The primary purpose of a frame on an oil or acrylic painting is to focus your attention on the work of art—to create a unified whole that stands alone, separate, and invites undisturbed contemplation. The primary purpose of a frame on a work on paper is to provide structure for the protection and presentation of the piece as well as to enhance its appearance. Learn what else you need to know about framing in this article from The Artist’s Magazine (June 2010), Rosemary Barrett Seidner.

The Fine Art of Framing

by Rosemary Barrett Seidner

Like the setting for a diamond, the frame around a work of art is the finishing touch, the element that completes and elevates a painting, presenting it to the viewer in its best possible light. Framing, however, is an art in and of itself, and just as a good frame choice can greatly enhance the appearance of a work, a poor frame choice can drastically diminish a work.

To Frame or Not To Frame

I’ll let you in on a secret: Not every work of art needs to be framed. For contemporary gallery-wrapped paintings, framing is completely optional. The term gallery wrap refers to canvas wrapped around thick stretcher bars and secured to the back rather than the sides of those bars. This mounting leaves the sides of the canvas smooth, neat and free of visible staples or tacks. Artists using this type of canvas mount often continue the painting around the sides or simply paint the sides a complementary neutral (See No-Frame Options A, below).

No-Frame Options, A

When a painting on canvas is not gallery-wrapped, the stretchers are thinner and the staples are visible along the sides. The obvious intent of the artist is that the piece will be framed, and the frame needs to have sufficient depth to accommodate the thickness of the canvas and stretchers.

Paintings on board or panel usually require the structure of framing for display, as do most paintings on paper. However, box mounting these works for sleek effect renders framing optional (See No-Frame Options B, below).

No-Frame Options, B

Which Frame?

There are several schools of thought with regard to frame selection—but no hard and fast rules. The preferred thinking is that the work of art, and nothing else, should direct the selection of the frame. Here are some guidelines:

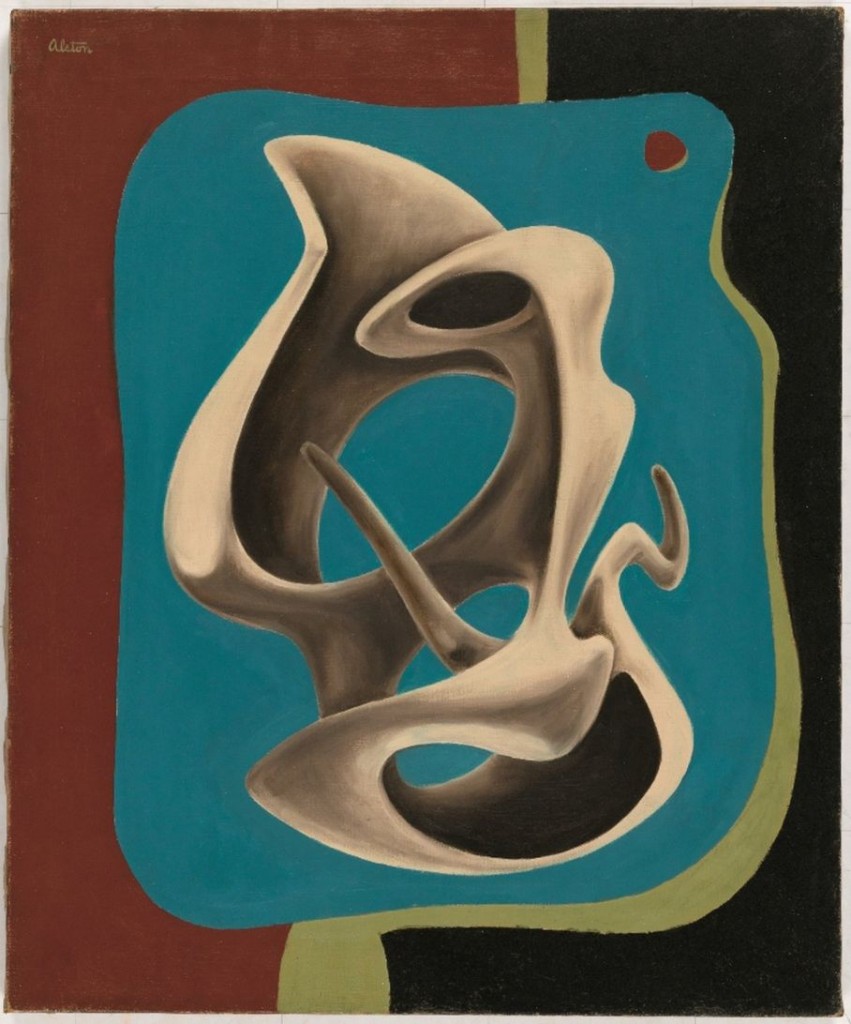

A painting’s style should suggest the frame style. For example, a period painting or one of classical subject matter is well suited to a timeless, traditional, elegant gold-leafed frame or a handsome walnut or mahogany wood frame. Lighter, ethereal, or more abstract paintings may look best in sleek, less fussy frames. And for paintings that are in-between, there are transitional frames—those that blend elements of the traditional and the contemporary. Be aware that each frame has a specific profile, clearly seen when viewing the diagonal cut on a frame sample.

Each work of art is its own universe. When the frame is selected to be of the greatest benefit to the art, the framed piece can be hung anywhere. A contemporary painting hanging in a traditional room doesn’t need to have a traditional frame; nor does a traditional painting in a contemporary room need a contemporary frame. And don’t fall into the trap of choosing a frame to match others you already have; some of the most stunning groupings of paintings feature pieces in a wide variety of frame styles, sizes and finishes.

Larger paintings usually look best with wider moldings and, therefore, larger frames. If, however, going big won’t work for you and your space, a floater frame may help. Floater frames usually add only 1 to 4 inches to the height and width of a large painting, whereas a regular frame of an appropriate size for a large work may add as much as 7 to 12 inches to the overall dimensions.

Depending on the style of the painting, your framer may recommend a multilayered frame composition—one or more frame moldings used together to achieve a unique look, with or without linen liner, plus fillet (image C, below). A frame and its linen liner should never be the same width. There are no rules stating which should be wider—although it’s often the frame.

Image C: Linen liners create visual breathing room between an

oil painting and its frame. A gold fillet adds a subdued decorative element.

Choose a frame finish that doesn’t compete with the art in color or texture. For example, don’t choose a fussy frame with a mottled finish to go with a busy image.

Always remember that framing has no hard and fast rules. Feel free to experiment! A nontraditional painting can look like a million dollars framed in a hefty, ornate and traditional molding, and a very small painting can take on new importance and become a special gem when placed in an oversized frame (image D, below). Here’s where the advice of a professional framer is especially helpful.

Image D: Placing the work ‘A Perfect 10′ (acrylic, 3×33/4) by Robert Anderson in an ornate, oversize frame goes against convention, but the striking result suggests a jewel in an antiqued gold setting.

Pointers for Works on Paper

Works on paper—watercolors, pastels, charcoal drawings and so forth—entail a special set of considerations because of the perishable quality of their surfaces.

Prior to framing, the work must be mounted on a support. Conservation mounting is strongly recommended. This means that at any time in the future you would be able to remove your artwork from the framing structure without causing any damage. Also, there would be no telltale signs that the work had ever been framed before. Conservation mounting is imperative for works of value or anticipated future value.

Acid-free corner pockets and acid-free adhesives are two good methods of securing artwork to its support. As for the support itself, archival foam board creates a sturdy structure for a framed piece on paper and helps protect artwork from pollutants that might find their way through the back of a framed piece.

In addition, most works on paper require matting and framing under glass for protection (see Glass Options, below). The matboard, with a cutout window, is laid over the painting and prevents the glass from touching the surface of the artwork. A spacer can be used in place of a mat. Matting also contributes to the presentation of the artwork (see Matting Aesthetics, below).

It‘s essential that all materials used be 100 percent acid-free. You may look back at pieces framed many years ago and see that the matting has discolored, as has the paper of the actual artwork where it came in contact with the matboard. This discoloration (acid burn), is caused by acid in cardboard backing, non-acid-free matting, acidic masking or Scotch tape. Many a fine work has been devalued in this way. All good framers now use acid-free or archival materials.

For Best Results

Many collectors and artists have an eye for selecting the right frame and can make sound decisions with little guidance from a professional. Quality framing, however, can be an expensive endeavor, so for most people the experienced advice of a professional is invaluable. In either case, don’t underestimate the importance of framing your artwork in the most suitable and visually attractive way. Take the time to make the right selections, and your artwork will bring pleasure for generations.

Glass Options

First and foremost, glass protects works on paper from dust and other pollutants, but it can also serve other important functions:

- Regular glass is the type most commonly used. It’s scratch-resistant but breaks easily in transportation and only filters out about half of the damaging ultraviolet (UV) light rays.

- Nonglare glass works well on pieces placed directly in front of a window. The drawback is that this glass tends to soften the image and give a slightly fuzzy appearance to the work. It also gives low UV protection.

- Conservation glazing is a coating applied to glass that offers 97 percent UV protection.

- Museum Glass is the ultimate—so clear and glare-free that you can’t see it at all when you stand in front of a painting. It also provides the best UV protection. This glass is expensive, but worth the price.

- Acrylic glazing, also known by the trade name Plexiglas, is much lighter than glass, which makes it a good alternative for large works of art. It’s virtually shatter proof, although it scratches easily. Available in regular and nonglare forms, acrylic provides about 60 percent UV protection. Regular glass cleaners may leave the surface looking foggy.

Matting Aesthetics

MORE RESOURCES FOR ARTISTS

• Watch art workshops on demand at ArtistsNetwork.TV

• Get unlimited access to over 100 art instruction ebooks

• Online seminars for fine artists

• Instantly download fine art magazines, books, videos & more

• Sign up for your Artist’s Network email newsletter & receive a FREE ebook

– See more at: http://www.artistsnetwork.com/articles/art-demos-techniques/how-to-choose-the-best-frame-to-present-and-protect-your-artwork?lid=CHtamar090112#sthash.SDVPj4EF.dpuf

No-Frame Options, A

No-Frame Options, A

No-Frame Options, B

No-Frame Options, B

Image C: Linen liners create visual breathing room between an

Image C: Linen liners create visual breathing room between an  Image D: Placing the work ‘A Perfect 10′ (acrylic, 3×33/4) by Robert Anderson in an ornate, oversize frame goes against convention, but the striking result suggests a jewel in an antiqued gold setting.

Image D: Placing the work ‘A Perfect 10′ (acrylic, 3×33/4) by Robert Anderson in an ornate, oversize frame goes against convention, but the striking result suggests a jewel in an antiqued gold setting.

Image E: Double matting is one way of introducing a thin strip of color.

Image E: Double matting is one way of introducing a thin strip of color.

Image F: For good visual balance, the mat (or linen liner) and frame should be different widths, and the mat should be weighted. The weighting can be subtle, as it is for ‘Look of Promise’ (acrylic, 20×24) by Ober-Rae Starr Livingstone. In this case the mat width measures 3¼ inches on the top and sides and 4 inches on the bottom. The gold fillet adds a thin strip of color.

Image F: For good visual balance, the mat (or linen liner) and frame should be different widths, and the mat should be weighted. The weighting can be subtle, as it is for ‘Look of Promise’ (acrylic, 20×24) by Ober-Rae Starr Livingstone. In this case the mat width measures 3¼ inches on the top and sides and 4 inches on the bottom. The gold fillet adds a thin strip of color.