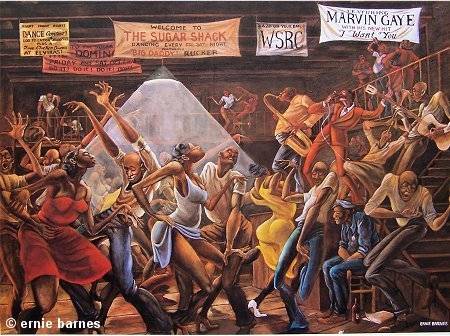

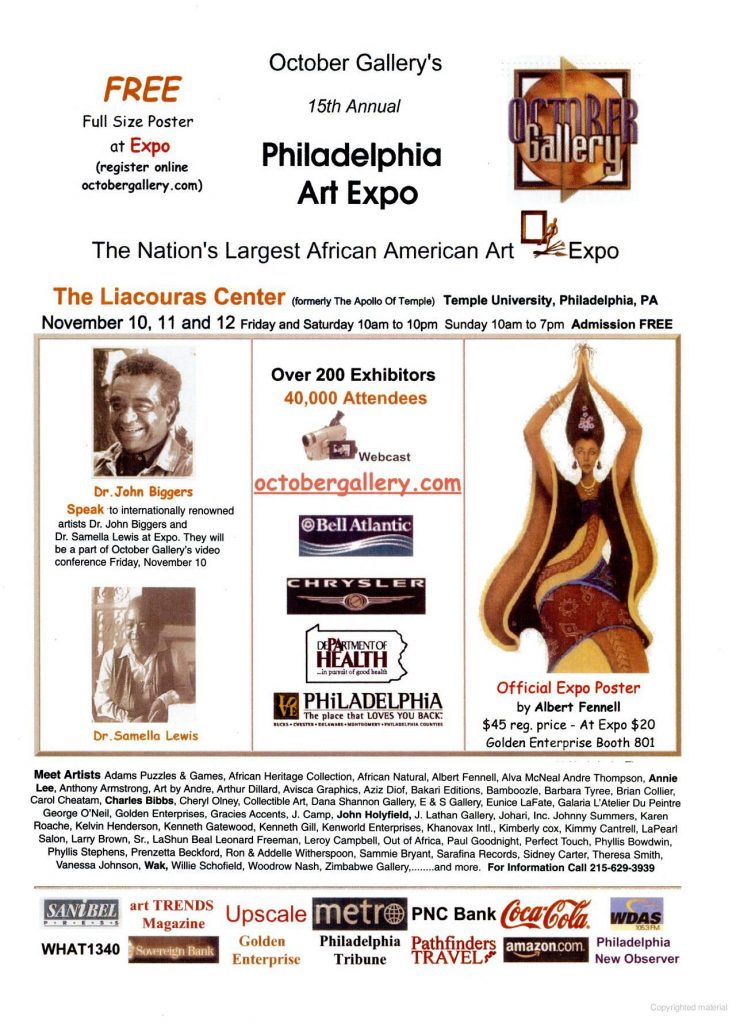

BET TV Angela Stribling Host Video of Expo 15

This was a video conference at the Philadelphia International Art Expo. October Gallery.

In 2000 October Gallery produced a video conference with artists Dr. John Biggers and Dr. Samella Lewis. This video conference was part of the annual Philadelphia International Art Expo

Dr. Samella Lewis & Artist Jimi Claybrooks – October Gallery

Part of the Philadelphia International Art Expo.

They met in college. He was class president. She was active in student council and her sorority. The attraction was mutual.

“Evelyn had skills,” recalled Mercer Redcross of his future wife and business partner during their days at Fisk University in Nashville in the late 1960s. “She would come to the dorm, in the lobby, and type up invitations for campus events.”

Mercer was an economics major from 57th and Girard in West Philadelphia. Evelyn was a psychology major from Orangeburg, S.C.

The big-city boy and the small-town girl met one spring day, married nine months later and moved to Philadelphia.

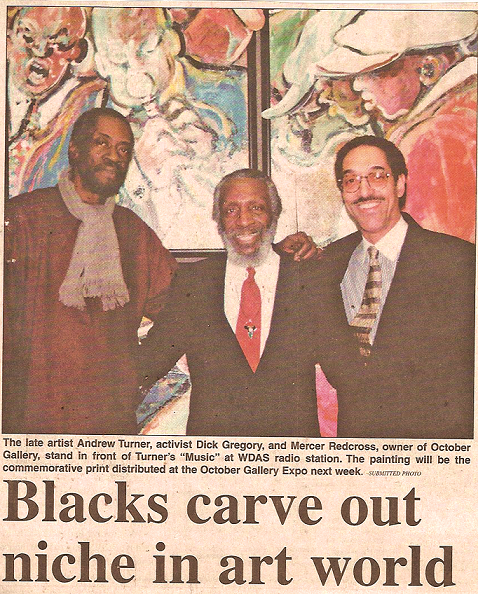

Years later, after becoming avid art collectors, Mercer and Evelyn Redcross opened October Gallery in West Philadelphia and created one of the largest black art expos in the country.

The 15th annual Philadelphia Art Expo opens today at the Liacouras Center, with more than 200 artists and vendors playing host to 40,000 people.

“They have done more for the local artists than any other gallery in Philadelphia,” said Cal Massey, an artist from Moorestown, N.J., whose signature piece is “Angel Heart,” a black angel with upswept hair. “They’re the ones that bring the people to us. Otherwise, they wouldn’t know about us.”

The Redcrosses didn’t plan to go into the art business. After their move to Philadelphia, Mercer got his bachelor’s degree at Cheyney University and MBA at Eastern College. Evelyn finished at Temple and also earned a master’s degree in journalism there.

He became a bank officer, and she became a welfare caseworker.

“We were art collectors first,” favoring mostly European artists, such as Salvador Dali and Giovanni Battista Moroni, Evelyn said. “But we were excited about the work of African-American artists. The only setback was we had to go everywhere to find it.”

So they decided to open a gallery, figuring it was the best way to get the work of black artists under one roof. They opened October Gallery at 38th Street and Lancaster Avenue in 1985.

The timing seemed right. Prints and paintings by black artists were appearing each week on the walls of the Huxtable household in the popular sitcom “The Cosby Show.”

“We weren’t thinking about Bill Cosby when we started,” Evelyn said. “We thought we couldn’t be the only people who saw value in this product.”

They weren’t. Still, many blacks weren’t used to seeing images of themselves in traditional art, so they were slow to commit to purchasing anything. And the Redcrosses learned that just enjoying art isn’t enough if you have a gallery.

“You have to approach it as a business and art happens to be the byproduct,” Mercer said.

In business terms, you might say that Mercer, 52, is the marketing guru, while Evelyn, 51, who has worked for the Barnes Foundation and taken art courses, is the product manager.

The Redcrosses, who have three adult children, make a good team, customers say.

“Their love of art is contagious,” said Leslie Fletcher, 51, chief of staff for state Sen. Vincent Hughes.

Regina Henry, executive editor of Philadelphia Black Network magazine, counted the October Gallery art in her Center City office.

“I’m looking at three Beardens, a Byrd. . .the Austino, eight, the Turner, nine. . .” Finally, she rounded off the count at 20 pieces. “We have a gallery within our offices.” October Gallery was in West Philadelphia for nine years before moving to Church Street in Old City and finally to 68 N. 2nd St., along a row of art galleries.

From the beginning, road shows were important to increasing the gallery’s name recognition nationally. Annual 35-city tours became the norm. Marketing was crucial.

“We needed to stimulate art, not just in Philadelphia,” Evelyn said. “We had to set sparks off all over.”

With its slogan – “Connecting people to art” – the gallery works with newcomers as well as more high-end buyers. It also provides a place for up-and-coming artists to display their works.

The old Dunfey Hotel on City Avenue was the site of the first expo, which was attended by 900 people. As its popularity grew, the expo had to move to accommodate the crowds – The University Sheraton, the Wyndham Franklin Plaza. Adams Mark hotel, the Pennsylvania Convention Center, the Philadelphia Marriott. Since 1998, it’s been housed at Temple’s Liacouras Center.

The expo’s success is due in part to saturation advertising. Mercer has run ads in magazines such as Essence, Black Enterprise, Art Trend, Ebony and Upscale, as well as local and national newspapers.

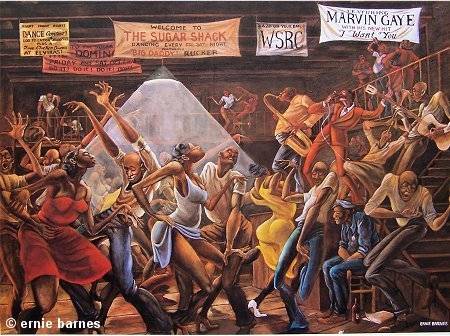

It includes workshops and draws poets and prominent African-American artists such has Charles Bibbs and Annie Lee.

It’s an educational experience as well. Groups of schoolchildren will be brought in tomorrow to learn about art from the artists. During the showcase, customers can talk to the artists.

Coincidentally, Terrence Gore, a young African-American gallery owner, will open an exhibit today featuring the work of Afro-Brazilian painter Menelaw Sete, “the Picasso of Brazil.”

Gore deals with expensive originals in his South Street gallery, Galerie T’ Elgee.

Of the expo, Gore said, “I don’t feel in any way that will impact me. I have a clientele who are collectors specifically of fine art. They’re not in prints in any way.”

Gore said the expo is good because it has “evoked an awareness of people of color to their culture.”

But he said he thought it should be “a little more extensive.”

The Redcrosses see their mission as educating. They offer prints for $20 with other pieces ranging up to several thousand dollars. The average is $400 to $500.

“The African-American culture speaks to how people live,” Evelyn said. They try to create an atmosphere “where people come to experience the culture to take from it, to dip in it and take what they need.

“We’ve introduced a lot of people to art. And many are now aficionados.”

*

OCTOBER GALLERY’S 15th ANNUAL PHILADELPHIA ART EXPO, Licacouras Center, 1776 N. Broad St., 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., today and Saturday; 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Sunday. Free. 215-629-3939.

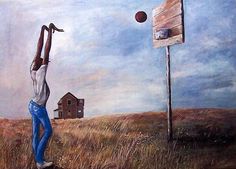

Artist: Lester Kern

BY Jerry Harris

This article was first published in 1999 in Philadelphia City Paper

When someone suggested that I go and see the black art show at the Apollo of Temple, I didn’t know what to expect. I was new in Philly, and I thought that this might be the local version of the famed Apollo theatre in Harlem where our best and worst got a chance to perform. I called my sister’s boyfriend for directions. “Is it far from me?” “No, it’s located in the ghetto surrounding Temple University, but the school doesn’t broadcast that.” Ah! Race is such a factor in this city–really there is no escape.

It’s billed as the “14th Annual October Gallery Philadelphia Art Expo in Celebration of an American Phenomenon—Whew! The title didn’t suggest an awareness of minimal art, and it put a dent in my allotted 650 words. Anyway, what’s so phenomenal about African-American art? We’ve had African-American artists as far back as Pittsburgh, Pa. born Henry O. Tanner—hatched in 1859. Tanner’s work even begs the question: What is black art? His work is indistinguishable from that of his white contemporaries–pre-modern portraitists and landscape artists.

Cooking up labels is as American as Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans. We have feminist art, hispanic art, and even elephant dung art, which is being shown at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York City, and has made Mayor Rudy rude. It is all Chinese to me. Certainly each artist brings his or her temperament to a work of art, but at the end of the game, art is the winner.

A week before the show, I listened to Mercer Redcross, owner of the October Gallery, and promoter of the exhibition. He was guest on a local black radio station. “The mainstream media has never given much space to the event,” he said. I couldn’t confirm that, but I certainly was going to go and support my brothers and sisters. Two of the participants were on the show with Mr. Redcross. One painted children’s pictures, and the other artist, a former technocrat, said that he liked to paint boxers who never fought each other—Muhammad Ali bumping off Joe Louis. Well, LeRoy Neiman, the society painter, has made millions painting boxers and other celebs, so why not this guy?

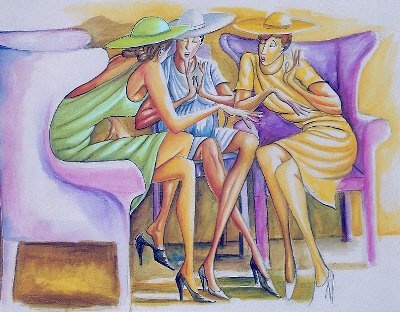

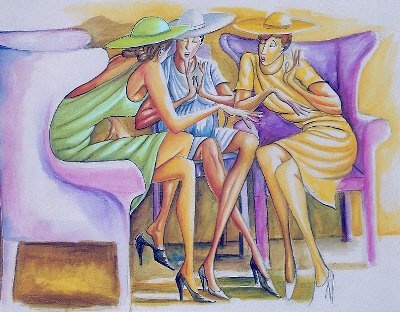

Friday art night arrived and I emerged from the Cecil B. Moore station, and got my first look at Temple University—a row of rather uninspired buildings. I entered the Apollo of Temple (weird name) and was greeted by two beauties. Philly must have the greatest concentration of beautiful black women on the East Coast. There was a fairly good crowd of African Americans walking about, looking and talking to the artists who had their wares on display. The work was a 50-50 split between art and crafts. All of it, with the exception of a few, emphasized African-America themes: family, roots, children and society—nothing wrong with that, but most of it was commercial flimflam from the velvet school of art.

Now (using the words of our low-esteemed Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas) “high-tech lynch” me if you will, but there was a lot of bad art at the Apollo, and if this show was likened to the famed Apollo shows in Harlem, a lot of tomatoes would have been tossed at the participants.

Where were our leading African-American artists? I mean critically acclaimed artists, such as Martin Puryear, Richard Hunt, Sam Gilliam, Betye Saar, and Lorna Simpson? Mr. Redcross would have served the white and black community much better by having a crafts show and a separate professional exhibition at his October Gallery. Well, arty-tarty, I left and went over to Baltimore Avenue, ordered a pizza and a well-deserved beer. The waitress asked a long-haired customer what he was painting these days. “Oh, just a still life with a coca-cola bottle,” a perfect description of my night at the Apollo.

Site allows consumers to buy black art online

Something about “Trouble Ahead” bugged Terrie Rouse.

After walking down the ramp to the third-floor gallery of the African American Museum in Philadelphia, Rouse made a quick left, strolled over to the painting by Columbus Knox and carefully straightened it.

“I want the museum to be known for being the best of the best,” Rouse would say a few moments later.

It’s coincidental, but more than appropriate, that Black History Month marks Rouse’s six-month anniversary as the museum’s executive director.

The museum is taking steps to become, as Rouse says, a professional showcase of African-American art and culture – at a time when more collectors of African-American art are themselves maturing and looking for the best of the best.

When blacks began collecting black art in the late 1970s – some spurred by paintings displayed on the walls of the Huxtable household in “The Cosby Show” – they favored low-end pieces, said Mercer Redcross, co-owner of October Gallery on N. 2nd Street. Now those same buyers “want to know where the top is,” he said.

A good example of that desire was evident last weekend at the National Black Fine Arts Show in New York. Featuring works from 41 galleries from around the world, the event drew 8,000 to 10,000 people, organizers said. People stood shoulder to shoulder viewing and purchasing original works by such African-American artists as Romare Bearden and Henry Ossawa Tanner.

“It was great,” Rouse said. “You saw African-Americans doing the range of art,” from realism to abstract. And Rouse was pleased that her winter exhibition, “Rejuvenating a Collection: Ford Foundation Artists and Acquisitions,” which opened in January, reflected the same range.

The museum is also one of nine across the country participating in the “Perspectives in African American Art” program sponsored by Seagram’s gin. The program provides grants to museums for artists-in-residence programs and commissions to “emerging artists.”

Mixed-media artist Martina Johnson-Allen of Philadelphia has been commissioned to do a piece for the Philadelphia museum.

“The Seagram’s program has been growing,” Rouse said. “To have artists selected by various communities and have them put forth is a wonderful thing.”

Sande Webster, whose gallery at 20th and Locust streets specializes in African-American art, has been in the business for 30 years. She realized early on that there were African-American artists “of comparable quality and ability of Caucasian artists, who were not receiving anywhere near the kind of recognition they should’ve been.” “There’s a real interest in people having access to material that represents themselves,” Rouse said.

To spur that interest, Rouse, 45, has given her 23-year-old institution a new look.

The museum building’s gray concrete interior has been repainted white. Some gallery walls have been painted brown, to set off photographs by jazz bassist Milt Hinton; other walls got the “ice storm blue” treatment to complement paintings and sculpture.

“Exhibits should look a certain way,” Rouse said. “Museums are all about the creation of feelings and illusions.”

The lighting in the lobby is brighter. “It was always dark,” Rouse said, giving the museum “a sense of foreboding.”

Then there’s the collection.

Webster has seen it evolve over the years. The museum “didn’t own anything” when it opened in 1976, Webster said. “As the collection has grown, it has developed a point of view. A lot of artists in the collection are well-established now. It shows the museum had some foresight in its purchases.”

In 1990, the museum used a Ford Foundation grant to purchase works by Moe Brooker, Paul Keene, Syd Carpenter, Howardena Pindell, Charles Searles, Richard Mayhew and John E. Dowell Jr.

With a 1993 Ford grant, the museum bought works from Pat Ward Williams, James Brantley, Charles Burwell, Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Martina Johnson-Allen and Louis Sloan.

The museum is tracking attendance, has inserted programs geared to the community, published a calendar and changed its name. It was formerly the Afro-American Historical & Cultural Museum.

All of this comes as Rouse dreams of getting the museum accreditation and making it “feel like Disneyland, but only for a lot less money.”

Rouse, a museum professional for 19 years, said she wants to bring the African American Museum in Philadelphia into the “museum world.”

“There are standards in our business,” she said. “There are things we have to adhere to,” such as making sure objects are well-lit, that information about a display is easily available, that historical documents are properly displayed.

But “institutions go through cycles,” she said. “We tend to be too hard on ourselves. This institution is going through development, as it should be.”

Nona Martin, the museum’s director of education, notes the museum is more than just a place to hang pictures.

“It’s not about displaying African-American art,” Martin said. “It’s about interpreting and displaying African-American culture.”

“Visitors need to walk away feeling that this was a wonderful experience,” Rouse said. “That’s what will bring them back.”

Philadelphia photographer Pierre Baston attended last October’s Million Man March for one reason but quickly discovered he was really there for another.

An accomplished movie and still photographer, Baston is a 1975 Yale grad who also dabbled in acting while earning his BA degree. In addition to a flair for the dramatic, he also brings skills as a lighting director to his vision of the world.

The Million Man March, Gaston says, represented “an opportunity to practice photojournalistic technique.”

But, he says, his interest was quickly drawn from the political aspects of the gathering to the cultural and aesthetic ones. He noticed, for example, that “many African-American men and women there expressed themselves powerfully in the artwork on their clothing, or the style of their hair.”

Camera in hand, Gaston shot and shot and shot . . . and the result is “a mini-series on the eloquence of backs, the subjects set against the gleaming symbol that is Capitol Hill.”

The collection, focusing on individuals rather than on large crowds, shows the character of the event from a single marcher’s point of view. It opens FRIDAY with a free reception from 5 to 9 p.m. at October Gallery, 217 Church St. The show also can be seen there throughout the month during the gallery’s regular hours, Mondays-Fridays from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Saturdays from noon to 6 p.m. Info: 215-629-3939.

FEET FEAT. You’ll get your kicks when they do their kicking – “they” being the members of the Veryovka Ukrainian National Dance Company, which is touring the United States for the first time. The troupe, which draws on folk music, art and dance from across the Ukraine, comes to Philadelphia FRIDAY to perform historical ballads, Cossack and chumak songs and dances, scenic compositions and works of holiday celebrations. The troupe was founded in 1943 by Hrihory Veryovka in Kharkov, shortly after the city was liberated from the Nazis. It continues today under director Anatoly Avdiesky and has performed regularly throughout Europe, Canada and Mexico – but this is its first trip to the States. The “All Star-Forum” program is at 8 p.m. at the Academy of Music, Broad and Locust streets. Tickets: $14-$40. Info: 215-735-7506.

MANN MADE. “I’ve spent a lot of time in L.A. the past year, playing little shows, writing songs, but basically not doing much,” confesses Aimee Mann, the throaty pop-rock chanteuse best known for her hits with Til Tuesday (remember “Voices Carry”?) and last year’s “That’s Just What You Are” from the “Melrose Place” soundtrack. Mann was supposed to parlay the latter hit with her own album, “I’m with Stupid,” a most tuneful jangle-pop collection with a surprisingly hard and sometimes bitter core. But the disc’s release was delayed until just last week because Mann’s record label Imago abruptly folded, and it took eons for a new distribution deal to be hammered out with Geffen. “I was always thinking I can’t go anywhere, ’cause any minute now it’ll come out,” sighs the singer/songwriter, who headlines TLA with a band SATURDAY night. “I feel like I’ve finally been let out of a cage.” Semi-Sonic opens Mann’s show at TLA, 334 South St. 8 p.m. Tickets are $13.50. Info: 215-922-2599.

January 4–11, 1996

critic pick|art

If you’re planning to make the rounds during the first First Friday of 1996, here are a few shows to watch out for.

Pierre Baston’s photographs at October Gallery (217 Church St.) and Other Bloods at the Painted Bride (230 Vine St.) both address the lives of African-American men today — Baston through photos of the Million Man March, and OtherBloods through the work of six artists from NYC, Washington and New Jersey who came of age in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

The winners of the third annual Phila. International Contemporary Art Competition of Old City, or PICACOC III, will show their work at six participating galleries in the 2nd/ 3rd/ Arch area: Feduluv, Medici, Gallery Alexi, Pentimenti, Rodger LaPelleand Silicon, and at Cafe Einstein (208-10 Race). The estimable art critic and curator Judith Stein was this year’s juror.

Psychedelia, New Orleans, food packaging and a “Stuffed Elephant Lamp” figure in the show of new members’ works at Vox Populi (17-19 N. 3rd), while the member artists of another co-op, Zone One (Second Street Art Building, 139 N. 2nd), havegiven their January show the seasonally correct title of Resolutions. Also in the Second Street complex: Skirting the Issue: The Dress as Sculpture at Nexus, Standard Deviation at High Wire, and solo shows at the Clay Studio byMatthew Courtney and Yun Dong Nam.

Eileen Goodman’s large-scale watercolors will be displayed to good advantage in the wide open spaces of Locks Gallery (600 Washington Square South), in the first of two major shows this season by artists named Goodman (the other, a Sidney Goodmanretrospective, opens in February at the Art Museum).

And try to catch two shows that opened last year but continue through January: Stuart Rome’s photographs of Indonesia at Snyderman (303 Cherry St.) and the fascinatingly unclassifiable mixed-media works of Jim Hinz at Larry Becker (43 N. 2nd St.),nicely teamed with Michael Scheiner’s glass constructions and David Wickland’s paintings.