You know you can just walk across the floor and view the work, right?” Painter asked.

Yes, the woman knew. Yet somehow, even with this query, the controversy in question was barely touched upon, perhaps to give it as little weight as possible and address other, more interesting ideas instead. Still, it’s a little ironic to avoid the subject almost entirely considering that Walker is an outspoken advocate of her bold work.

Indeed, in her art, Walker doesn’t shy away from both difficult and disturbing imagery as well as unbridled beauty. It is with this juxtaposition that she challenges viewers, making us uncomfortable but also strangely satisfied that such scenes are created in the first place. This “too-muchness” is just enough.

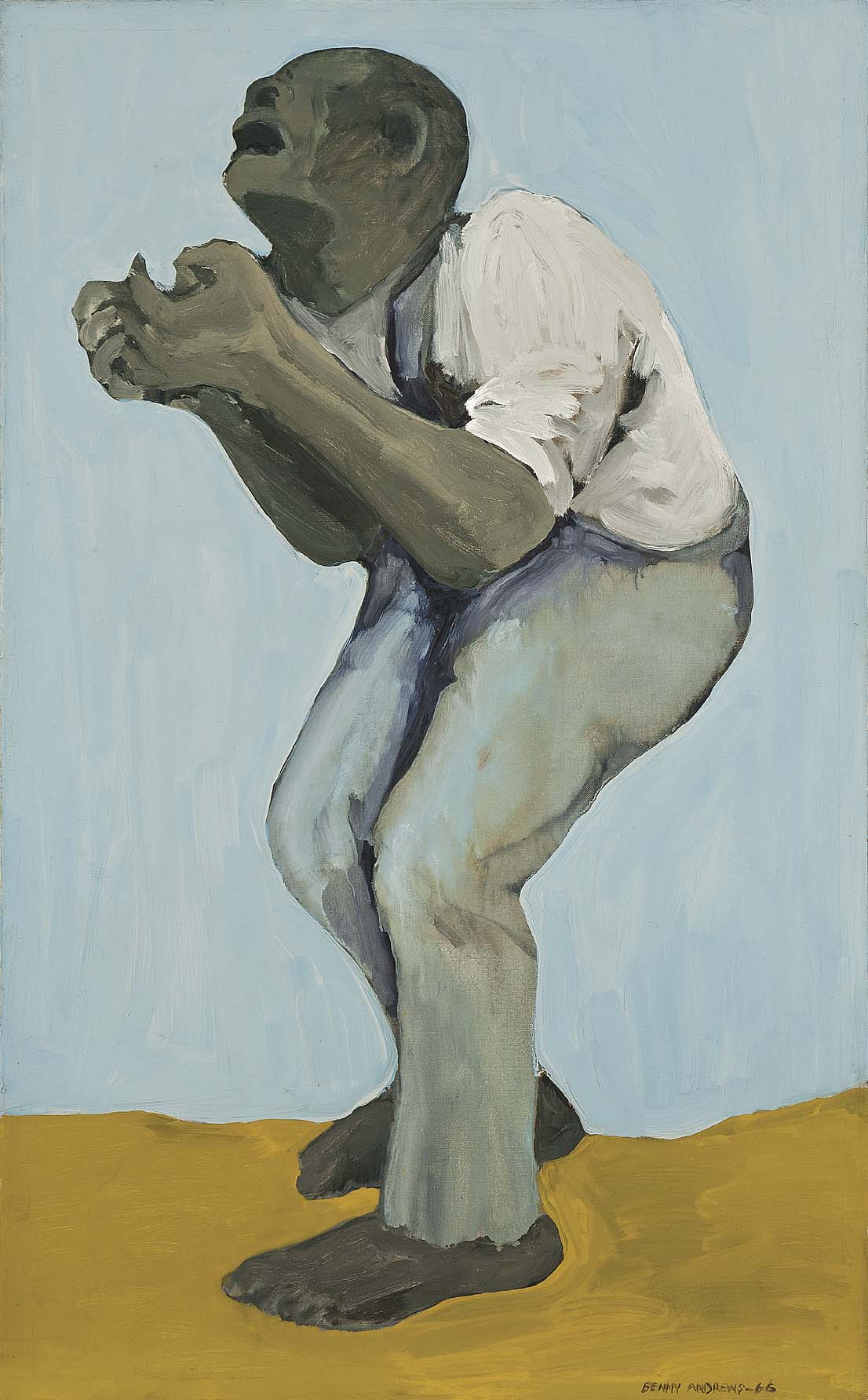

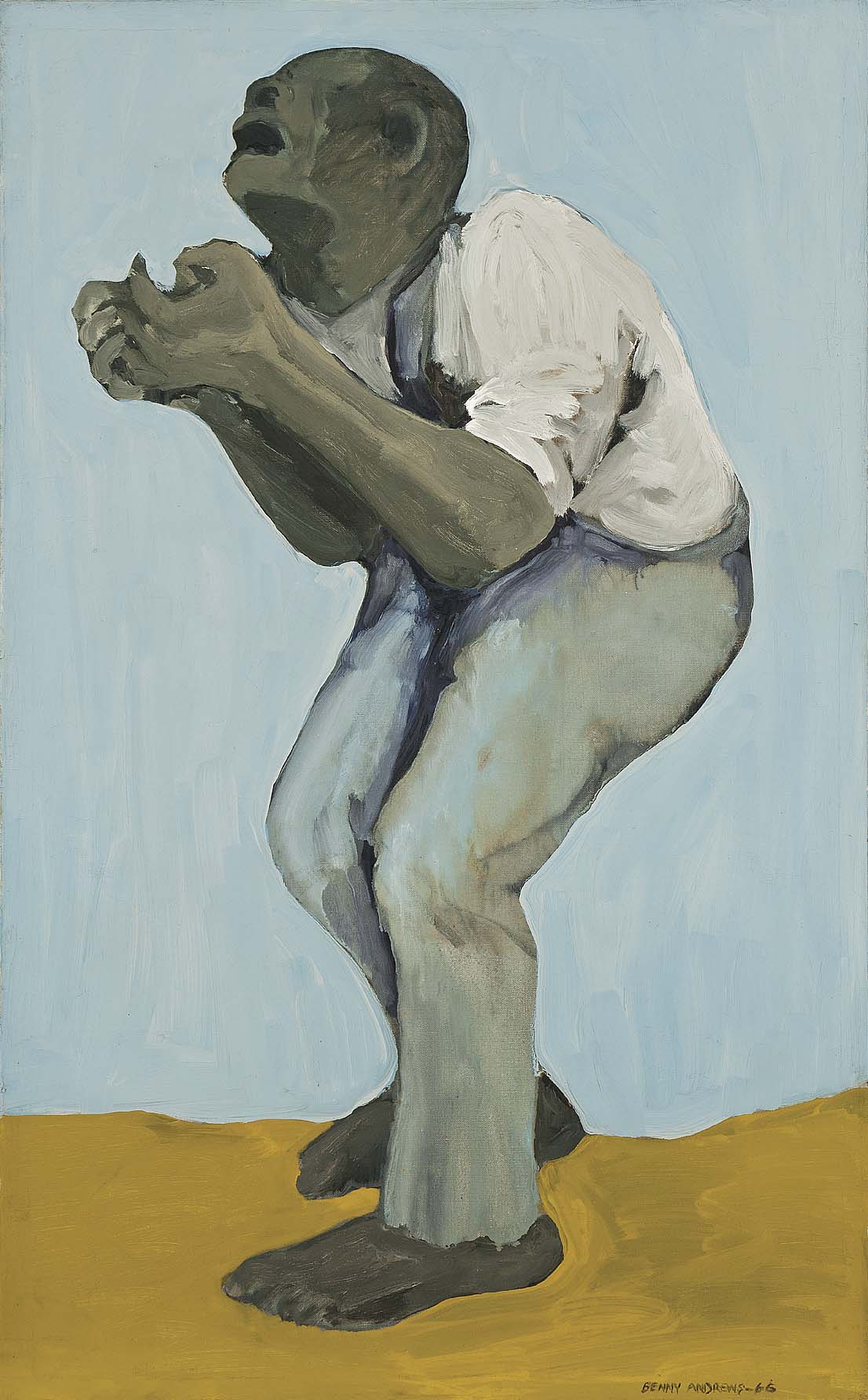

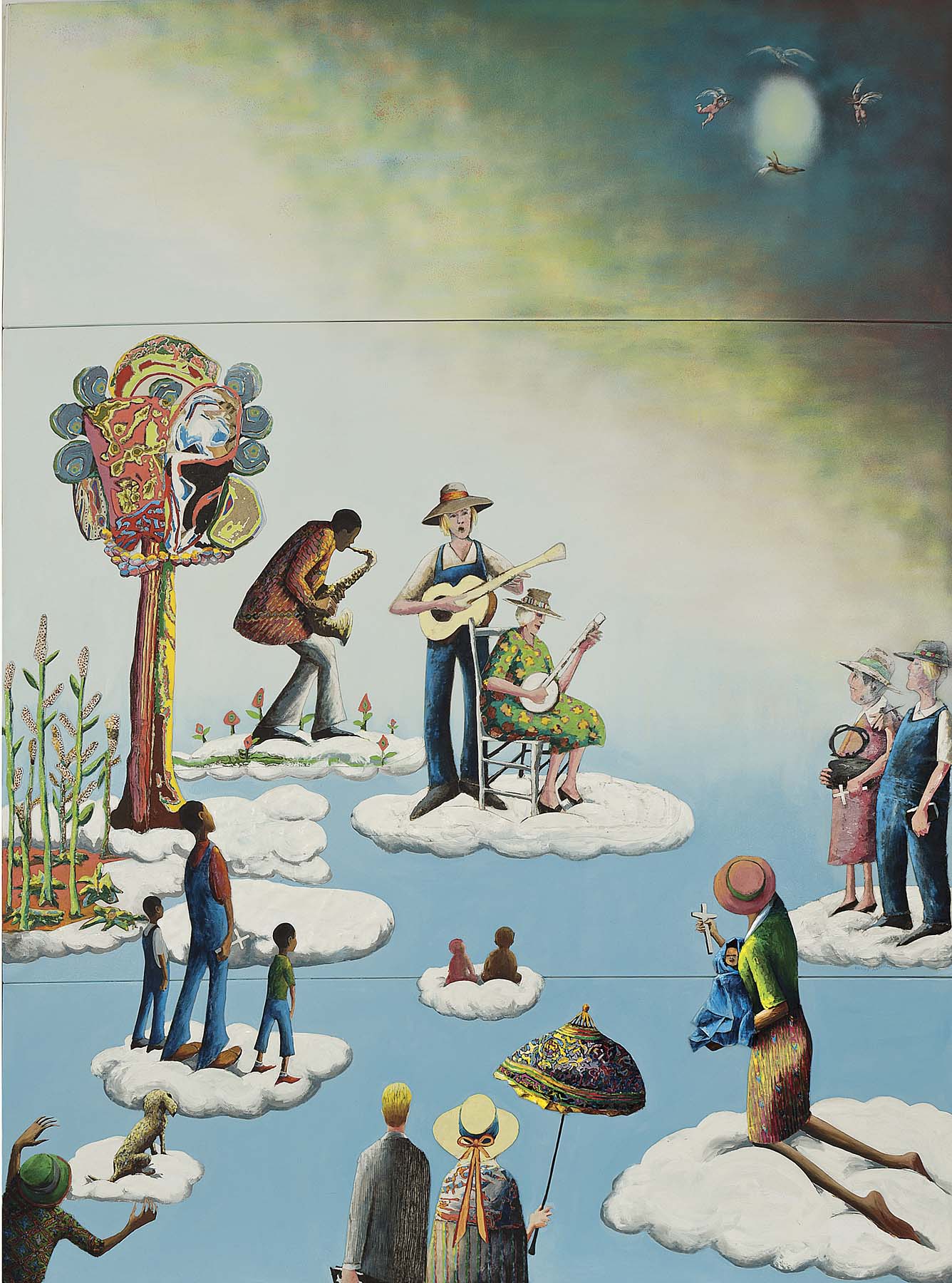

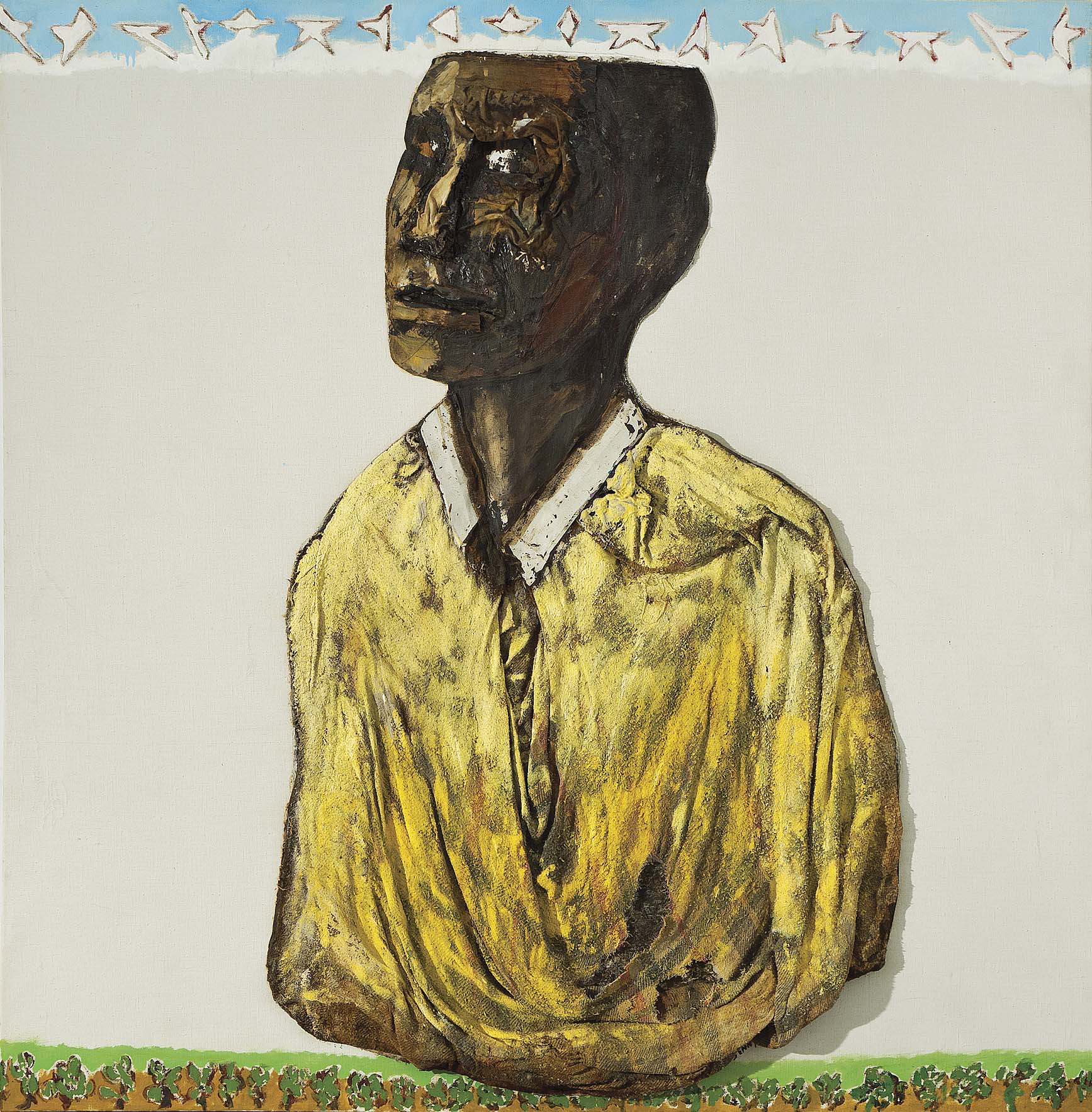

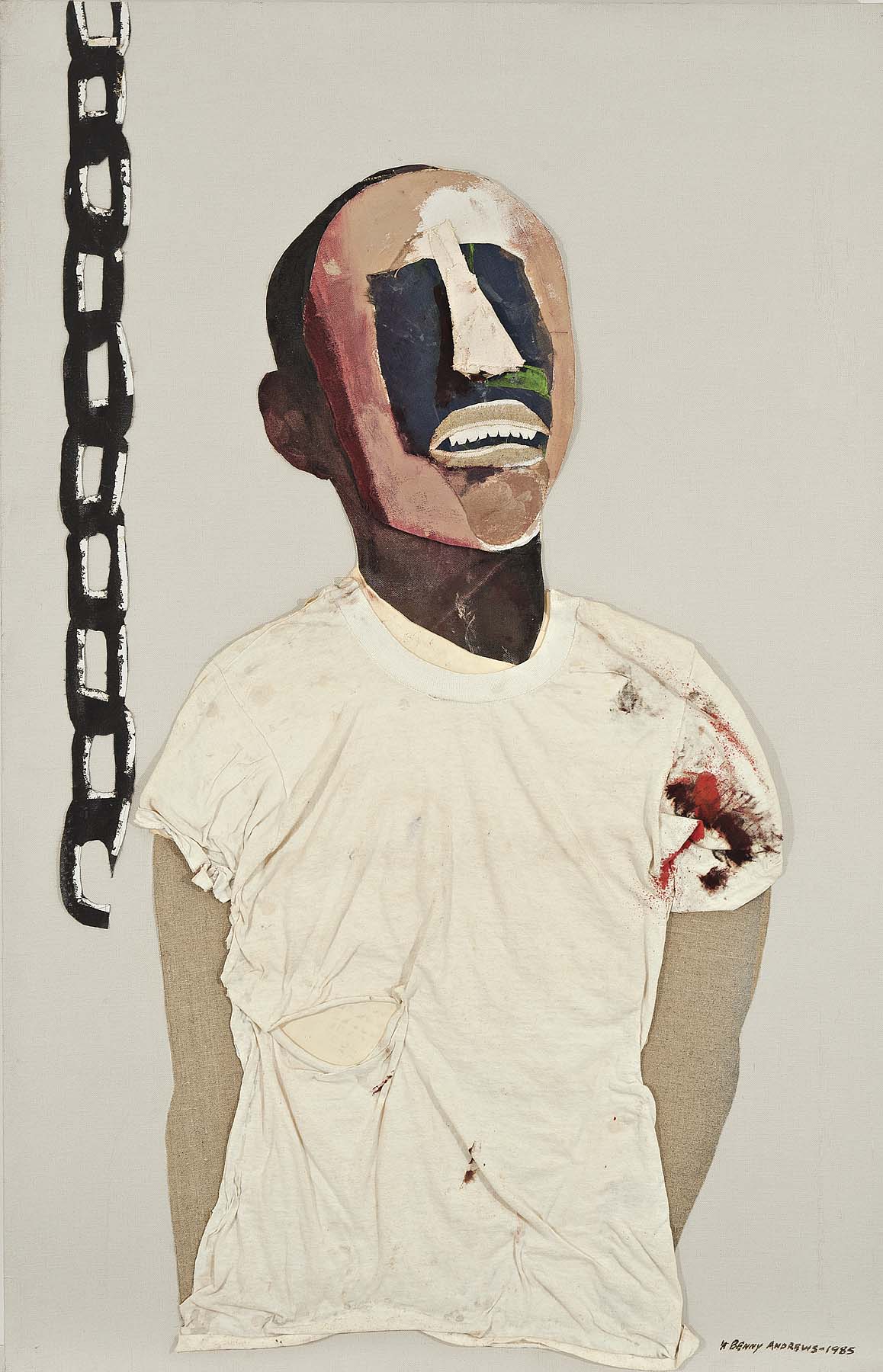

On Michael Rosenfeld’s Benny Andrews: There Must Be a Heaven

Bobby Elliott

Poet and writer living in New York City

For fans and collectors of 20th century African-American art, the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has emerged as the place to go. I visited in early February, shortly after “Storm Nemo” had come to town (leaving the streets slushy and the galleries almost empty) and some two months into their inaugural show at a sprawling, new space on 100 Eleventh Ave. INsite/INchelsea was the gallery’s introduction to Chelsea — they had been on 57th Street since 1989 — and it showcased the range and diversity of their artists. Not surprisingly, the names that stole the show were Andrews, Bearden, Delaney, Douglas, Lewis, Savage, Thomas and Thompson — all African-American pioneers of 20th century American art.

Benny Andrews: There Must Be a Heaven, up until May 18th, begins what I hope will be a long and illustrious run of exhibits teaching the neighborhood just how pioneering these artists were. Although Andrews has become known for his later images, which were typically easier and lighter, the strength of There Must Be a Heaven lies in showing how long it took for Andrews to get to a place of peace.

From the title work of the show, 1966’s “There Must Be a Heaven” :

To 2000’s’ “Baptist Heaven,” painted six years before Andrews’ passing:

There Must Be a Heaven spans Andrews’ entire career, showcasing some of his earliest paintings (1964’s “Many Sins,” 1965’s “Dinner Time”), some of his last (2005’s “Home Sick Blues” and “Mississippi River Bank”) and everything in between. Of the 40 years covered, Andrews was a desperate, anguished painter for the first 30 of them and, to my eye, the greater painter. There Must Be a Heaven doesn’t choose a side — it does a diplomatic, gallery job of paying homage to all phases of his career — but seeing the paintings he produced during that 30 year period, between the mid-60’s and mid-90’s, leaves little question as to where Andrews made his mark.

As the Rosenfeld show illustrates pointedly, Andrews was, for most of his life, a painter consumed and driven by issues of race, inequality, poverty and war. Although it took immense bravery to follow his conscience and speak to the issues in his art, you wouldn’t know it from Andrews’ first major attempts. There Must Be a Heaven begins with a long wall of these initial paintings, with the artist coming across powerfully and naturally. In tone, they are not docile (1970’s “Symbols Study #2” is especially chilling), but they are not simple political paintings either. “A Soul,” showcasing Andrews’ expressive realism, could have said more about the cotton fields at the base of the painting, but instead it focuses on the withstanding grace of its hero. The sense that Andrews was already then the painter he wanted to become — a “people’s painter” –is inescapable.

Outside of a brief period in the early ’70s when his images relocated to an alternative, dream-like setting, There Must Be a Heaven tells us that Andrews stayed the course, sticking to mostly figurative scenes while developing a growing facility for collage. His concerns widened, becoming more global and historical over time, but he never ventured far from the figures of “There Must Be a Heaven” and “A Soul.” Aching, many of them, they share the same unflinching quality of Faith Ringgold’s “American People Series” (currently at ACA Galleries) while owing equal debt to Jacob Lawrence and his deservedly beloved history paintings. As the show’s title suggests, Andrews’ work was not without its hope — hope for peace and unity one day, or at least the two in heaven — but it was relentless in its commitment to truth and honesty. Whether confronting his southern past or Apartheid in South Africa, he continually found new reason to voice his concern and compassion for the world and for those it held captive.

All of this gave his paintings up until the 1990’s a searing, uncompromising way. No doubt because of this and Andrews’ own marginalized place as an African-American artist, they were rarely shown. Michael Rosenfeld, which represents the Andrews estate, has begun to change that with There Must Be a Heaven, filling its first room and half of its second with the paintings of Andrews’ emergent and mature years, paintings I doubt I will ever tire of. They are powerful, often difficult pictures to face, Andrews at his prime — I only wish they were part of a traveling exhibition, headed to Congress next.

The emergence of Andrews’ softer side in the last decade of his career is a problem not easily reconciled in scholarship or in There Must Be a Heaven. Late in life, artists tend to loosen, producing what they want to produce and caring less of the implications. It shows in the last quarter of the Rosenfeld show. Andrews’ change of course toward a more agreeable art — both in figuration and in temperament — happened somewhat gradually. 1996’s “Confinement One,” an image produced four years before “Baptist Heaven,” is a noticeably more charming portrait than “Study for Portrait of Oppression,” for instance, but then you realize that the man pictured is still a prisoner, his feet shackled and his pants striped. As the later works shift, they look toward music, and sometimes religion, to believe in a greater future and peace, eventually getting there with little hesitation. After a career of painting incinerate, indicting pictures, the transformation can feel a little too easy and my fear is that there are already too many people out there who have chosen the comforting arms of these late images, the preceding thirty years finally proving too hard to look at.

Of course, the images hardest to look at are the images closest to home. There Must Be a Heaven brings us home, spending most of its time in the good and difficult room of our consciences. If this show is any indication, we are in for many more, the kind the doctor and the nation ordered. Who’s next? Alma Thomas would be my pick, Mr. Rosenfeld.

NEW HAVEN: Ficre Ghebreyesus

Polychromasia

…When I paint I am accompanied by dissonances, syncopations, and the ultimate will for life and moral order of goodness. A trip to the market guaranteed a dazzling range of traditional crafts repeated from one generation to the next without ongoing critical intervention and independent of religious function. These crafts included a dazzling range of works such as reed baskets and hand-spun, hand-woven embroidered cotton garments in exquisitely-resolved colors. The caves near my mother’s village are full of prehistoric rock drawings and paintings. My eyes took in all of this; my painting allowed me finally to process the seemingly dissonant visual information.

Nigeria’s Biggest City Holds A Carnival (PHOTOS)

LAGOS, Nigeria — In Nigeria’s biggest city, a Monday morning typically sees bumper-to-bumper traffic as people struggle through heat and exhaust fumes to get to work. This Monday, however, the roads were not filled with cars, but with people celebrating the Lagos Carnival.

Dancers in colorful costumes resembling those of Brazil’s Carnival shimmied and shook their way through the streets.

This year, Lagos’ state government said the festival would commemorate the region’s historical ties with Brazil. Portuguese explorers once came to the region and Brazilian-style homes can still be seen in the city’s older neighborhoods.

The curious lined up to watch and take mobile phone pictures, some ogling the women dressed in bikini-styled outfits. Tuesday, though, the streets will again jam with traffic.

Here are some Associated Press photographs of this year’s festivities in Lagos.

This year, Lagos’ state government said the festival would commemorate the region’s historical ties with Brazil. Portuguese explorers once came to the region and Brazilian-style homes can still be seen in the city’s older neighborhoods.

The curious lined up to watch and take mobile phone pictures, some ogling the women dressed in bikini-styled outfits. Tuesday, though, the streets will again jam with traffic.

Leslie Cheung Exhibit Pays Tribute To Memory Of Hong Kong Singer-Actor On 10th Anniversary Of Death

Origami cranes, folded by fans are displayed at an exhibition for paying tribute to Leslie Cheung at a shopping mall in Hong Kong Saturday, March 30, 2013. The exhibition is held to mark the 10th anniversary of the death of Hong Kong screen and singing legend Leslie Cheung. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

HONG KONG — Almost 2 million origami made by fans in memory of singer-actor Leslie Cheung are being displayed in Hong Kong at an exhibition marking the 10th anniversary of his death.

The “Miss You Much Leslie Exhibition” at the Times Square shopping mall is one of many memorial events in his hometown.

Many fans discovered Cheung after his passing. “I really miss him, and I regret that I did not get to know him until 2009,” said Kang Lizhen, a mainland Chinese who was born in 1990.

Those who discovered him after his death feel like they lost a friend, said one such fan, Marie A. Jost. “There will be no new works, no new events, no news of Leslie … It really does feel that we’ve lost a dear, dear friend,” said Jost.

Cheung killed himself by jumping off the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in central Hong Kong on April 1, 2003. His death came at a dark time for his hometown as Hong Kong was hit with the SARS epidemic (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome). Hundreds died in the illness outbreak that also crippled the Hong Kong economy and cast a gloomy pall on the normally vibrant and energetic city.

Cheung, who was 46 when he died, made several hit albums and starred in classic films including 1987’s “A Chinese Ghost Story,” director John Woo’s “A Better Tomorrow” and Chinese director Chen Kaige’s “Farewell My Concubine.”

A memorial concert was held Sunday, and Cheung’s fans mark his death anniversary each year by visiting the hotel where he committed suicide. One wall of the hotel is covered in flowers, candles and posters of the singer and actor.

Fans sent in volumes of crafted paper this year to try to set a Guinness record for most origami made for a cause. Organizers said 1,900,119 were collected.

The memorial origami are displayed in a transparent archway above a large statue of Cheung at the “Miss You Much Leslie Exhibition” entrance, and one large, red origami sits in the statue’s open palm. The exhibition showcases costumes from his concerts, and a mini-theater plays films and interview clips.

Investing in Art and Photography

A free guide to investing in Art and Photography

Investing in Art and Photography

“… the search for alternatives to the classic forms of investment will ensure that art as an asset class will enjoy an unimagined upswing.”

Wolfgang Wilke, vice-president, Dresdner Bank’s economics department

The art and photography sector is awash with stories of savvy buyers, who spotted the potential of an artist at an early stage, and are now cashing in on the deal.

And if you can find the next Warhol, good on you.

Here at Paul Fraser Collectibles we advise those investing in art to focus on the more secure end of the market – the works and autographs by the blue chips of the field. These are the areas that have traditionally shown the greatest appreciation and the least volatility, whether you’re talking about old masters, impressionists, or the contemporary stars of today.

Reasons to invest

A growing market: 1m people worldwide now consider themselves serious art collectors, compared with just 10,000 in 1980 – a testament to the increasingly global nature of the art world, with China, India, Russia and the Middle East now particularly prominent. Christie’s art sales saw a rise of 13% in the first six months of 2012 compared with the same period in 2011.

Chinese influx: The world’s rapidly expanding, second largest economy is now the world’s largest market for art and antiques. China’s share of global art sales rose to 30% in 2011, up from 23% in 2010, overtaking the US into first place. As the increasingly prosperous country continues to create more and more millionaires, expect to see prices soar as Chinese buyers repatriate their country’s artwork, from auctions all over the world.

Contemporary art is a boom sector: 87% of the world’s 200 leading art buyers own contemporary pieces, stated the 2012 Artnews 200 report.

Limited quantity: The majority of the leading investment-grade artists are no longer with us. This finite supply coupled with a growing demand ensures that values are rocketing – now is the time to capitalise.

Soaring values:

o The Mei Moses index revealed that values across all art sectors grew by 10.2% in 2010, and 7.7% pa between 2007 and 2011.

o Chinese art grew in value by 20.6% in 2011, according to the index.

o Old master and 19th century artworks were up 5.4% in the first half of 2012.

Historical performance

o Art

Edvard Munch’s The Scream sold for $119.9m at Sotheby’s in May 2012, raising the art auction world record by 12.6%, previously owned by Picasso’s Nude Green Leaves, and Bust, which sold for $106.4m in 2010.

The Qatari royal family bought Cezanne’s Card Players for $250m in 2011 in a private sale, a world record for a work of art.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Warrior sold for £5.6m ($8.7m) in June 2012, 14.87% pa up on the £2.8m ($4.4m) figure it achieved at Sotheby’s London in 2007.

Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow smashed the world contemporary art auction record when it sold for $86.9m in May 2012, 19.3% up on Francis Bacon’s Triptych which achieved $86.3m in 2008.

Joan Miró’s Peinture Etoile Bleue realised $36.9m in June 2012, breaking the artist’s record by 22.9%.

Andy Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills sold for $43.8m in November 2009. The seller had originally purchased the piece for $385,000 in 1986 – a 23% pa return.

Herge’s original cover artwork for Tintin in America sold for €1.3m ($1.6m) in Paris in June 2012, setting a new world record for cartoon art. The price was 14.4% up on the old record, set by the same work in 2008.

o Photography

Rhein II by Andreas Gursky made $4.3m in November 2011, setting a new mark for the world’s most valuable photograph. It beat the previous record of $3.89m by 11.3%, set by Cindy Sherman’s Unknown #96 in May 2011.

o Artists’ autographs

Salvador Dali signed photographs rose in value by 11.88% pa between 2000 and 2012, from £325 ($515) to £1,250 ($1,985), according to the PFC40 Autograph Index.

Picasso signed photographs rose in value from £1,400 ($2,225) to £3,950 ($6,270) between 2000 and 2012, at a rate of 9.03% pa.

Contact us for further information on investing in art and photography on +44 (0) 117 933 9500 or info@paulfrasercollectibles.com

View our art and photography stock for sale here.