Book includes poetry by Jill Scott, Trapeta Mayson, Richard Medina, Stephanie Renee

and more. This book was published in 1995. A collectors item.

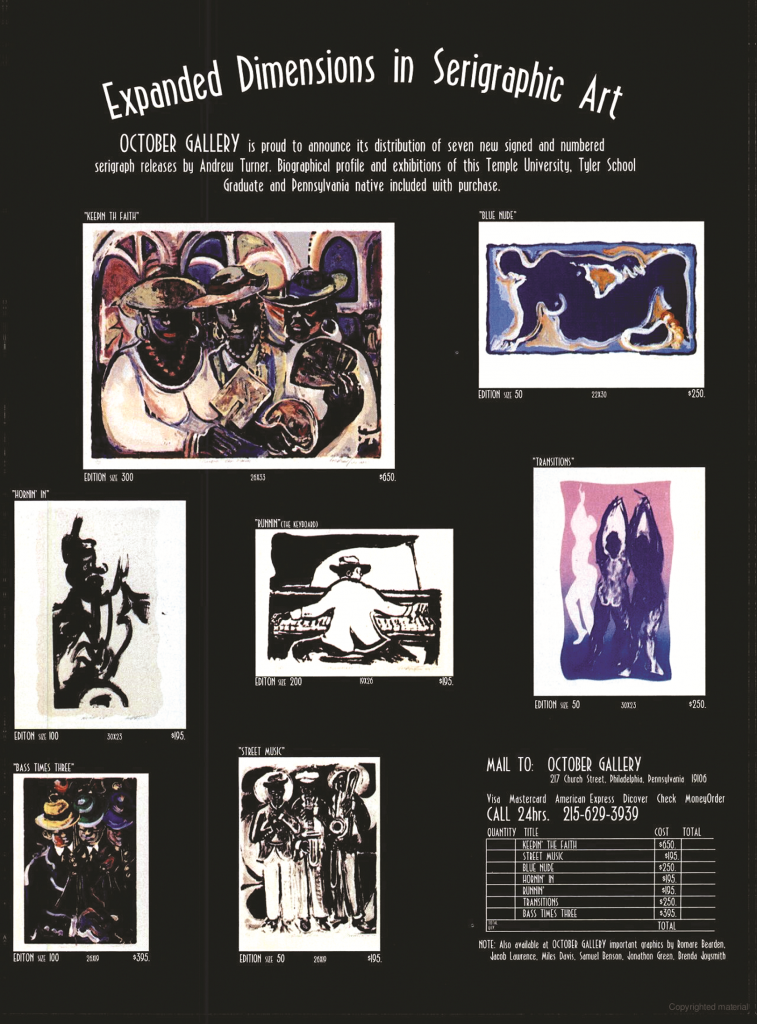

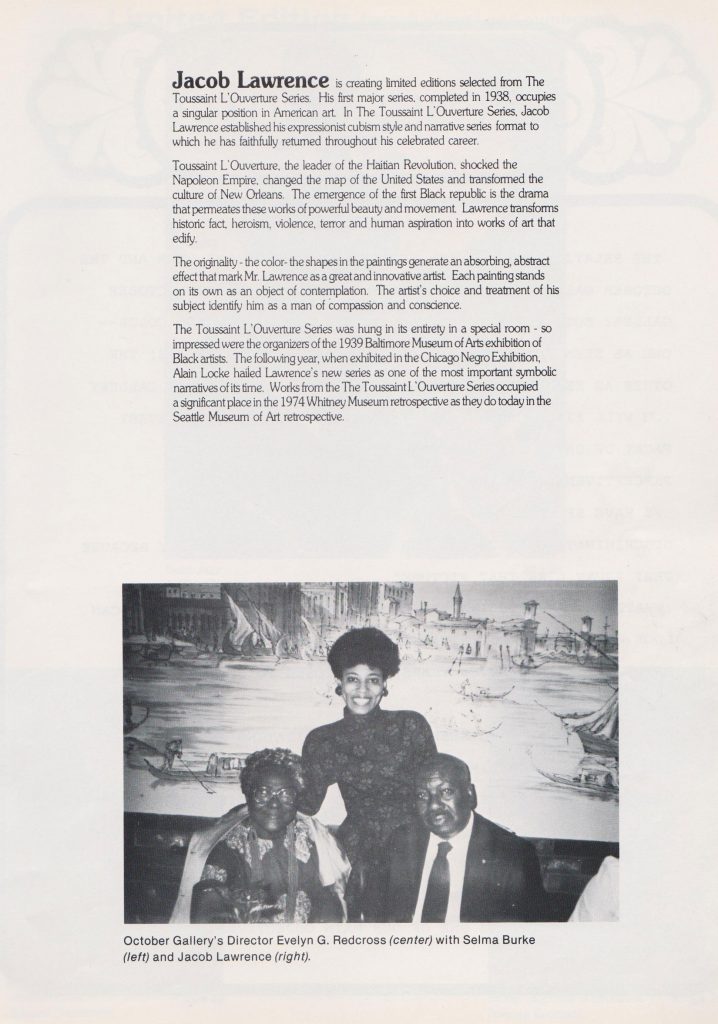

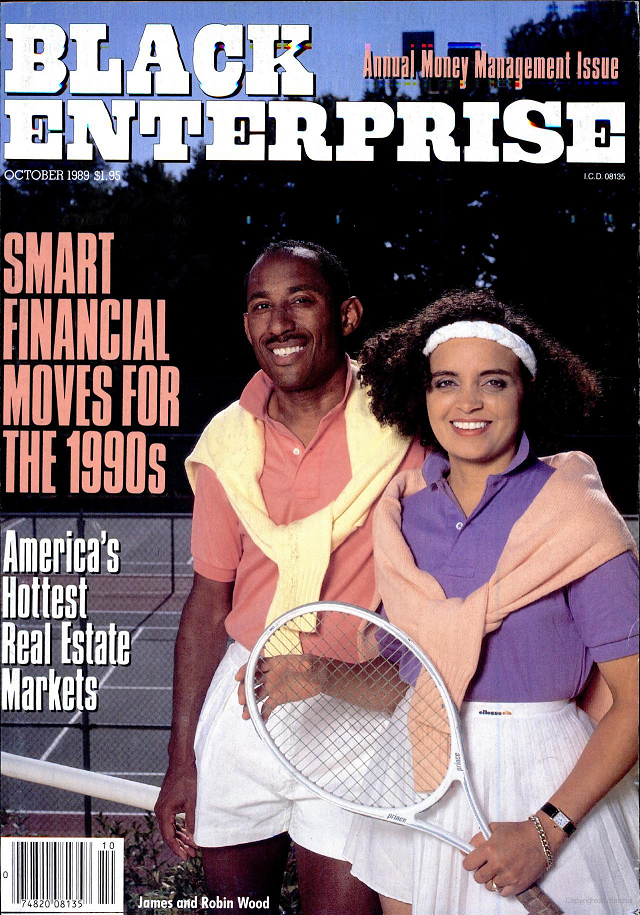

Black Enterprise Magazine Ad 1994 October Gallery Expo

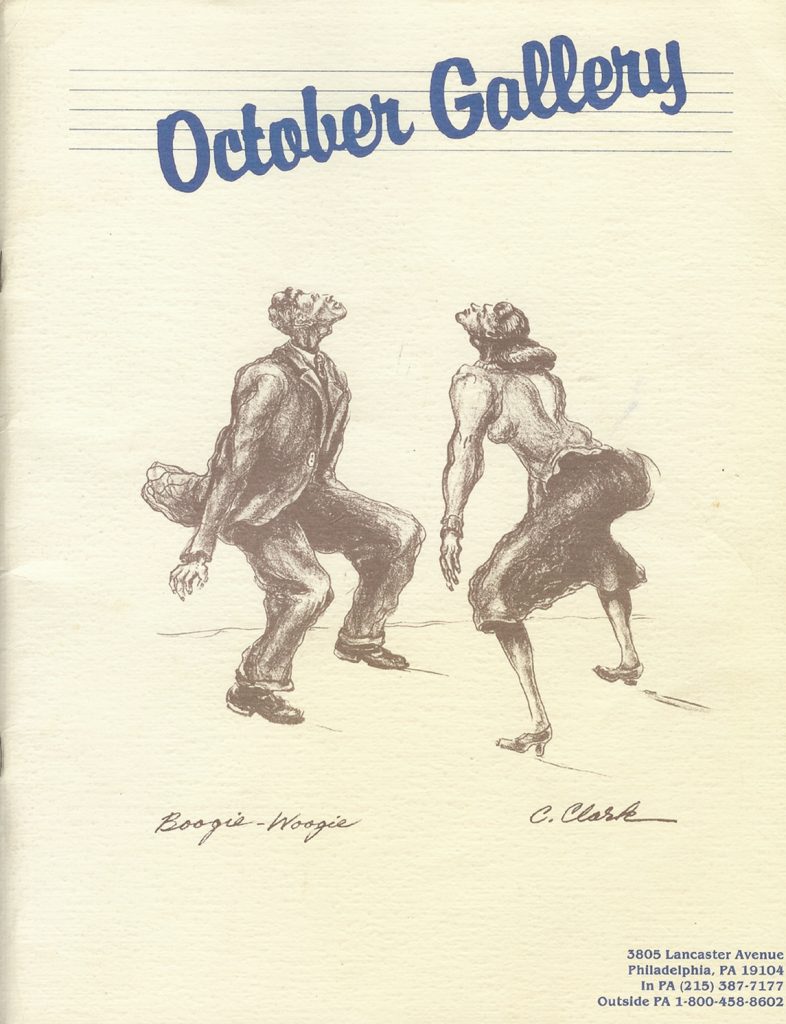

A Couple Who Showcase Black Americans’ Art The Galleries Of Mercer And Evelyn Redcross Grew Out Of Their Personal Quest.

Mercer and Evelyn Redcross share a dream and a vision.

You can see it on the walls of their two October Galleries, on the walls of their East Mount Airy home: vibrant artworks by African Americans.

“The October Gallery – or any gallery – is something you can point to, it has four walls. If you want to claim your culture, go there,” says Mercer, whose energy crackles, even over the phone.

Up the spiral staircase, in an office above their sunlit Powelton Village gallery, the couple speak together of their lives and work, closely intertwined for 24 years.

The gallery business came about almost by accident. Mercer is, by nature, the collector. Of trains. Of clocks. “And stained glass,” interjects Evelyn. ”You forget!”

They met and married while students at Fisk University in Nashville, then came to Mercer’s home town of Philadelphia in the late ’60s to complete their educations. He wound up with a job at the Federal Reserve Bank and she became a city social worker before they both took jobs at the same real estate office. Neither knew much about art.

But Mercer became intrigued with the splashy sports paintings of LeRoy Neiman and went to an auction of the artist’s works one day in a Philadelphia hotel. “I wanted to see them,” he says, then adds, “I wanted to own one.”

“Maybe we were just art collectors waiting to happen,” Mercer says.

So, the Redcrosses began acquiring art, first by known white artists like Neiman, Salvador Dali and Alexander Calder. But soon they began seeking work by African Americans and discovered there were few places to find it. Their quest became a treasure hunt that led them to artists working in obscurity, paintings unsold, sometimes 50 or 60 of them stacked in a basement.

These explorations “opened up a whole new world,” says Evelyn, a striking woman who on this day is wearing a bright red dress and large, ornamental earrings. “We decided that if we had trouble finding these works, others did too.”

She goes on. “African American artists needed a place to showplace their work. They couldn’t get shows (at existing galleries); that helped us establish a need.”

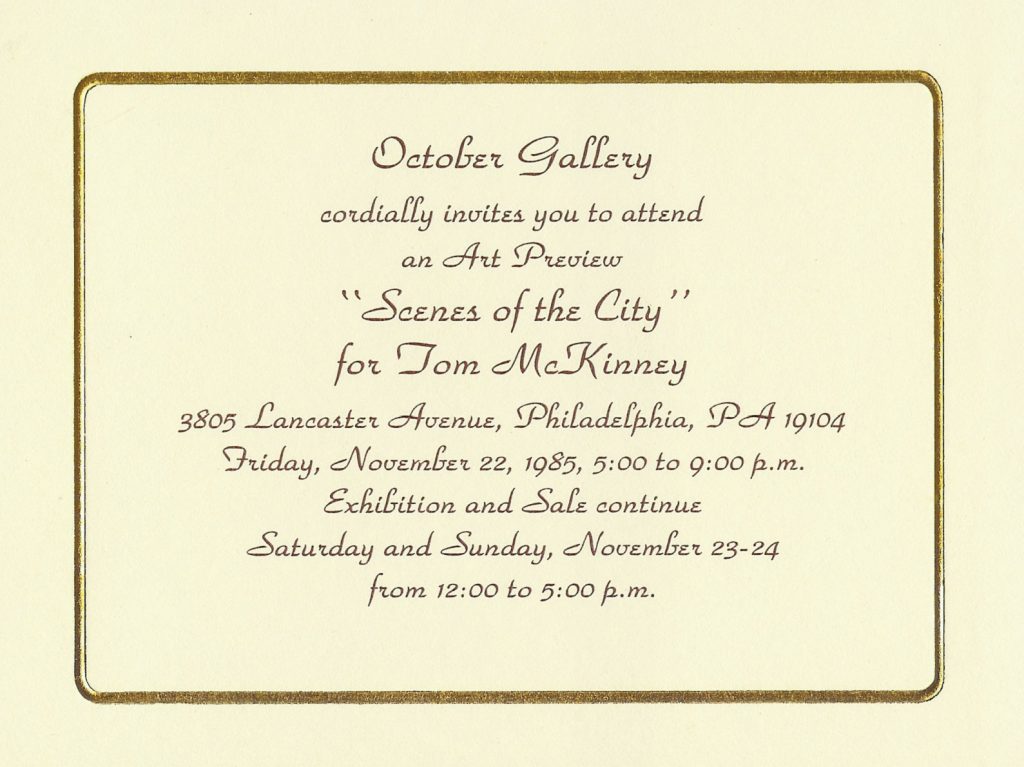

The Redcrosses opened the first October Gallery in a storefront on Lancaster Avenue in 1985. (The second is at the Gallery, 10th and Market Streets.)

“This is almost a natural extension of our relationship,” says Evelyn, who grew up in tiny Orangeburg, S.C. “We always did things together.”

“We are of one mind,” says her husband.

In the beginning, people flocked to the gallery. At least to look. “They were eager in terms of supporting us,” Mercer says, “but of committing and buying – that took longer.”

EDUCATING CONSUMERS

Mercer promoted relentlessly, trying to educate would-be buyers from the moment they entered the gallery. Many African Americans could afford the works, which range from $15 to $30,000 or more. Mercer’s job was to show them how the art was necessary to their lives, how it fit in.

“We know what a BMW will do for us, what a silk dress will do, what belonging to Little League will do,” he says.

Here was an American art form being expressed by African Americans. “Art that shares history and culture,” Evelyn explains.

When people saw the Redcrosses collecting this art themselves, they became curious. “If I’m willing to give up a $5,000 car for a piece of art, people want to know why,” says Mercer.

One reason was investment: Undervalued for years, some of the works purchased for maybe $500 at the beginning of the decade increased tenfold during the prosperous 1980s.

The Redcrosses mounted shows all over the country, in Washington, Chicago, Boston, California, even Utah. They found clients this way. They found more

artists this way. And artists found them, too.

Prominent people such as former Phillie Garry Maddox and rap musician Fresh Prince (who favors the athletic pieces of Ernie Barnes) began collecting art bought from the Redcrosses. Alvin Poussaint, Harvard professor and Cosby Show consultant, bought. Louis Sullivan, U.S. secretary of Health and Human Services, bought. Actress Cicely Tyson dropped in. Young Penn students brought their parents to the Powelton gallery.

REACHING OUT

In continuing to reach out to those who may not be exposed to art collections, the Redcrosses recently adopted the Andrew Hamilton public school at 57th and Spruce Streets. “We try to make what we have here available to the students,” Evelyn explains.

The advantages of their joint business and all-consuming cause are obvious. ”Two heads are better than one,” says Mercer. The downside: “When you get home, it’s hard to turn it off.”

Their three children, ages 22, 19 and 15, have always been involved with the galleries and have traveled with their parents from show to show. “My (15-year-old) daughter can handle a $10 sale or a $100,000 sale,” her father says.

As they’ve grown older, the children have contributed their opinions and recommendations. However, says Evelyn, “Sometimes they’re sick of hearing about the business.”

Often, Evelyn says, when she and her husband would hang a new work and talk about it, the children would act as if they were ignoring them. But when a guest would drop by, it would be the children who would tell the visitor all about the piece.

Their work, says Mercer, is “consuming, it takes everything. But we can’t forget the dream and the vision.” And, increasingly, “We have a lot of people who share the vision.”

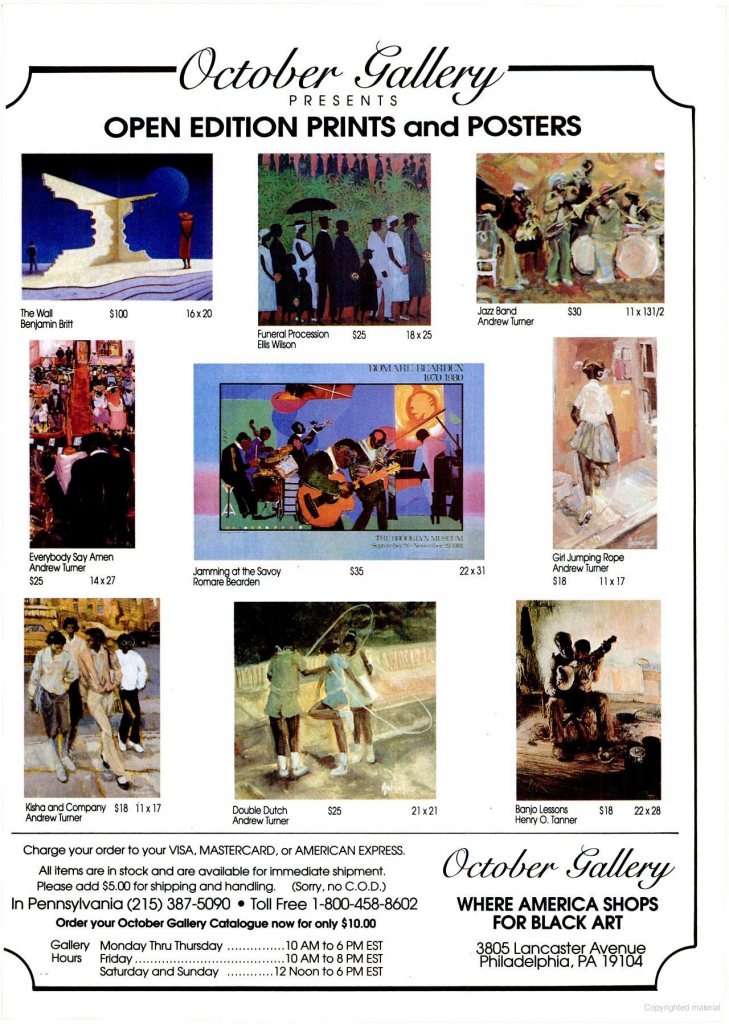

October Gallery’s First Catalog 1991. A Collectors Item.

In the Business of Giving – Philadelphia Inquirer 1991

October Gallery Ad in Black Enterprise Magazine 1989

Black Art Finds Its Own Space More Galleries Are Showing It, More People Are Buying It And Philadelphia Just Might Be Emerging As Its “National Mecca.”

Ten years ago, Germantown’s Lucien Crump, artist, educator and entrepreneur, could have communicated with all of Philadelphia’s black art- gallery owners by talking to a mirror.

These days, Crump has at least six competitors with galleries devoted to the work of black artists. Located in Old City, Powelton, Oak Lane, East Oak Lane, North Philadelphia and Germantown, their spaces hold the paintings, prints and sculptures of such internationally renowned artists as Jacob Lawrence and the late Romare Bearden, as well as established home-grown

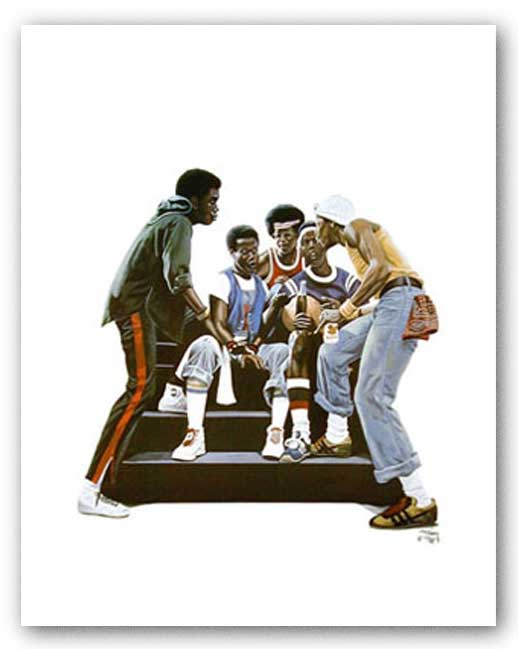

artists such as Tom McKinney, Ellen Powell Tiberino and Richard Watson. Sharing the walls are the works of Dane Tilghman, Andrew Turner, Dressler Smith and other emerging artists who have been hard pressed to find showcases.

The galleries brim not only with art once rarely seen, but also with new consumers eager to buy. These clients, predominantly black, range from working people with modest poster-and-print budgets to lawyers, physicians, politicians and other professionals who spend big bucks on original pieces. They are graduates fresh out of college, retirees and newlyweds who now believe it is more hip to start housekeeping with a Cal Massey print than a Cuisinart.

“Black people have always bought fine clothes and fine cars, rather than fine art,” said Crump, a painter for more than 40 years whose work is in many private and public collections. “People could always spend $30, $40 on a Saturday night. Now they are spending it on art.”

As Thomas Gunn of Laverock, Montgomery County, an international money broker, put it, his 125-piece collection is “fun. I just enjoy what I buy, and if it appreciates in value, that’s fine. But if not, I still enjoy it.”

In the city, the boom in black art centers on the Lucien Crump Art Gallery and the newer Chosen Image, Heritage, Mocha, Phoenix Rising, Crockett Atelier and October galleries. But it is not confined to Philadelphia. This decade has seen the creation of such thriving businesses as the Malcolm Brown Gallery in Shaker Heights, Ohio; the N’Namdi Gallery of Detroit; Isobel Neal Gallery in Chicago; Liz Harris Gallery in Boston; June Kelly in New York, and Sun Gallery in Washington.

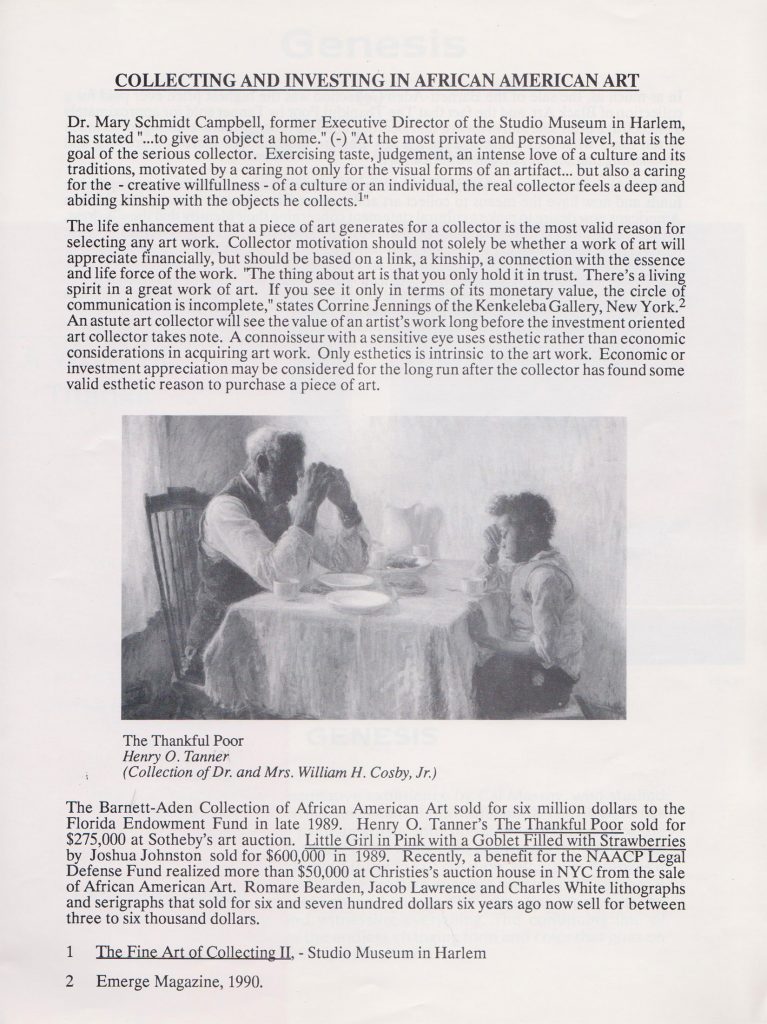

The phenomenon has grown under the media spotlight. Black Enterprise and Essence magazines have regularly published articles on the importance of supporting artists and the investment potential in art purchases. Bill Cosby’s TV home is filled with art by Brenda Joysmith and Ellis Wilson, among others; Cosby collects originals, such as fellow Philadelphian Henry Ossawa Tanner’s The Thankful Poor, which he purchased in 1981 for $250,000. At the time, it was a record price for a work by a black artist.

More significant, experts say, the burgeoning of black galleries has been a direct result of the art establishment’s systematic exclusion of artists of color, as documented in a report on New York galleries and museum exhibitions during the last seven years.

Compiled by Howardena Pindell, a Philadelphia-born artist and former associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art, the report found that as of mid-1988, 39 galleries – including nearly all of the most prestigious spaces – represented only white artists; only 10 galleries represented a selection of

artists that was less than 90 percent white, and one of those was in the process of closing.

This, Pindell wrote, in a state where 11,000 black, Asian, Hispanic and Native American artists live and work.

Counteracting that exclusion have been not only the galleries but also African arts festivals and, in some cities, a handful of pioneering museums.

Philadelphians’ interest has been piqued by the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, where there have been at least 100 shows and hundreds of thousands of visitors since it opened in 1976.

The museum’s role, executive director Rowena Stewart said, is “helping people become aware that within our community there is a core group of artists who are affordable and speak for us. Now it’s almost a no-no to walk into someone’s home and not see any Afro-American art. The trend is to have at least one piece, particularly if you are of Afro-American descent.”

Indeed, Mercer Redcross, who with his wife, Evelyn, owns the five-year-old October Gallery, 3805 Lancaster Ave. in Powelton, contended that Philadelphia was becoming “the national mecca for all kinds of black artists and black art” – for reasons as diverse as the mere presence of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a supportive city government and the magnetic pull of an already large and respected community of black artists.

There is no one black aesthetic, no single definitive quality that identifies an artist’s work as African-American, any more than there is for European, Asian or Caucasian art. And many black artists aim to broaden the term black art until it loses its stereotype – namely, representational images of urban bliss or misery and 1960s political protest art.

However, most new buyers of black art are seeking just that: realistic, figurative “work that reflects themselves and their experiences,” said Redcross. “People are hungry for something that reminds them of themselves.”

George Nock, a former New York Jets running back who grew up in North Philadelphia, can attest to that hunger.

Wildlife and fantasy were the primary inspirations for Nock, a Ben Franklin High School graduate who does pen-and-ink drawings, acrylics, watercolors and sculpture.

Since he began creating representational art inspired by black heritage about three years ago, he said, “I kept recalling the response. My sales had been about 50-50 wildlife and fantasy. Since then, 70 percent of my sales have been (figurative) African-American art.”

Nock’s one-man show at the Crump Gallery features 60 pieces of all these kinds of work. The show opened Saturday and will continue through Aug. 25 at the gallery, at Germantown Avenue and Johnson Street.

The gallery owners speak with an almost missionary zeal when they discuss their work. “We are experiencing an aesthetic growth that reflects our (African) heritage,” Crump said. “When it was time to plant crops, we used to put a piece of sculpture in the home; we used sculptured works in all recreational events, like weddings, harvests and so on.”

At Chosen Image, 6521 N. Broad St. in East Oak Lane, owner Sandra Broadus sees “a new awakening for our people. It’s growing every day and it’s important to educate and nurture our customers through this process, and make it possible for as many artists to share in this as possible.”

One early black-art advocate is white. For 20 years, Sande Webster of Sande Webster Gallery, 2018 Locust St., has sought to focus attention on artists whose work “continues to be stereotyped” and kept at the periphery of the art world.

Among Center City’s gallery owners, she said, she remains alone in her crusade.

Webster is voluble in her praise for the new black galleries, and is counting on them to quickly educate new buyers to appreciate more than figurative work.

Joe Tiberino, a white artist, has sponsored black-art showcases at Bacchanal, the South Street bar/restaurant he has co-owned for eight years, accepting just enough from sales to recover costs. Last year’s sculpture show of black cowboys by Phil Sumpter “went over very well,” he said.

“It’s not about profit for us.”

The galleries, needless to say, do not have that luxury. At the October Gallery, the Redcrosses envision glory days ahead. Recalling the 1970s’ golden era of the city’s music industry spearheaded by soul producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, Redcross said the couple aimed “to become the Gamble and Huff of the black art world.”

The Redcrosses, who founded the gallery in 1984, pioneered selling black art in hotels across the nation. They have an inventory in the thousands, they publish prints and they constantly promote their business, often by donating partial proceeds to such causes as the United Negro College Fund.

Ismail and Sharifa Abdul-Hamid, who own Heritage Gallery, 51 N. Third St. in Old City, have more modest goals. The gallery, which opened June 24, also carries Native American and Mexican-American art, and its current show, closing Sunday, combines both.

“The marketplace is barely scratched,” said Ismail Abdul-Hamid. “Our competition is not each other, it’s the video store, the record store, the gold jewelry. So people are beginning to buy seven albums instead of 10 and then buying the art.”

Another couple, Wanda and Terry Crockett of Crockett Atelier, plan to move their business from their Oak Lane home into a commercial space “within 18 months to two years,” said Wanda Crockett. “We’re specializing in finding and restoring to their rightful place older artists who couldn’t get into traditional galleries and literally threw their works in the basement.”

Lucien Crump, the acknowledged dean of the group, has competition right in Germantown, from Sameriah Allen of Mocha Gallery, 10-12 Church Lane. But, Allen said, “Lucien and I complement each other; he refers people to me, I sell prints of his work. We’re a lower-end gallery in price, we try to accommodate all budgets.”

Chosen Image’s Sandra Broadus founded her business because “people kept coming in wanting to buy my personal collection off the walls.” Her two-year- old gallery carries “50 percent traditional African scenes, 40 percent modern African-American art and only rare or unique abstracts and landscapes.”

Not all the stories are happy ones. Lucinda Johnson of Phoenix Rising, 2247 N. Broad St. in North Philadelphia, is struggling to recoup a $10,000 loss

from a burglary. She is re-establishing her business from her home, coping with the struggling artists she handles, serving private clients and working a full-time job with the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program. Like most of these owners, she said, “the bulk of my gallery income comes from the framing I do, so the break-in devastated me. But I really want to remain in North Philadelphia.”

With all her problems, Johnson remains committed to her field and to educating prospective buyers, such as Clarence Weaver, who browsed through Crump’s gallery recently.

Said the Philadelphia police officer, “It will be nice to have my history where I can look up and see it every day.”

Black Artists: Painted Into A Corner? Some Say Racism And Ignorance Still Limit Options In The Galleries

Barkley L. Hendricks remembers when he and other fellow artists, all prize- winning graduates of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, were hanging their paintings for the school’s final exhibition.

A professor at the school approached Hendricks’ work. “This is certainly a black wall,” the teacher told Hendricks. “Don’t you ever paint portraits of white people?”

Barkley is black.

The incident happened more than 20 years ago, but Hendricks contends that black artists continue to be victims of racism.

“It is one of the reasons that I left Philadelphia,” says Hendricks, who now lives in New London, Conn., where he paints and teaches art at Connecticut

College. “You find that this ignorance toward black artists continues in the galleries.”

Hendricks is one of many black artists who say they are discriminated against professionally because of their race. However, other minority artists contend they have never encountered racial prejudice in galleries; they say the role race plays in their art work has been overblown.

“Good art is good art,” notes Barbara Beatty, 48, a free-lance illustrator who paints landscapes with no black images and says she has encountered no prejudice from Philadelphia galleries. “A gallery owner looks at my slides and has no idea what color I am. This is simply not a problem.”

Ulrick Jean-Pierre, a Haitian artist who moved to Philadelphia 11 years ago, also contends gallery owners are colorblind. “They can relate to my work and its spiritual influences,” he says. “I can please myself and please everyone else.”

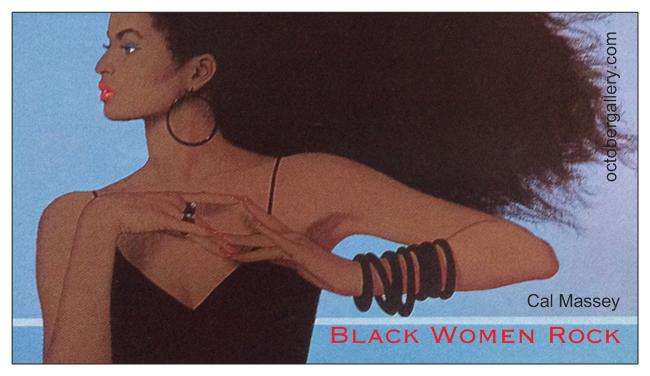

For others, the issue is not so simple. Cal Massey, a 63-year-old artist in Moorestown, N.J., who does portraits and drawings of black men and women, remembers when Art Expo – a huge annual exhibit of paintings and prints in New York – exhibited no black artists.

“No one thought they could sell black images,” says Massey. “No one thought blacks or whites would be interested . . . You have to blame galleries to a large degree for not exhibiting black art. For the assumption is made that blacks have no money and whites are not interested.”

“Black artists are not dealt with on the same level as white artists,” adds Hendricks, a nationally known realist painter whose work often focuses on young black people in urban settings. “And good black artists in this country are just not well known enough.”

For their part, gallery owners in Philadelphia contend there is no racism. ”I select my artists based on the slides I see,” says Benjamin Mangel of the Mangel Gallery in Rittenhouse Square. “Many times, I have no idea if the artist is black or white. You just want the art to be very good.

“I would like to exhibit more black artists,” adds Mangel, who has shown Hendricks’ paintings since 1980. “When I had a group showing of black

artists, I was accused of not showing any women artists.”

Like some artists, some art experts say the problem with gallery owners starts with education.

“Black art is not taught to future curators and critics in colleges. Only the latest edition of H.W. Janson’s standard text, ‘The History of Art,’ mentions a black artist. It’s not racism per se – it’s lack of familiarity,” says Liz Harris, who used to own two galleries in Boston and represents several black artists.

There are other issues to contend with when the topic of racism in the art world comes up. One concerns the subjects that black artists decide to paint.

“The notion of ‘black art’ is still confused. People think of it as political or protest art. That’s not all there is,” says Harris.

Some black artists are so reluctant to be categorized by race that they refuse to participate in shows like those tied to Black History Month, she says; she herself looks forward to the day when art won’t wear a racial label, ”when there will be just ‘art,’ period.”

“I don’t want to be viewed as an artist who paints the civil rights struggle,” adds Beatty, who is represented by a Washington, D.C., gallery. ”I am tired of hearing about it and would prefer to paint exactly what I want. That is the kind of freedom I enjoy.”

But can black art sell? And if it can’t, is that the reason why it is often rejected by some galleries?

Many gallery owners and artists believe that customers demand broad themes, that a painting of a ghetto scene will not appeal to everyone.

“Obviously, even a warm painting of a black family with black babies is not going to sit in a white family’s living room,” says John McDaniel, an abstract painter and exhibition coordinator at the Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum.

Others say that the marketability issue is simply a smoke screen for discrimination.

“It all depends on the policy of the gallery owner,” says Massey. “If the gallery owner is prejudiced, then you’ll see no black artists exhibited. Good art will sell if it is shown. There are black and white customers out there who are interested in this kind of work.”

“Very often, as in many disciplines, the subject is misunderstood,” says Evelyn Redcross, who along with her husband, Mercer, runs the October Gallery at 3805 Lancaster Ave. in Powelton Village. “Some of the galleries don’t respond to black art because they don’t understand it, or they refuse to open their minds to what black artists are doing.”

Redcross and her husband, who had been avid art collectors for the last 12 years, opened the October Gallery in 1985 to give exposure to black artists who were ignored by the big Center City galleries.

“There were people out there who demanded the art,” says Evelyn Redcross.

The Lucien Crump Art Gallery, at Germantown Avenue and Johnson Street in Germantown, also carries original art, posters and lithographs, mostly by black artists.

Crump, a painter and former junior high school art teacher, opened the neighborhood gallery seven years ago.

“When I decided to open, I wanted this gallery to be a service to the community,” Crump says. “If I made money, that was fine, but at the time, it wasn’t important.” Today Crump is thriving on a block where few stores selling more practical goods and merchandise succeed.

“My message to the American art family,” says Hendricks, “comes from the mouth of Hobson Pittman: ‘You are too good not to be better.’ ”

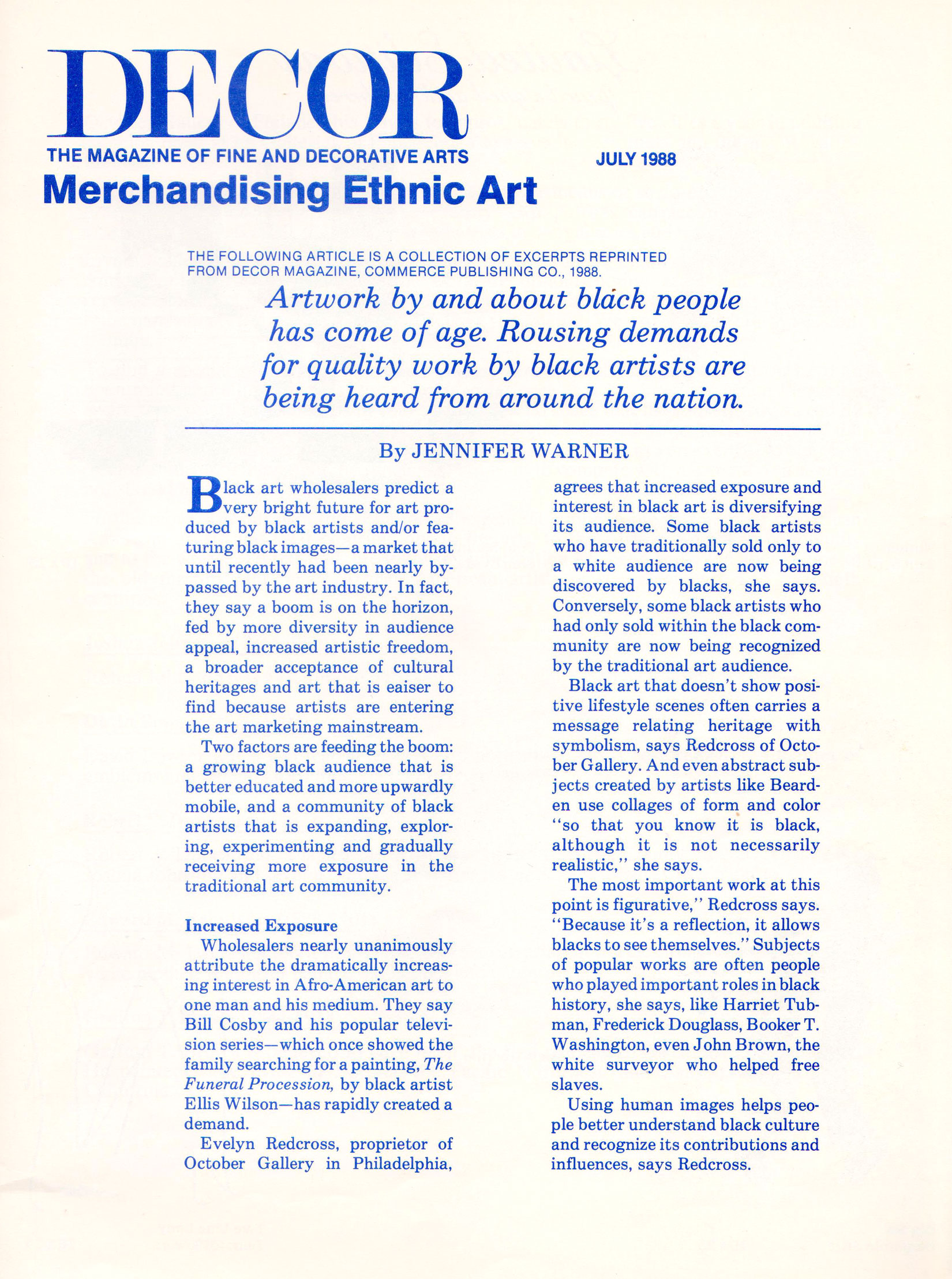

Decor Magazine 1988 – Merchandising Ethnic Art

Reviving The Work Of 2 Black Artists With Ties To The City

Black artists in America have been among the most invisible of Ralph Ellison’s “invisible men”; it has been only relatively recently that the best of them have received any meaningful recognition.

One is reminded of this poignant circumstance by the experience of two black artists who did achieve some degree of professional success, Dox Thrash and Claude Clark.

Both were natives of Georgia who settled in Philadelphia. Both managed to attend art school – Thrash before he came here, Clark after – and both were active in the local graphic arts workshop run by the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration during the 1930s.

Thrash, an innovative printmaker who developed a new intaglio process, died here in 1965 at the age of 73. Clark, born Nov. 11, 1915, is still active as a painter and teacher in Oakland, Calif.

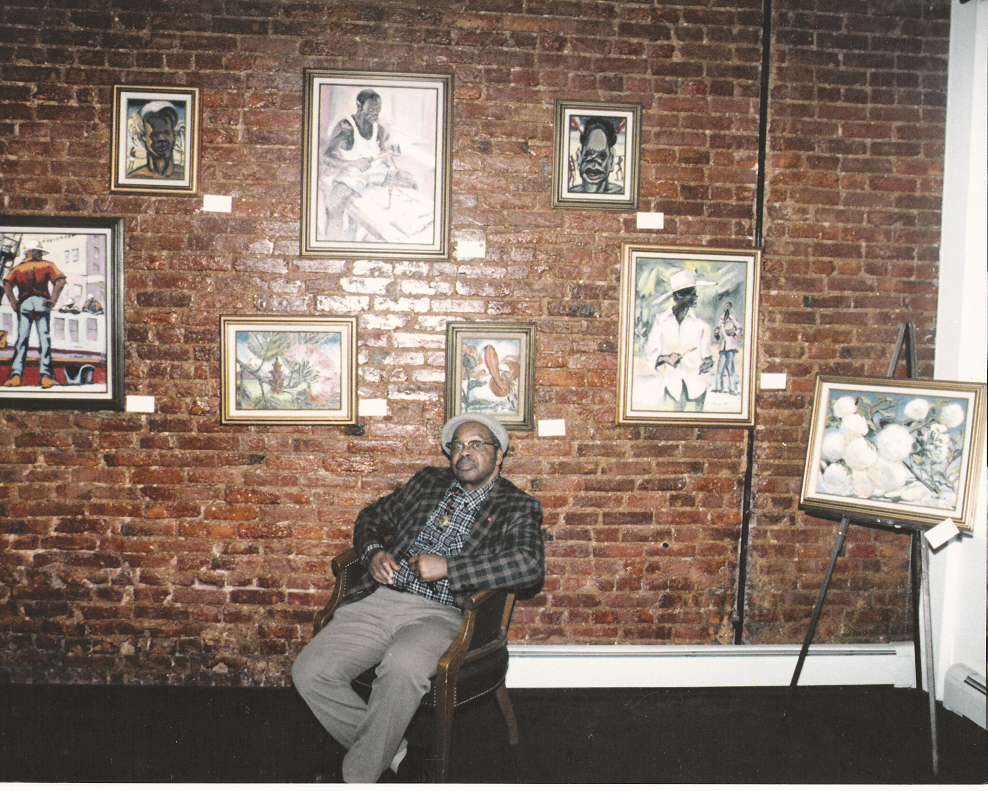

By coincidence, each has an exhibition in the city at the moment: Thrash at the Free Library of Philadelphia on Logan Square and Clark at the October Gallery, 3805 Lancaster Ave.

The Thrash exhibition, which will be up through May 29 in the library’s print and picture department, consists of more than 50 prints in various mediums and one watercolor-and-ink drawing. The Clark show, on view daily through March 15, is mainly oil paintings, with a few prints.

Although the exhibitions are quite different in many ways, they have common denominators of skill, determination and pride, both individual and communal. Each artist is, in his own way, a social realist. Each deals with black subject matter; Thrash’s is American, Clark’s more cosmopolitan in venturing into Africa and the Caribbean.

Neither is an artist of exceptional stylistic originality or visual perception – Thrash’s work, for example, is very similar to that of other social realists of 50 years ago. Yet each has created work that resonates with truth and humanity and, not incidentally, pride of heritage.

Thrash’s career is perhaps typical of many of his generation, black and white. It was characterized by years of scuffling and making do, of drifting

from city to city – as Thrash wrote in his memoirs, of “hobo-ing, working part time on odd jobs with the idea of observing, drawing and painting people of America. Especially the Negro.”

Thrash picked up some art training at the Art Institute of Chicago, both before and after World War I, during which he served in the Army.

He landed in Philadelphia after the war and decided to stay. He made his first prints under the tutelage of Earl Horter at the Graphic Sketch Club, later the Fleisher Art Memorial. In 1935 he hooked in with the fine-arts section of the WPA’s Federal Arts Program, which ran a workshop above Benny the Bum’s restaurant at 311 S. Broad St.

It was in the workshop that Thrash developed a graphic technique, an intaglio process called the carbograph, that would earn him modest fame. Two friends, Michael J. Gallagher and Hubert Mesibov, share credit with him for perfecting it.

Basically, Thrash discovered that a copper etching plate could be roughed up, or “grained,” by scrubbing it with crystals of silicon carbide, a very hard and sharp abrasive known commercially as Carborundum. After a plate had been so treated, a drawing could be transferred to it and an image created by working the roughened surface with tools.

When the plate was inked, the parts left rough would hold more ink and print dark; areas that had been smoothed or flattened with the tools would print lighter. It’s a process similar in concept to aquatint, and it’s still used by some artists today.

Thrash made a number of prints in the carbograph process, which produces a sculptural, tonal image rather than a linear one. He also made lithographs and etchings and some paintings.

In 1943, the WPA gave the Free Library a collection of about 70 prints that Thrash had made during the federal program. David King, head librarian in the print and picture department, has drawn the library’s show from this collection. He also included a section of carbographs made by some of Thrash’s contemporaries, including Gallagher and Mesibov.

The collection is primarily portraits, with some scenes from rural Georgia, some from urban Philadelphia and some of workers. The prints are undated but are believed to have been made between 1935 and 1942, when Thrash was involved with the WPA workshop.

Their taut composition style expresses the blunt, streetwise realism of the 1930s. The portraits are deceptively simple studies of Thrash’s friends, with unpretentious titles such as Linda, Ebony Joe and Charlott, but they are rendered with such quiet authority and dignity as to be almost iconic.

Thrash’s portrayals of workers display the typically muscular energy of Depression-era realism, but he could also be spirited and playful, as in a print of a man serenading a woman called Inveigling – the title conveys the mood precisely.

Thrash had a keen eye for street detail, displayed in an etching called Morley Court, and he could also appreciate the formal possibilities inherent in an ordinary group of houses, portrayed in a little gem of an aquatint called Suburbia.

He worked at a variety of jobs during his life, including railroad porter, steamship steward and house painter. He also said he had toured in vaudeville with a man named Whistling Rufus. His art never supported him, and when he died he was given only a brief and perfunctory obituary.

Thrash was one of many artists, kept afloat by the WPA during the Depression, whose art faded into obscurity after the project ended.

Claude Clark, on the other hand, was more fortunate – not only did he benefit from solid professional training, he has been able to earn a living teaching what he practices, although within the black community, and his paintings sell today at four-figure prices.

Clark moved with his family from Georgia to Philadelphia when he was 7, attended Roxborough Junior-Senior High School and won a four-year scholarship to Philadelphia College of Art.

From PCA, where for lack of money to buy canvas he often painted on window shades, he went to the Barnes Foundation in Merion, where he studied for four years. Eventually he earned a bachelor’s degree at Sacramento (Calif.) State

College and a master’s in painting from the University of California at Berkeley.

Clark has been a professor of art at Talladega College, Alabama, and he has traveled widely through the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America and Africa.

His travels provided the subject material for the paintings he’s showing at October; they’re essentially what in the 19th century would have been called genre painting.

Clark paints in a vigorous but disciplined style, using a palette knife to create passages of broken color. It’s a very physical approach that’s accentuated by Clark’s high-key Caribbean palette of bright, energetic color suffused with clear, brilliant light.

His works, like Thrash’s, express black experience from a distinctly black point of view, but they do so within a broadly humanistic framework that doesn’t require the viewer to have access to that experience.

Clark is represented in the national traveling exhibition “Hidden Heritage: Afro-American Art 1800-1950.” When that show opens at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Aug. 20, we will be able to better understand how little of the black visual tradition we have been allowed to see, and how much we have to learn from it.

*

The Thrash exhibition is on view in the print and picture department of the Free Library on Logan Square (686-5451) Monday through Friday from 9 to 5. Hours at October Gallery (387-5090) are Monday through Thursday 10 to 6, Friday 10 to 8 and Saturday and Sunday noon to 6.

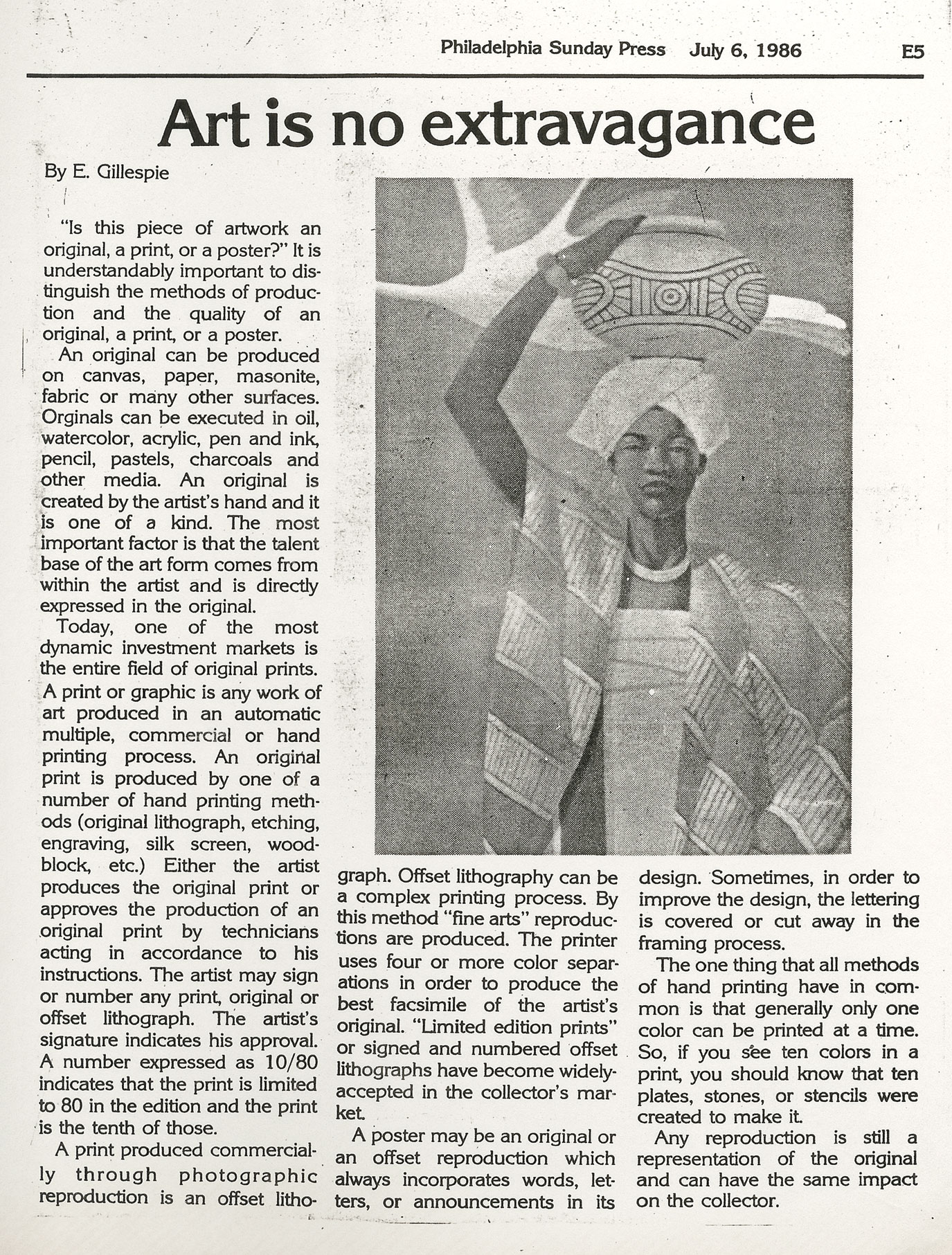

Art is no Extravagance Published Sunday Sun 1986

From A Quiet Still Life To An Action-packed Sports Scene

Among the current crop of solo exhibits around town, my highest praise goes to the young painter Scott Noel, featured at More Gallery Inc. He’s showing still lifes, paintings of nudes, domestic settings and pictures of recreational sports.

Fittingly, Noel’s still lifes are the show’s centerpiece. After all, still- life subjects traditionally have afforded painters the opportunity to display an unobtrusive mastery, so that portrayals of simple and familiar things become symbolic of wider experience. Noel’s still lifes can be awesome in their mastery, and they tend to have strongly integrated space.

Like many artists today, he opposes the depersonalization of still life. This is seen in his choice to paint humble objects casually strewn about his Chestnut Hill home and studio. In one instance, a half-eaten lunch on the artist’s drawing board is depicted gently and meticulously.

Noel’s nude subjects recall the everyday domestic interior views of turn- of-the-century French intimist painters. The male and female nudes are lethargic, yet supple.

Noel also shows affection for the rush and swirl of competitive sport. He has a good go at a basketball theme in pastel, and this suggests a promise that might be realized in his more finished figure work painted in oil.

More Gallery Inc., 1630 Walnut St. 735-1827. Monday-Saturday 10 a.m.-5:30 p.m., Wednesday to 7 p.m. Prices: $350 & up. Exhibit to June 11.

*

Ten years ago, Betty Augustine swapped her paints and brushes for scraps of fabric and her sewing machine. The result: color-rich, intricately patterned and quilted wall-hangings. These are featured in her display at Third Street Gallery.

Above all, this artist has a knack for asymmetrical harmonies. Her best work uses gridlike shapes – unsystematic ones – based on intuition instead of on any system. In this sparkling show, Augustine appears to have learned pointers about asymmetry from the renowned hard-edge abstract painting innovator Piet Mondrian.

Third Street Gallery, 626 S. Third St. 627-9169. Thursday & Sunday 1-6 p.m., Friday-Saturday 1-8 p.m. Prices: $75-$800. Exhibit to June 1.

In recent years, photographers have seemed more inclined to formulate philosophies about their work, isolate problems and debate the relative merits of certain ways of working. Evidence of this is seen in the existence locally of Phototaxis, an exclave of seven photographers who are joined together by a passionate involvement in photography.

Phototaxis’ current show at the Painted Bride ought to be seen as a significant, if modest, example of the process of meaningful interaction among photographers. Figure subjects by Jeanne Birdsall and Sarah van Keuren, and street-scene activity by Dennis Witmer and Anne Jackson are standouts.

Painted Bride Art Center, 230 Vine St. 925-9914. Monday-Friday 11 a.m.-6 p.m., Saturday 2-5 p.m. Prices: $150-$300. Exhibit to May 31.

The October Gallery in West Philadelphia has no ties to a neighborhood art center or to a university. And while it is small, it exudes energy and is bristling with work by black artists. Currently on display is a two-person painting show by Reba Dickerson Hill and Cal Massey on the first floor, and a diverse group on the second floor. Massey’s portrayal of hard-hat workers, more interesting than his abstract pictures here, evokes a Romanized noble ideal in a painting seemingly detached from emotion. Fresher, more emotive techniques mark Hill’s work.

October Gallery, 3805 Lancaster Ave. 387-5090. Thursday, Saturday & Sunday noon-5 p.m., Friday noon-8 p.m. Prices: $50 & up. Exhibit to May 31.

October Gallery’s first gallery art show and sale 1985. Artist Tom Mckinney.

Technology and Franchising

The proper use of technology can revolutionize the way you do business. With the right mix of technological tools and systems, your franchise can rise to the top of your business field and keep you t

Clown by Tom Mckinney

Clown by Tom Mckinney But Beautiful by Tom Mckinney

But Beautiful by Tom Mckinney

Tom Mckinney Exhibiting at Expo 15 – 2000

Tom Mckinney Exhibiting at Expo 15 – 2000